Thomas Partleton (c1732-1801)

Part 2

This page is a continuation of the story of Thomas Partleton . Click here to see Part 1.

We know that Thomas Partleton was married in Westminster in the centre of London in the year 1759. But it seems there were no Partletons in London before that date. If he's roughly the same age as his wife Hannah, perhaps a smidge older, Thomas was born between 1732 and 1736. Where did he come from?

Well, there is one place, and one place only, where the name surname Partleton exists before it appears in London...

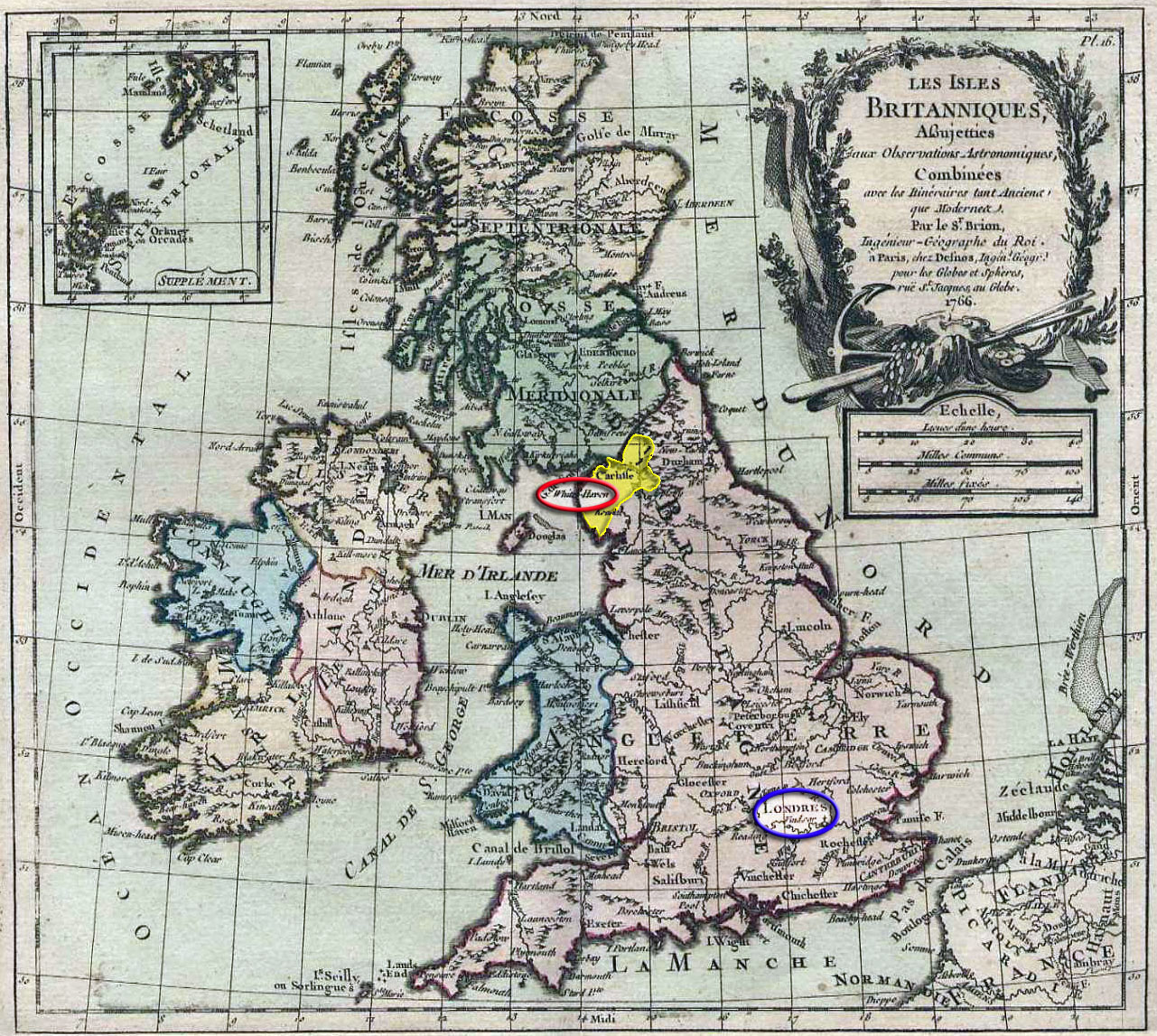

In the lovely, accurate, French map of the British Isles below, drawn in 1766 when Thomas Partleton had been married seven years, I have highlighted two places: London, circled in blue, we know about. The other place, highlighted in yellow, is the former county of Cumberland, on the Scottish border, and especially the port town of Whitehaven, circled red:

In the 1700s, the name Partleton only existed in London and Whitehaven... that's a peculiar combination, don't you agree?

Based on this, I'm going to make a case for Thomas Partleton coming to London from Whitehaven, and that's a piece of speculation. In this case I'm going to break my own rule of only sticking to supportable facts. But how would Thomas have done it? Check out that map. In the country of England, you can't get much further from London than Whitehaven without ending up in Scotland. In the 1700s this would have been a slow daunting journey along rough roads through the ruts and potholes: one which you wouldn't have made unless you had a very good reason.

A much more likely route would have been a sea voyage, and since Whitehaven is a seaport, and we know from other evidence that some of the Partletons who lived in Whitehaven were mariners, this is quite a supportable theory.

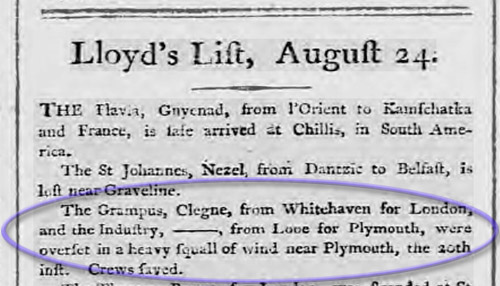

There were sailings from Whitehaven to London, as we see reported in the Caledonian Mercury on Monday 27 August 1792, when a ship was lost on this route:

Left: Caledonian Mercury, Monday 27 August 1792

Left: Caledonian Mercury, Monday 27 August 1792

So, let's join Thomas on his purely conjectural sea journey as he departs Whitehaven, drawn by William Daniell, with its coal mines in the distance...

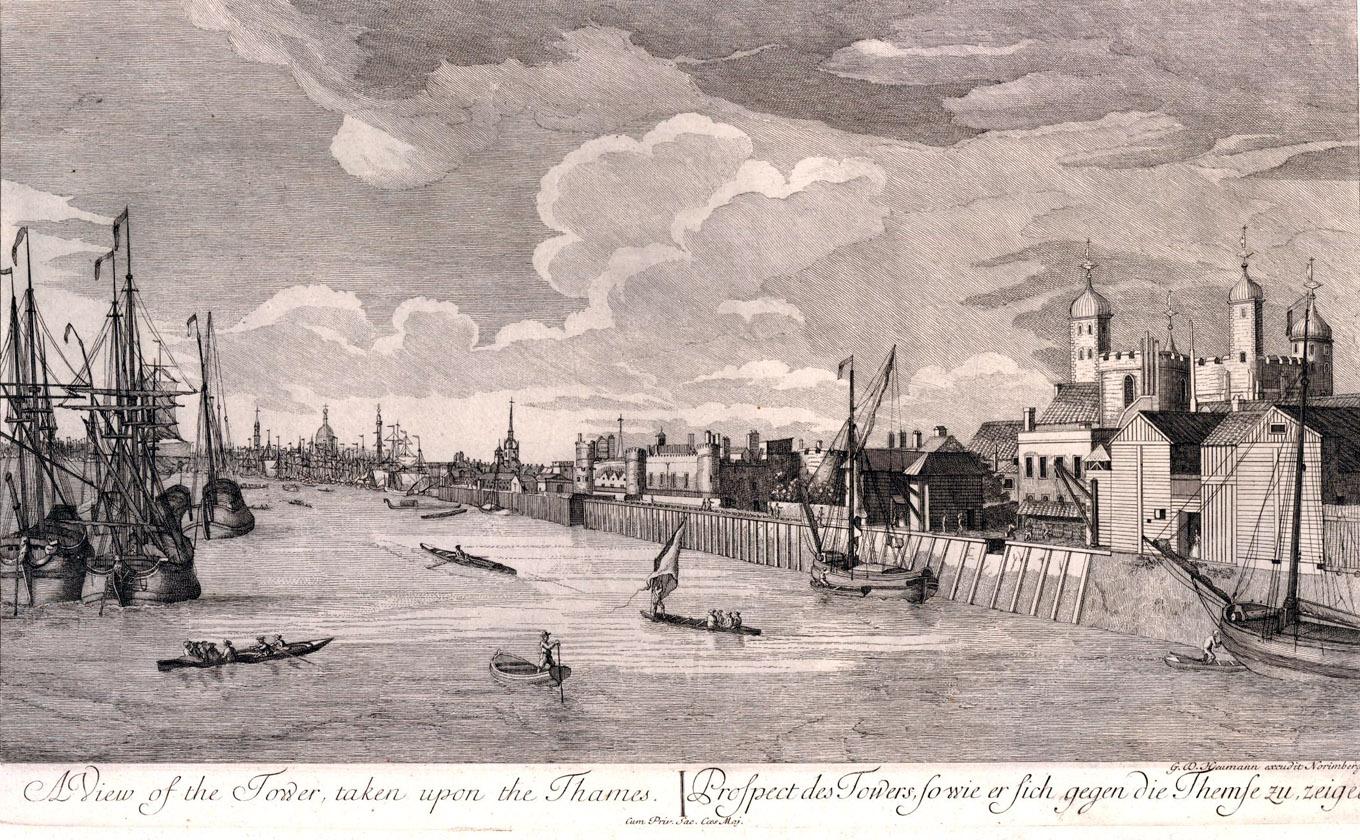

... and arrives in London for the first time in the 1750s:

The above was published by Georg Daniel Heumann approximately in the year 1750, so it's a very apt image for the period of our Thomas.

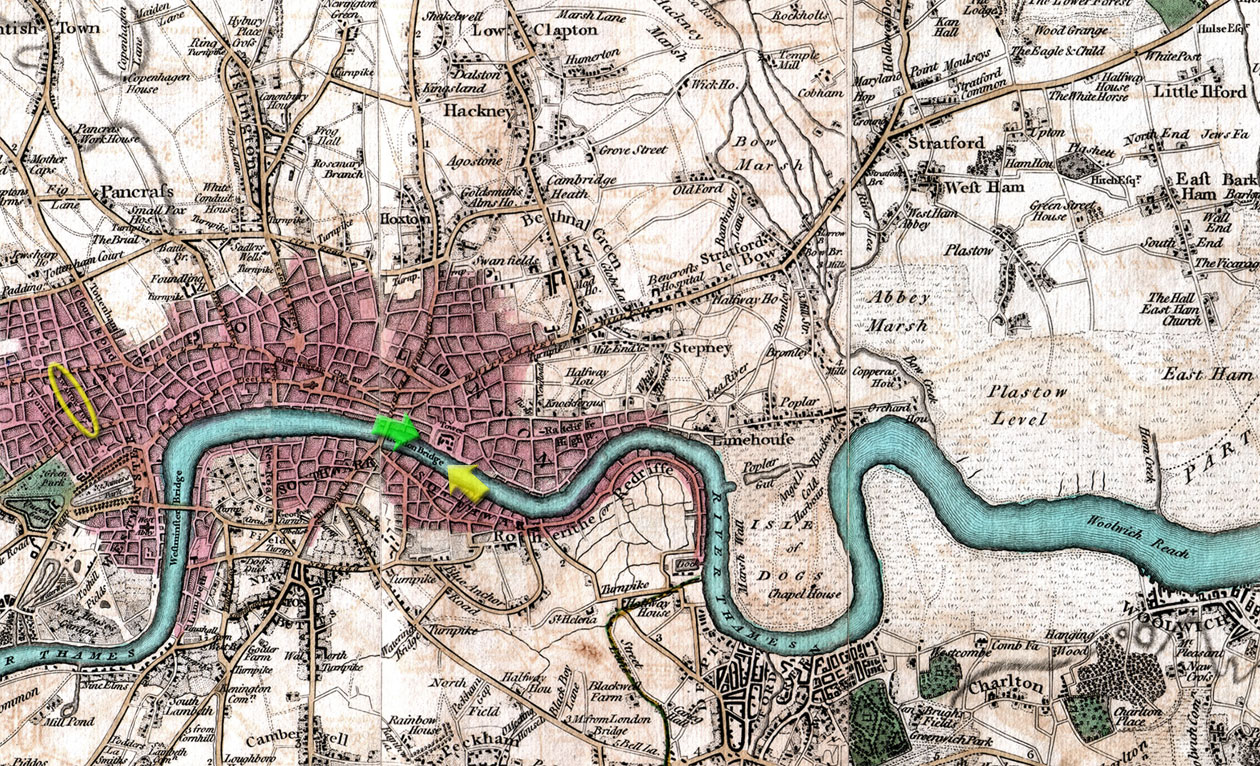

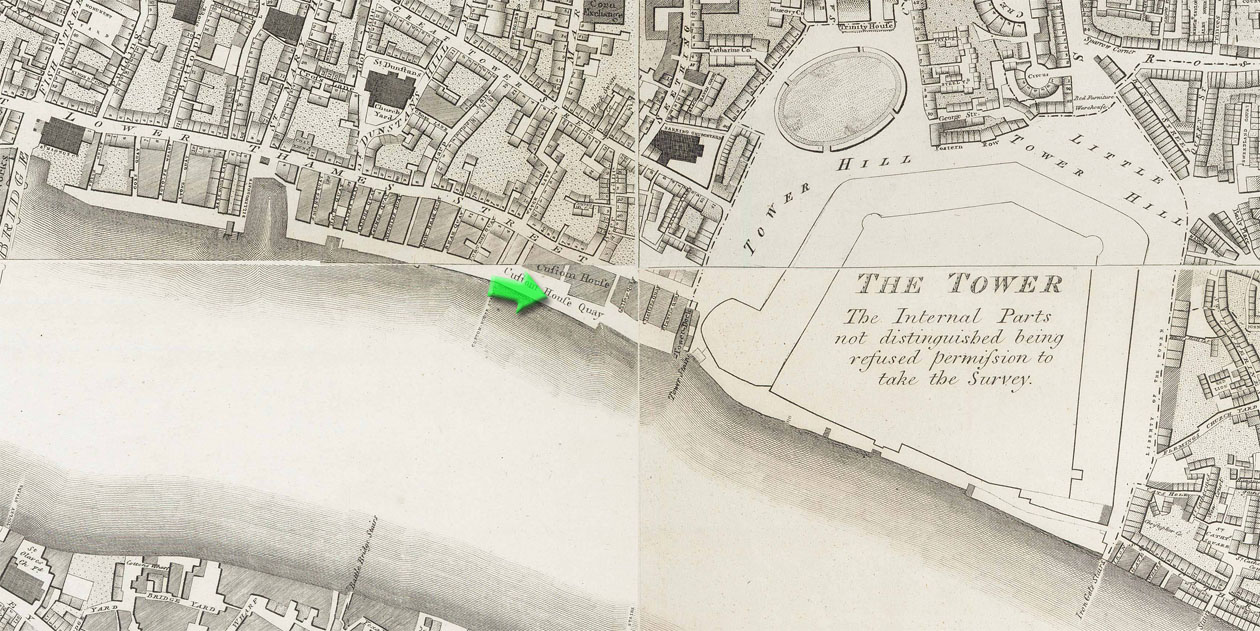

Heumann created his view of the Thames and the Tower of London, on the right, from a boat on the river at the point of the yellow arrow in John Cary's 1785 map below:

In the next engraving, seen from the viewpoint of the green arrow, we can visualise what it would be like to arrive at the great port of London in the 1750s. His ship would be amongst the hundreds of masts thronging at the quayside:

This engraving was created in 1757 by Frenchman and London-resident Louis Philippe Boitard. It is addressed to the many British Francophobes, with tongue in cheek reminding them of French imports such as fine wine, cheese, culture, fashion and style which were much sought-after and vigorously consumed in London. What is not obvious to us is that, in the year this engraving was drawn, and indeed also two years later in 1759 when Thomas Partleton was married, England was at war. With France, of course.

That particular conflict was The Seven Years' War (1756-1763). In the year 1759, when the war was at its peak, England was under a well-recognised, actual, and genuine threat of invasion by France.

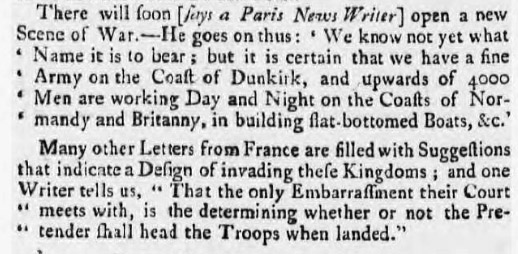

Thomas Partleton would certainly be aware of the rumours flying around London of impending French invasion. Here's Jackson's Oxford Journal, published on the very day Thomas was married, 02 June 1759:

Left: Oxford Journal, Saturday 02 June 1759

Left: Oxford Journal, Saturday 02 June 1759

Of interest here is the reference to the Pretender, a man so well-known that the Oxford Journal deemed it unnecessary to elaborate further on his identity other than to use his alias. This pretender to the throne was Charles Edward Stuart, aka Bonnie Prince Charlie, who was the pivot of the French plans to invade Britain.

Below we see Charles, in, what - I've got to say, oooh-er missus - is a bit of a phallic pose:

Charlie was the grandson of James II, the king who had been deposed and exiled from Britain in 1688 during the Glorious Revolution.

To hold the threat of invasion at bay, the English maintained a tight and successful blockade on major French ports throughout 1759 under the command of Admiral Edward Hawke. Consequently, one can be fairly certain that French cheese and wine, unobtainable due to the blockade, were definitely not served to Thomas Partleton's wedding guests.

Back to the fantastic engraving of the Port of London:

To create his picture, looking eastwards towards the Tower of London, Louis Boitard stood on Custom House Quay, at the point of the green arrow in Richard Horwood's 1799 map below:

Mapmaker Richard Horwood was a perfectionist. He drew - literally - every house in London, each at its exact location and scale and orientation. In the section of map above, Richard's irritation at being refused access is apparent in his terse notation within the Tower of London; 'The Internal Parts not distinguished being refused permiſsion to take the Survey'.

But I'm itching to terminate this page as quickly as possible: it's only speculation that Thomas came from Cumberland, and I'd like to get back to the facts, where we can all be more comfortable.

In the next part of Thomas Partleton's story, we are going to step into his shoes - which would have been quite similar the ones we see below - and take a walk around London in the 1700s exactly as he saw it:

Click here to proceed to Part 3 of the story of Thomas Partleton.

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'In Their Shoes' Page.