Thomas Partleton (c1732-1801)

Part 3

This page is a continuation of the story of Thomas Partleton . Click here to see Part 2.

In Parts 1 and 2 we learned that Thomas Partleton was married in London in 1759.

For 48 years, from 1759 to 1807, he and his wife Hannah and their children lived in the parish of St James Westminster, outlined in blue in John Cary's 1785 map of London below:

This London - Georgian London - where Thomas and his family lived between 1759 and 1801, was an extraordinary, colourful place.

Left: George II

Left: George II

This era is called Georgian because all the British kings before, during, and after our Thomas Partleton's lifetime were called George. Above we see George II, who had been born in Germany, who was king from the time our Thomas was born (c1732) till Thomas was about 28 years old.

In 1760 George II's son George III succeeded his dad, and was king for the whole of the remainder of Thomas Partleton's life. George III famously suffered from madness in his later life:

Left: George III

Left: George III

To give fair warning to the gentle reader, I'm going to go much deeper into events than I usually do in the pages of The Partleton Tree. The idea is to give us a feel for what it was like to walk around London in Thomas' shoes and to share his experiences.

-------

-------

Of course, those aren't Thomas' shoes, but they would have looked just like that. And Thomas would have worn a tricorn hat, at least some of the time: everyone did, as we shall see later in this story. So let's put on one of those too.

Thomas was literate; he could sign his own name at the very least, so we are going to read the newspapers with him, and go to the coffee house with him to discuss politics and worry about world events which were in a state of flux at the time.

Britain in the 1750s found itself in charge of what is sometimes flatteringly called its First Empire, and indeed was referred to in British newspapers at the time as 'the empire'. This "empire" consisted of some trading posts in Asia, a handful of Caribbean islands, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and thirteen American colonies, which, as we see them below, clung to a tiny percentage of the land mass of North America, stretching along its eastern coastline, competing for possession of North America with France and Spain:

As we learned earlier, Thomas Partleton was married in June 1759, a time when the Seven Years' War was at its peak. The colonies were not excluded from the war - indeed, on the contrary, they were one of the principal causes of the antagonism as the rivalry for colonisation of North America forced a life-or-death struggle with the French colonies to their west. The British and French - and Spanish - empires grappled for domination of the New World. The Seven Years' War can genuinely be accurately described the actual first world war - as it was fought in Europe, India, North America, the Caribbean, the Philippines and coastal Africa. Approximately one million people died.

This was a tense time for Londoners. During the months after Thomas' wedding, the newspapers were full of reports of the progress of the war in Europe which was being waged by Britain's ally Prussia - with the real and continuous threat of a French invasion of Britain. The papers were also brimming with delayed stories of events in America, where the Seven Years' War is sometimes known as the last of four French and Indian Wars.

The precarious nature of Britain's position can be seen in the map below. Britain's allies were small: Portugal and the state of Prussia. On the other side were the French Empire, The Spanish Empire, the Austrian Empire and the Russian Empire. Oh, and Sweden too. Frankly it looks like a losing proposition:

Let's remind ourselves of Thomas Partleton's wedding day; 02 June 1759:

At this time, the large-scale invasion plans of Britain by France were at the brink of fruition. Flat-bottomed invasion craft had been built in the Loire Valley, and an invasion force of 48,000 French troops were assembled near the coast, intended to be expanded to 100,000 during the actual invasion. Britain had no significant land-army to resist such an attack; serious defence of the island rested upon the navy.

In July 1759, Thomas would have been alarmed to learn that Britain's main ally, Prussia, had suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Kay, in what is now Poland. Extremely worrying.

The British were well aware of the French invasion plans - the newspapers were abuzz with the news of it. This is the Oxford Journal of Saturday 04 August 1759, with a morale-boosting - and dubious - report of French misfortune:

Left: Oxford Journal 04 August 1759

Left: Oxford Journal 04 August 1759

But this is the year known as the British Annus Mirabilis of 1759 - the year of miracles:

What we see above is a rendition of the Battle of Lagos which took place two months after Thomas Partleton's wedding, between parts of the British and French fleets on 19 August 1759 off the extreme southwest coast of Portugal, at the point of the purple arrow in the map below.

The French were defeated.

The French plan to invade Britain was carefully thought-out: the strategy would be to avoid a sea battle, slipping all the troops across the channel very quickly. The French navy wouldn't play much of a role in this undertaking. But the defeat of the navy at Lagos did give serious pause for thought; and it was a sufficient setback to the French to cause them to delay the invasion. The Annus Mirabilis had commenced.

Three weeks later, on 08 September 1759, Thomas Partleton was just settling in to his third month of married life. And he has some news for you: his wife Hannah is pregnant. Naturally Thomas would have been concerned about the state of the war.

He may have read in the newspapers that the British General James Wolfe had commenced a siege of the French colonial city of Quebec, at the point of the yellow arrow in the map below:

Such news from across the Atlantic took a month, sometimes two months, to reach the newspapers:

Left: Oxford Gazette 08 September 1759

Left: Oxford Gazette 08 September 1759

We know our Thomas was literate - he signed the Register of Marriages - so I'm going to declare that he followed events in the newspapers, and perhaps discussed the progress of the war with his friends.

Can I support that claim? Would a working-class man in London in the 1700s really follow the news in the papers?

To help us out with that, let's have a little dip into a small but fascinating autobiography, written by a Frenchman who lived in Georgian London:

The author, Antoine François Prévost d'Exiles, published the above book in 1742, having lived in exile in London for a while. Being an outsider, he took nothing for granted, and consequently his stories of London are full of fascinating detail, and are very interesting to us in the 21st century, since - to 18th-century London - we are also outsiders.

Monsieur Prévost was something of a character, so it's probably a good idea that we all have a look at him:

Left: Antoine François Prévost d'Exiles

Here's what Antoine tells us about the habits, attitudes and behaviour of ordinary Englishmen like our Thomas, and the options available to Thomas if he enjoyed keeping up with the news:

According to Antoine, 'The eagerness of the English for all such news is more than can be imagined... there is scarce a taylor who does not lay out two pence every day to satisfy his curiosity'.

Thanks to the British Library online archive I've been reading those 18th-century papers myself, and I can confirm that they are indeed full of all the things described by Monsieur Prévost, quack remedies, social scandal, items for sale, international intelligence, reflecting an apparently voracious appetite for any kind of news in their readers.

Prévost talks about coffee-houses, where news was read and exchanged, and according to him, patronised by rich and poor cheek-by-jowl. These sociable establishments experienced an explosive growth in popularity in the 1700s. Had Thomas visited them?... Let's put it this way: have you ever been in a Starbucks?

Coffee-houses abounded in and around Piccadilly where Thomas lived. Here's the Bath Chronicle on Thursday 12 March 1772

Left: Bath Chronicle, Thursday 12 March 1772

Left: Bath Chronicle, Thursday 12 March 1772

The location of Henry Buckle's coffee house, opposite Air Street, is outlined in blue in Rocque's gorgeous 1746 map of London:

And from the viewpoint of the red arrow, we see Air Street (at the left) on Piccadilly in 2011 courtesy of Google Street View:

Of course this is nothing like how it looked when Thomas Partleton resided in the area. The city block in view was built in the 1920s.

There's no coffee shop at the exact location of Buckle's on Piccadilly today. The present occupiers of that valuable piece of real estate are the NatWest bank in a 20th-century building. But on the north side of the road, as we see in the image of Air Street above, there is a Starbucks.

"Why are we talking about Starbucks?" I hear you say, and it's a fair question, and I'll come to my point in just a second.

Unsurprisingly, there are presently three Starbucks on Piccadilly [in 2012], including the one near Air Street, circled in red:

The map above, from their online store-locator, shows the site of the nearest fifty Starbucks to Piccadilly.

Fifty is quite a lot. Let's compare that with the popularity of coffee-houses in the 1700s:

The above clipping comes from A History and Survey of London published in 1739 by William Maitland.

551 coffee-houses, in a London which was just a fraction of its modern size; that's also quite a lot.

Of course, there were also thousands of pubs to frequent if Thomas liked a drink. And below we see another popular sociable venue; the tobacconist's:

The above engraving of LaCroix' congenial-looking parlour may be an early work by William Hogarth who, in his youth, earned money as an artist for advertising. We'll see more of William's work later as he will help us visualise London as Thomas Partleton saw it.

Of note in the picture above is that all of the men are wearing tricorn hats - an indispensable part of a man's wardrobe for the whole of the 18th century. If Thomas never wore one, I'll eat my hat, though I should add in all fairness that I don't possess one. Never liked them.

I've chosen that picture of LaCroix' establishment because of its address: 'Warwick Street, near Swallow Street'. Thomas Partleton lived for years on Swallow Street, though the tobacconist's advert is of an earlier date. Thomas' house on Swallow Street is outlined in yellow; Warwick Street, a few yards away, circled in green:

All of that diversion into coffee-houses and newspapers was merely to make the point that ordinary Englishmen like Thomas had an appetite for politics and for news.

Let's put Thomas Partleton in September 1759 in a coffee house, reading, in a newspaper, about events which had occurred two months earlier; that an attack and siege by the British on Quebec - the main French stronghold in North America - was being undertaken by General James Wolfe.

Quebec is at the point of the yellow arrow in the map below, the main city of the French-claimed area of North America, shaded in green, which was named New France:

News travelled very slowly. Here's the Derby Mercury of Friday 05 October 1759 again reporting events of fully two months earlier:

Left: Derby Mercury, Friday 05 October 1759

Left: Derby Mercury, Friday 05 October 1759

The Derby Mercury confidently anticipated a successful outcome, which would put Britain effectively in possession of all Canada.

However, the newspaper also knew that, although the siege of the citadel was nearly complete, the French army was still largely intact. They numbered 13,390 but included large numbers of irregulars. The British force totalled about 7000. A dangerous pitched battle between these two land forces at Quebec was imminent, indeed - at the time of publication - had probably already taken place. But tantalisingly, the final result of the conflict was not known.

15 days later, the anxious wait for news was over. Thomas Partleton and the whole of Britain could celebrate:

Left: Oxford Journal, Saturday 20 October 1759

Left: Oxford Journal, Saturday 20 October 1759

To say that this battle was pivotal is an understatement. The British Annus Mirabilis of 1759 had continued, and the French were now facing defeat in all theatres of war. The world as we know it, with the small country that was Britain playing a major part, was being shaped.

The battle at Quebec is now known as the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. General Wolfe was wounded and died on the battlefield, as depicted some years later by artist Benjamin West:

The Oxford Journal had printed a special edition to celebrate the victory, apologising to its advertisers for deferring their adverts. Below we see a description of typical celebrations across Britain which Thomas would have witnessed. Thomas and Hannah may have joined in.

Left: Oxford Journal, Saturday 20 October 1759

Left: Oxford Journal, Saturday 20 October 1759

All of these celebrations in Britain were completely premature. Yes, the British were now in possession of the citadel of Quebec, but the British navy had to withdraw soon after, as the St Lawrence River froze, leaving the British soldiers in Quebec to their own devices to face a Canadian winter.

The British garrison experienced a terrible winter, with many dying of scurvy, and soon numbered only 4000. The large remainder of the French army, 7000 men, which had withdrawn to lick its wounds, returned to Quebec, and now it was the British who were under siege. If the French navy returned with reinforcements, they would surely re-take Quebec.

But in November 1759, the British and French fleets met again, off the coast of France, at the Battle of Quiberon Bay, painted by artist Richard Wright the following year:

British Admiral Sir Edward Hawke had been maintaining a close blockade of French ports throughout 1759 with the objective of preventing the planned invasion of Britain.

Much of the invasion fleet of transports were gathered in the Loire Estuary, and though the main invasion of Britain was now too risky after the French defeat at Lagos, France still had a secondary scheme involving invasion via Scotland. The French fleet was ordered to break the blockade.

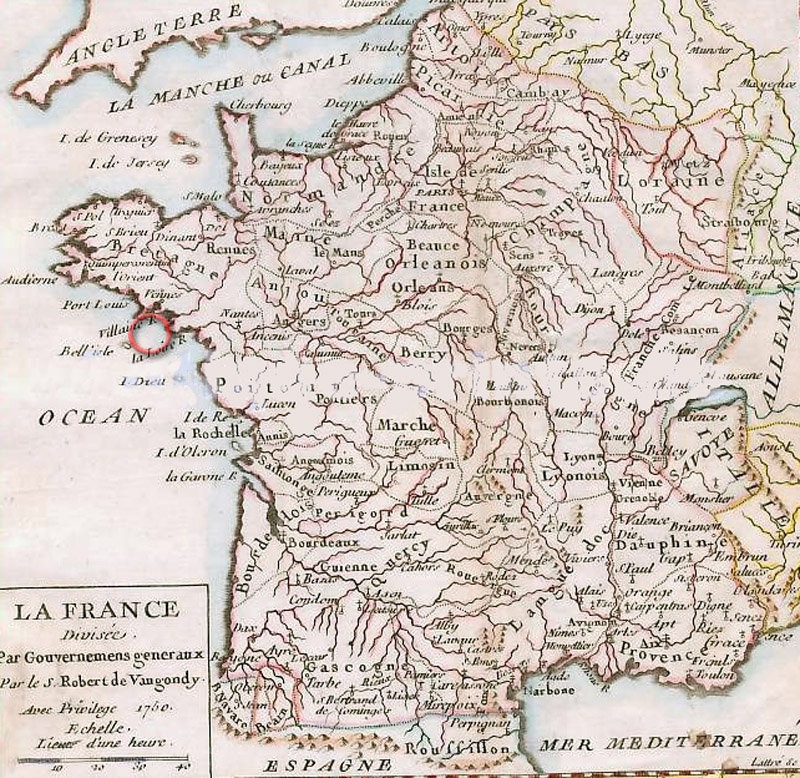

The location of the ensuing sea battle of Quiberon Bay is shown in the red circle in the French map of 1760 we see below:

The battle was disastrous for the French fleet, with many of their ships being driven on to the rocks, as vividly portrayed by Richard Wright in the painting above.

The British Annus Mirabilis of 1759 was now complete: the French fleet, after two major naval defeats, was so completely broken that the British now had a free hand across the oceans to move against French interests and colonies, and to strike against French commerce. The effect of this was so severe that France soon had to default on her debt.

And - if Thomas Partleton believed everything he read in the newspapers - there appeared to be more good news from Quebec, even though the 'news' was two months out of date:

Left: Oxford Journal, Saturday 08 December 1759

Left: Oxford Journal, Saturday 08 December 1759

When we read the above letter, we need to understand this: that its British author knew that it was to be published in the public domain and would surely be read by the French population and their political masters. Consequently the whole thing is piffle. It is purest propaganda.

The reality of the situation at Quebec was quite to the contrary; the British garrison did not have ten months' provisions, or anything like it - many soldiers became sick with scurvy over the winter; and there were many ill and injured, and there were nothing like 5000 of them. Above all, the French army in the field in Canada had absolutely no intention of surrendering.

Let's get back to our Thomas Partleton. I don't want to lose him amidst all these world events. We learned earlier that his wife was pregnant. As the year turned into 1760, on 25 January, Thomas' first child was born, named Hannah after her mum:

With their first baby at home, and the threat of a French invasion receding, this seems a good moment to break off to a new page, a new chapter in Thomas and Hannah's lives.

And it's such a long story, I'm going to continue it with the story of Thomas' daughter Hannah, but that is for another day.

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'In Their Shoes' Page.