Sarah Partleton (1845-1849)

Drury Lane

Have you seen the muffin man?

The muffin man, the muffin man.

Have you seen the muffin man,

He lives down Drury Lane...

He lives down Drury Lane...

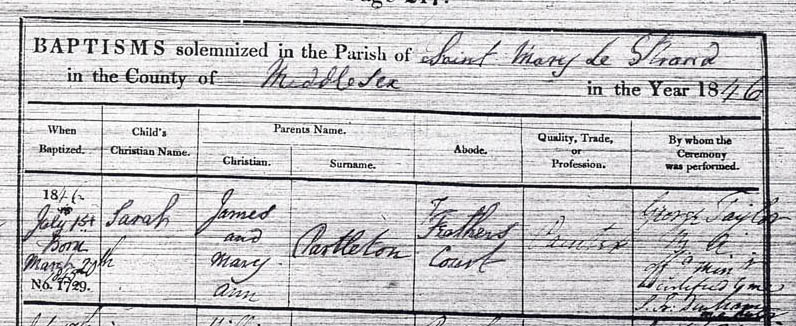

Sarah Partleton, daughter of James Partleton and Mary Ann Palmer, was born on 20 March 1845 at 7 Feathers Court, Drury Lane, in the vicinity of the The Strand in London. She lived only four years, so I think it's appropriate that this page is dedicated to that era of overpopulation and diseases and to the plight of innocents such as she in Victorian London:

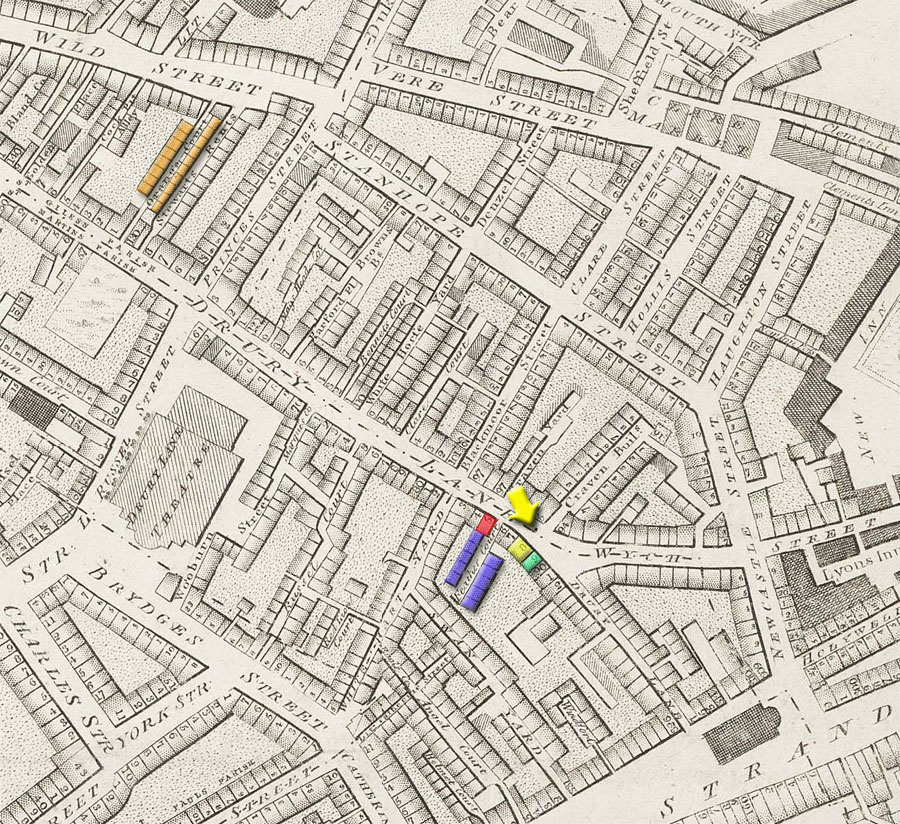

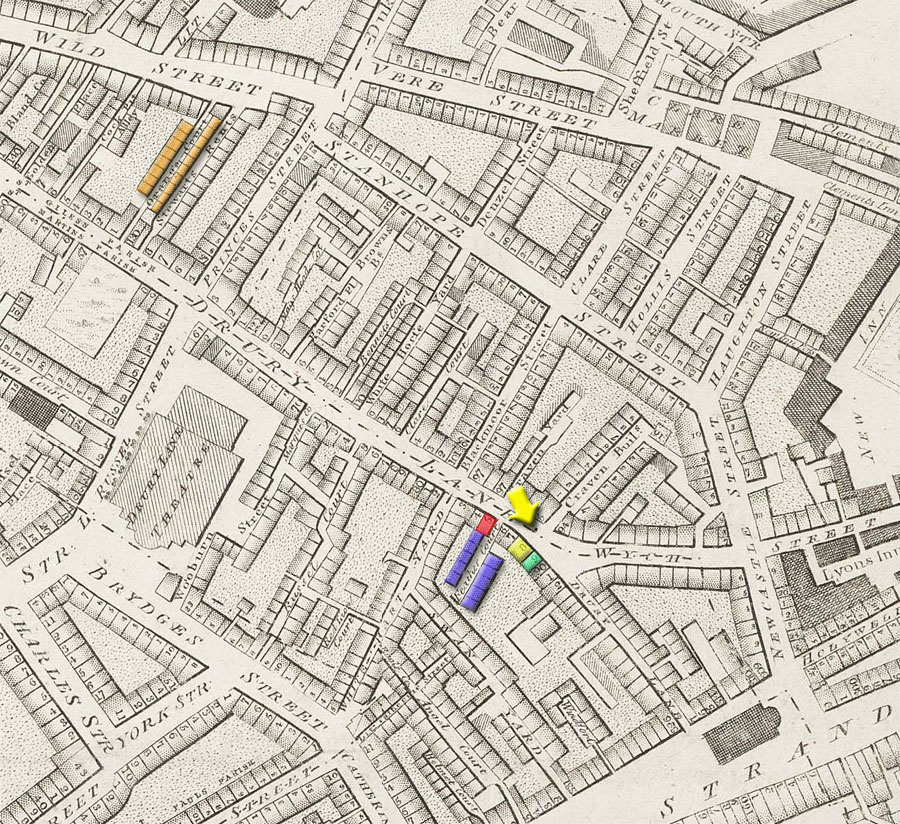

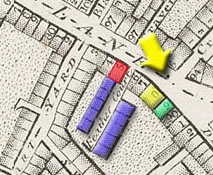

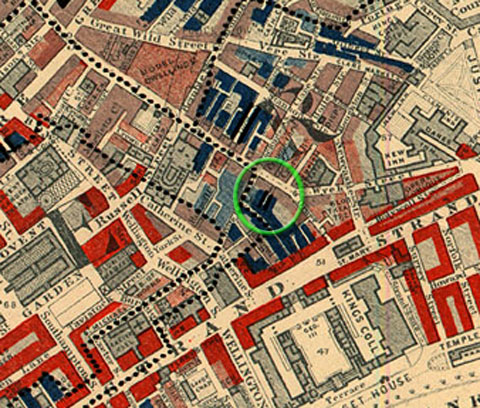

The house where Sarah was born is one of the ten houses shaded in blue in the map below:

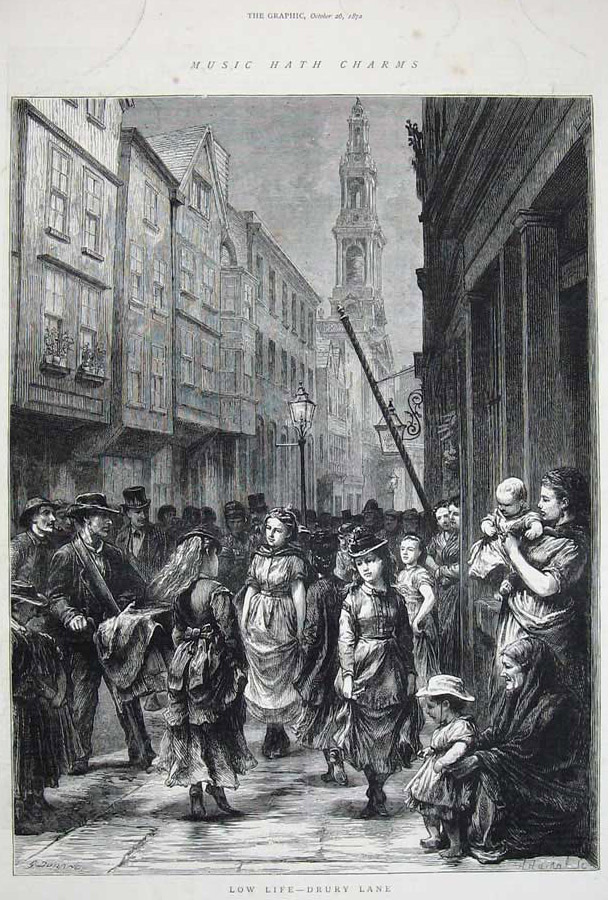

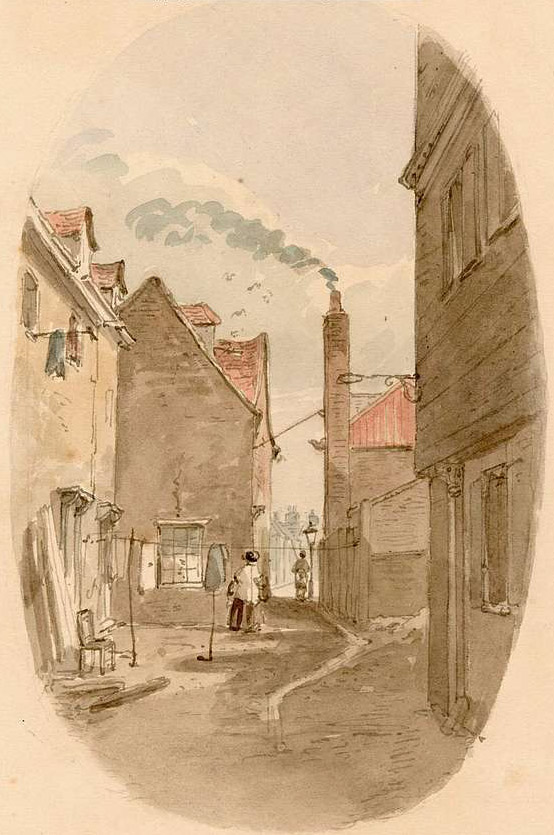

You may have seen this view before, drawn by an artist whom I can only credit by his initials, WHP; it's the Cock & Magpie pub at 88 Drury Lane, shaded yellow in the map, seen from the viewpoint of the yellow arrow; it's very close to Feathers Court:

It's a very popular subject for Victorian artists. The church in the background is St Mary-Le-Strand where Sarah was christened aged 1 on 01July 1846:

Aaaaw, it looks right Christmassy in that painting. But Sarah's home, in a courtyard behind the shops to the right of the picture, is probably freezing cold. Her dad James is absolutely skint - we know this from all the evidence - and there can't have been much money spare to pay for coal.

In the next picture, by the Victorian painter Henry George Hine, firemen are extinguishing a fire in Drury Lane. Check out the laundry dangling high to the left... someone's shirt, preserved in history for all time by the artist:

By the 1880s the Cock & Magpie is no longer a pub; the old buildings have lost their charm and look neglected:

iiiiiiii

iiiiiiii

In the picture below we see No. 89 Drury Lane, shaded green in the map. Next door, a bunch of chaps hang around outside the former site of the Cock & Magpie which now houses a jewellers shop and a bookshop. We are now tantalisingly close to Feathers Court; it's behind the tall forbidding building in the background:

The photo we see above was taken in 1880 for the publication Photographs of Old London, for the Society for Photographing Relics of Old London. The photographer is Henry Dixon, an absolute master of his art.

Henry Dixon took these photos, titled Old Houses in Drury Lane, because the Society recognised that ancient buildings like these were rapidly disappearing from London:

I like the very Victorian shop-sign above one of the two shops occupying the former Cock & Magpie building: Stockley, Bookseller, Noted for Cheap Books.

The building survived about another 20 years and was demolished c1900 as a part of the Aldwych redevelopment, but even then, in the days before Listed Buildings and planning regulations, it was recognised that the loss of this old building of character was a bit of a shame.

But let's go back to Drury Lane nearer to the time of the birth of our Sarah, because we have a fantastic piece of social history which some unnamed Victorian genius [though I think I can discern the style and the signature of Gustave Doré] just knew would be of interest to posterity. It was published in The Graphic newspaper of 26 October 1872.

We are again outside a pub on Drury Lane, just yards from the Partleton home, but it's not at all clear to our modern eyes exactly what is going on:

The title of the picture - Music Hath Charms - is a minor misquote from the poem The Mourning Bride, written by William Congreve in 1697:

This quote, and the subtitle of the engraving - Low Life - seem a bit harsh. The subjects of the picture are merely common people; I'm not sure they have particularly savage breasts to be soothed. But the message is still apparent. The girls dancing to the organ-grinder's tune are of the working-classes, perhaps of a different social class to the readers of the newspaper.

The lamp-post is the same one we saw in Henry Dixon's photograph:

I've recently come to recognise that the subjects of the engraving are simply working-class girls dancing to the music being ground out by the turning hand of the organ grinder. There is an interpretation which I read of The Graphic's message, that these were prostitutes dancing for trade; I'm now quite certain that this is incorrect.

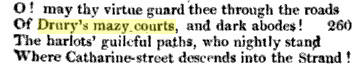

But prostitutes most certainly did proliferate on Drury Lane, and had done for centuries. The street was famous for it. Samuel Pepys has a rather comical entry in his famous diary, for 21 March 1665:

The poem below 'Of Walking the Streets by Night' by John Gay was written in 1721:

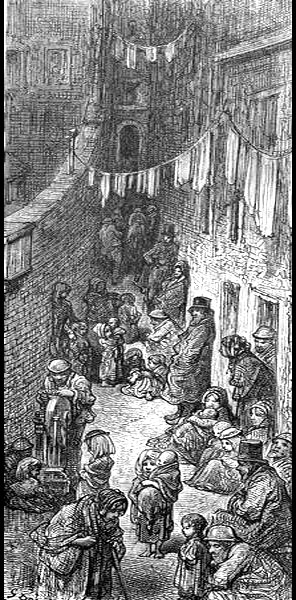

Feathers Court and the other 'dark abodes' off Drury Lane are rough. Very rough. The picture of the street below, definitely drawn by Doré, shows Orange Court, Drury Lane:

Orange Court is shaded orange in the map below:

The picture above comes from 'London: A Pilgrimage' by two Frenchmen, Blanchard Jerrold and Gustave Doré. Their book of 1872 was a big commercial success, but it created rather a stir in England because it concentrated only on the poverty of London, not on the glamorous bits.

Messieurs Jerrold and Doré were not making it up...

This article from 'Tait's Edinburgh Magazine' of 1848 explores exactly what was happening to housing around Drury Lane, exactly contemporaneous with our baby Sarah's time of living there:

So, a lot of slums and cheap housing south of Oxford Street had been demolished between 1845 and 1848. The effect of this was to force London's rapidly expanding population of the poor into ever-decreasing areas of remaining cheap housing concentrated around Drury Lane.

James Partleton, Sarah's dad, can only afford to rent one single room; a standard arrangement for poor people. There may have been a disgusting communal outside toilet - or equally likely you'll have to use a chamber pot, take it outside and swill it through the grating into the cesspit in the yard.

Cooking was done in a pot over the fire. James, his wife Mary Ann, and their six children including little baby Sarah, a total of eight people, are all squashed into one room, a very common situation which is illustrated as a typical arrangement by a Victorian artist below:

Feathers Court is an unsanitary place, a meeting place of killer diseases, recorded through decades of deaths. These are captured in the Partleton Tree page for Sarah's big brother Charles (1839-1916).

For some years the Partleton Tree has been just itching to get a glimpse inside Feathers Court; there are so many terrible stories abound about this place; prostitution; theft; murders; suicides; domestic violence.

But don't take my word for it - just read these reports from contemporary newspapers; the first one is 18 June 1846:

And this charming tale was reported in April 1866:

And this sad story is from 1838:

.png)

All this fuels our hunger to see what Feathers Court really looked like...

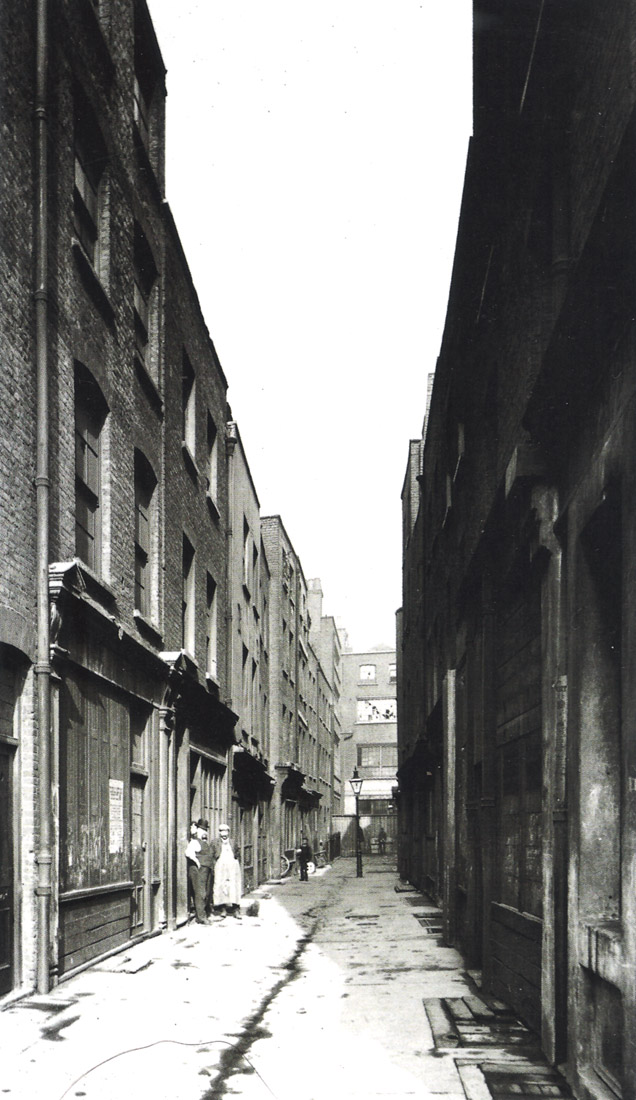

In May 2010, I was directed by Partleton Tree correspondent Linda King to a whole range of old photos held by English Heritage. And as it happens, one of these is of Feathers Court. Ok, this picture was taken more than 60 years after our Sarah had moved from Feathers Court. Indeed its demolition had commenced as a part of the Aldwych redevelopment, as we see the bricks accumulating in piles, but we get a stunning view of this cramped location of overcrowded living conditions... behold - Feathers Court:

One of those boarded-up shopfronts on the right may be the Blue Anchor, a pub which we know was located inside Feathers Court and which no doubt helped fuel the terrible drunkenness we read about in those old newspapers. We are standing in Feathers Court looking north towards its entrance to Drury Lane, through an archway directly ahead of us. We can't see the archway because it is hidden from view behind the temporary wooden gateway to the demolition site.

The view above is from the purple arrow in the map below:

And finally, after much circling around its environs, we are able to capture just a glimpse of Feathers Court from the outside, seen from the viewpoint of the red arrow in the map above. The engraving (of 1896) below comes courtesy of Richard Herbert, of Herbert Group who manufacture modern weighing technology.

Richard found our website while searching for his company's history on the internet. There's a clue in the picture... the firm of Hubbard and Walker, scalemakers, at the entrance archway to Feathers Court - 85 Drury Lane - were eventually taken over by the Herbert Company in the 1920s. Thanks Richard!

Hubbard & Walker at 85 Drury Lane is shaded red on our map. I believe the lady hovering in the shadows under the arch is - well, I hesitate to judge - but probably is a prostitute, from all the evidence we have.

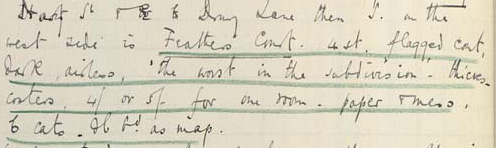

Charles Booth's surveyor visited Feathers Court when examining the area for Booth's famous poverty map in the late 1800s and in his own hand, recorded it to be 'the worst in the subdivision'...

We can see from the poverty map and legend below that Charles singled out Feathers Court in black lines, in contrast to the 'fairly comfortable' frontage on Drury Lane which we see in the engraving, as 'Lowest Class, Vicious, Semi-Criminal'

In September 1845, tuberculosis reigned at Feathers Court. Six-month-old Sarah must have been exposed to the TB bacterium, as her sister contracted the disease, and was probably infected. Victims of tuberculosis could live a very long time. It was a wasting disease (thus the 19th century term consumption), its sufferers usually not dying within days or weeks, but living with attacks and remissions that could last for years or decades.

TB allowed those infected to get married, have children, and pass the disease on to them. Families, therefore, could suffer from the infection for 2 or even 3 generations, passing it from parent/grandparent to children. In fact, for much of the century, physicians thought the disease was hereditary, not contagious. They believed that families had a predisposition to the illness. In fact, it is transmitted through the air and breathed in.

Only 10% of people who contracted tuberculosis actually developed the full disease. Sarah's sister Mary Ann is one of these. She got TB [Victorian medical term: Phthisis] and died at Feathers Court aged just 4 years old, tended by her mother as she coughed up blood:

Below we observe that in 20 days between 06 September and 26 September 1845, Mary Ann and four other little children had died in Feathers Court and were buried in the nearby Russell Court burial ground.

We can also see that in Sarah's building alone - No. 7 Feathers Court - three children died within 5 days of each other, including a brother and sister. These other children may or may not have died of TB. You could take your pick of at least half a dozen killer diseases; Typhoid, Scarlet Fever, Smallpox, Measles. Today we are protected from TB by the BCG vaccination which we get at school, though tuberculosis is again on the increase due to resistant strains.

Sarah's about to leave Feathers Court, a move which will kill her, but we shall pause for a couple of further looks at her neighbourhood in several more breathtaking photos from English Heritage. The first of these shows us Blackmoor Street. This photo was taken on 09 October 1902 - 53 years after Sarah's death, but I reckon it would still be 100% recognisable:

The alleyway turning to the left, directly ahead of us, is the eastern entrance of Clare Court, which shows that we are looking northwards along Blackmoor Street from the viewpoint of the green arrow in the map below:

These concentrations of overcrowded working-class accommodation were known to the Victorians as rookeries which I think is a bit of a slur against rooks, who to my knowledge live in wholesome nests not festering polluted slums.

But the next photo, from the blue arrow, reveals that Drury Lane is not all completely dilapidated.

These are Craven Buildings, seen from the viewpoint of the blue arrow.

The advertising lamp at the left edge of the picture says Mr A Morgan, provider of Funerals to All Classes. Sarah's mum and dad probably didn't use Mr Morgan for their daughter Mary Ann's funeral in 1845 as it says he wasn't established till 1850.

Let's get back to the rookeries - we should face it, they are more interesting...

What we see above is Clare Court, highly typical of the unsanitary back-streets of the area, broken windows evident in the building directly ahead. This photograph, from the viewpoint of the orange arrow in the map below, was taken on 11 June 1906, nearly 60 years after Sarah had left the area, but again, I'm sure you'll agree, logically it hasn't changed much in those 6 decades.

These photographs were clearly taken with a view to posterity as the buildings were soon to be torn down, which may partially explain the broken windows, and we should thank the photographer, who is anonymous. The entire area was gradually demolished during the first decade of the 20th century and redeveloped as the Aldwych.

Anyhoo, it's high time we got back to our Sarah. We learned earlier that in the 1840s, slum clearances south of Oxford Street had the effect of pressuring the poor into ever-decreasing rookeries, and this had the effect of forcing the rent up for the remaining cheap housing at Drury Lane, and this may have been the reason that James Partleton took his family to the cheaper area of Lambeth on the south bank of the River Thames in 1847.

In the map below, we see the geographical relationship between Drury Lane, circled blue, and Lambeth, circled yellow, south of the river:

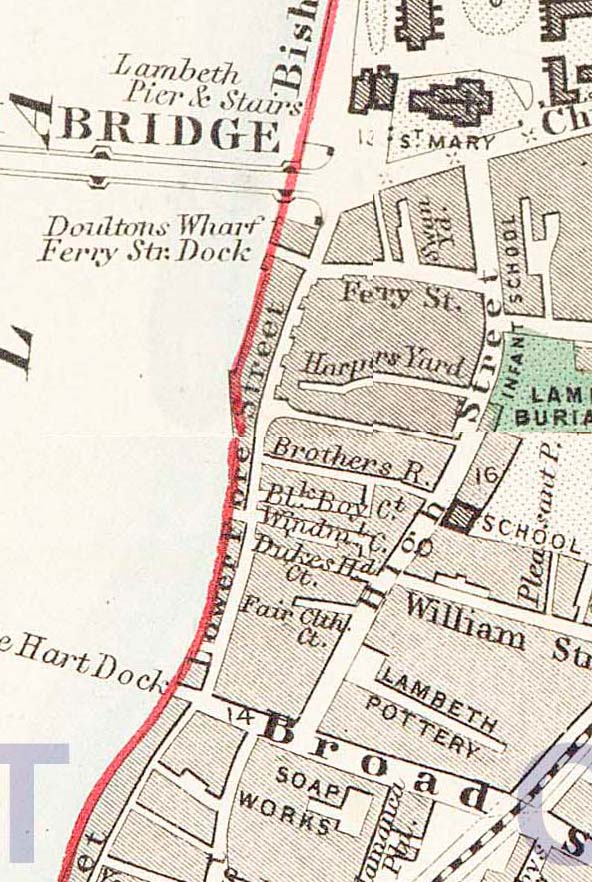

Most other members of the Partleton family had already moved to Lambeth many years before. Four-year-old Sarah found herself living at Duke's Head Court, Lower Fore-Street, Lambeth which we see in the watercolour painting below:

The decision to move to move to Duke's Head Court was to prove fatal for little Sarah Partleton:

As evidenced by the death certificate, little Sarah died of the dread disease cholera aged just 4 years and 4 months.

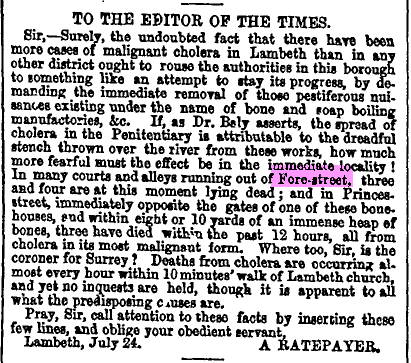

Duke's Head Court, Sarah's house, is one the alleys 'running out of Fore Street' which is mentioned in this letter to The Times on 25 July 1849, two weeks after Sarah's death:

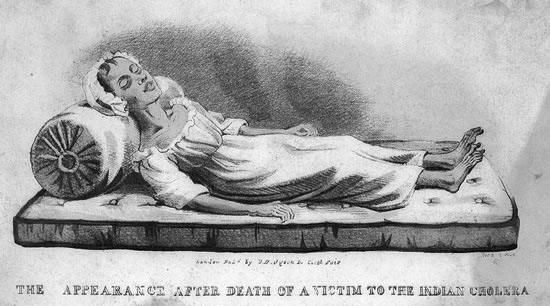

Cholera is one of the most rapidly fatal illnesses known. Death is brought about by massive fluid loss by liquid diarrhorea and vomiting. In a common scenario for an adult, the disease progresses from the first symptoms to low blood pressure and kidney failure caused by loss of fluid in 4 to 12 hours, with death following in 18 hours. In the case of little Sarah, who is far from an adult, death occurred just 11 hours after the first symptoms, as recorded on her death certificate.

The dehydration caused by cholera is apparent in the illustration below. What those 11 hours of sickness must have been like for the poor little scrap, and indeed for her poor mother who had to sign her death certificate with a cross, defies imagination:

The death of little Sarah was but one statistic of the London cholera epidemic of 1849 which killed 14,137 people.

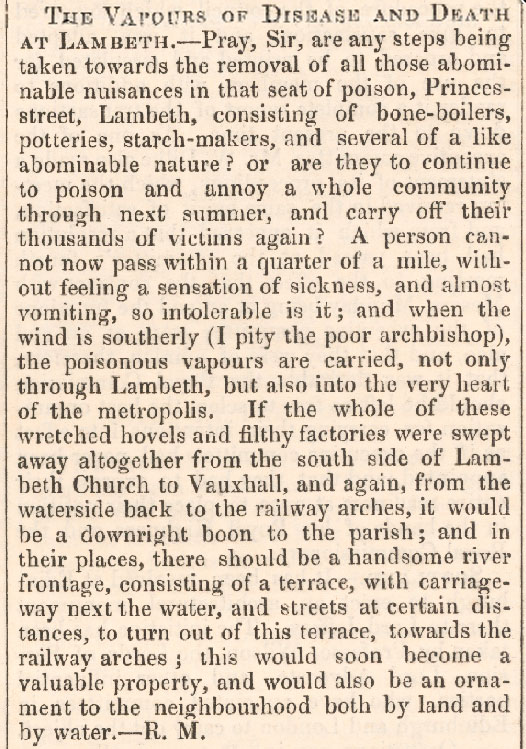

The Victorians did not know how the disease was transmitted, as is demonstrated in this letter to The Builder magazine of 16 February 1850. Common belief was that cholera was carried by bad air:

So, let's wind the clock back eight months to September 1848 and have a look at Dr John Snow, a hero of mine, who was to lay bare the cause of the spread of cholera:

Left: John Snow

Left: John Snow

John Snow, born in York in 1813, had witnessed at close quarters the first epidemic of cholera in Britain in 1831/1832 in Newcastle, when he was an apprentice physician. He moved to London in the late 1830s.

When the very first cases of the dreaded cholera started to reappear in London in 1848, John made it his business to analyse the data and seek the truth. Lower Fore Street - the exact location of Duke's Head Court where the Partleton family are living - is mentioned twice:

Cholera is in fact transmitted through drinking water which has been contaminated by faeces. Unfortunately, cholera-contaminated water can commonly appear clear and pure. About one million V. cholerae bacteria must typically be ingested to cause cholera in an adult. John Snow's assertion that water was the cause seems obvious in hindsight, given that the symptoms are gastric, and he was not the only person supporting this theory, and it was not a new theory. But the common belief at the time was that cholera was transmitted by bad air, and John's careful analysis received a lukewarm reception among the Victorian medical establishment.

So, by sheer bad luck, Sarah Partleton is living at Duke's Head Court, just a few doors away from two of the first five victims of cholera, who both reside on Lower Fore Street. We see both streets in the map below. But where are the Partleton family getting their drinking water?

John Snow, as circled in blue in his report, suggests that they were drinking it straight from a bucket from the Thames, which sounds shocking; some might say downright stupid. However as we shall see, if you took your water from the tap, this also came straight from the Thames.

The thronging millions in London at this time could get water in a number of ways: Drinking water had traditionally been piped in from miles away in primitive lead pipes (called conduits) from fresh streams outside of London. These were not available in Lambeth; and in any case they were primarily for the rich, though it was not uncommon for conduits to be illicitly tapped into by the less well-off.

In the 19th century, for some, this became supplemented by water distributed directly to the home by new water companies, in most cases drawn more or less straight from the Thames. Poor folk, of course, didn't always have taps in their houses, but they often had access to the exactly same supplies from communal standpipes in the street.

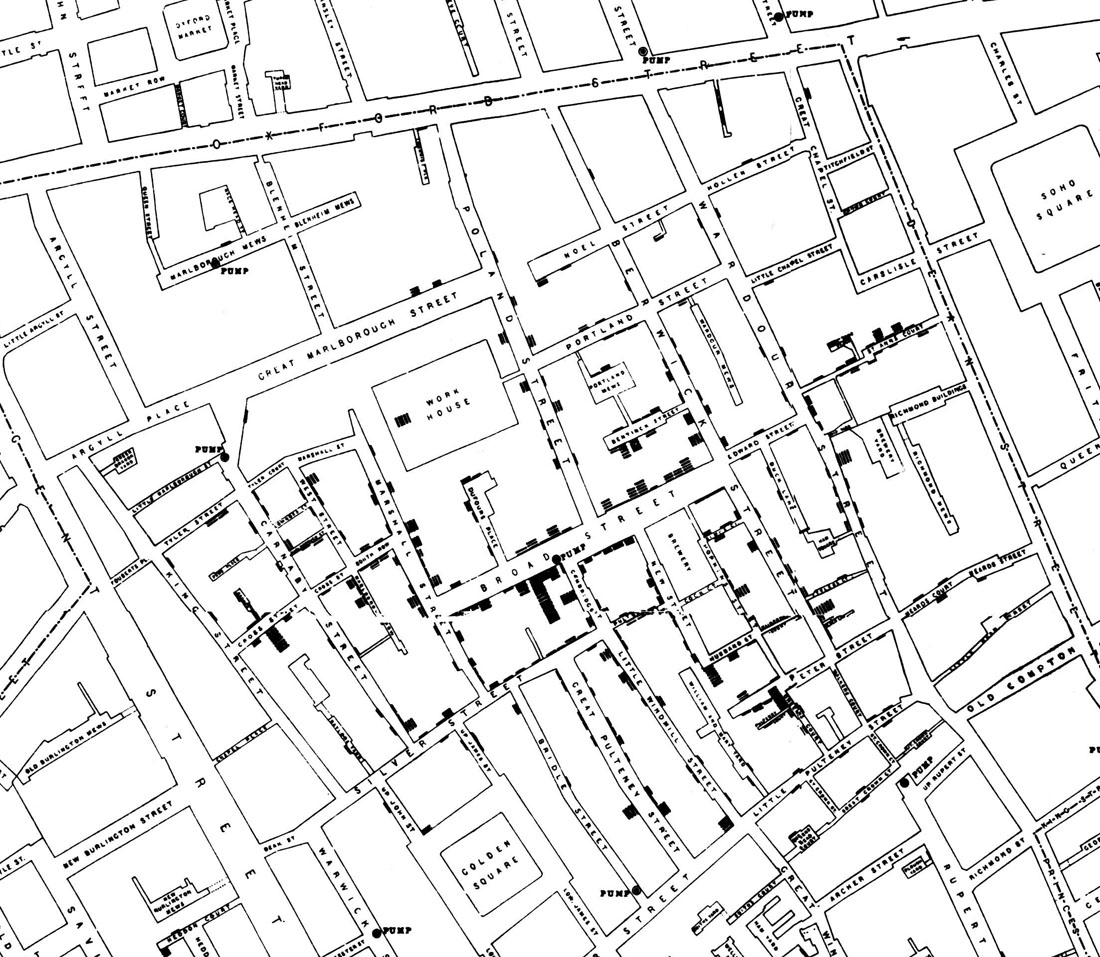

There were also numerous public wells with pump-handles dotted around the streets of London. These were OK unless they became contaminated by nearby cesspits.

In the 1854 cholera outbreak, John Snow was quick to react. Unknown to the residents, the source was a street pump on the corner of Broad Street and Cambridge Street, just south of Oxford Street, seen in the map above. The area had already recently been provided with new sewers, but the well which fed this pump was only 3 feet from a remaining old cesspit, serving No. 40 Broad Street. In a now-legendary intervention, John Snow plotted the location of local deaths (black bars on the above map), talked to residents, and concluded that the pump was the centre and the source of the cholera. John then attended the local church council meeting and persuaded the council to remove the pump handle. They grudgingly acceded.

The outbreak subsided very soon afterwards, and the intervention was hailed as a success, though John Snow carefully and professionally noted that the end of the outbreak might well have occurred anyway due to the massive flight of residents from the area which always followed outbreaks of cholera.

Presumably Sarah Partleton's dad didn't have the means to run away from Lambeth in 1849.

The modern site at Broad Street is marked by a memorial replica pump, and the nearby pub was later named The John Snow which is a bit ironic since he was teetotal.

Anyhoo, lets get back to 1849 and the death of Sarah. I've gone on a bit about cholera but I'll just bring the page to a close and tie up the loose ends on the water supply.

Many people had no running water at all, but in Lambeth in the early 1800s it had become quite common to have it piped into communal tanks in domestic buildings. This was not a continuous supply; the pipes would refill the tank periodically. Supplying Lambeth were two private water companies: the Lambeth Water Company and the Southwark & Vauxhall Water Company.

So, in the 1800s, the versatile Thames served two purposes, cheek-by-jowl... water-supply and sewer, all in one handy resource:

The above illustration by the famous cartoonist George

Cruikshank is actually a response to the 1831 epidemic. It shows the owner of

the Southwark company, John Edwards Vaughn, as Neptune crowned with a chamber

pot,

enthroned on a toilet which empties directly on the source of the

Southwark water works, which is also fed by sewer outfalls. From the comments of the folk on

the riverbank "![]() ",

we see that even in 1831, the links between drinking water, sewage, and the

disease was suspected.

",

we see that even in 1831, the links between drinking water, sewage, and the

disease was suspected.

Outlined in green in John Cary's 1785 map below, we see the stretch of Thames which is depicted in Mr Cruikshank's drawing:

Let's have another look at the cartoon. Its tongue-in-cheek latin title translates to 'Public Health is the Highest Law'.

The lines of a poem by Alexander Pope are appended as an ironic subtitle...

Hail long-expected days

That Thames's glory to the stars shall raise

In Richard Horwood's lovely map of London, 1799 edition, below, we can see that George Cruikshank stood on Queen Street Bridge (later Southwark Bridge) - probably holding a handkerchief to his nose - and looked eastward to London Bridge from the point of the purple arrow in the map. I have taken the liberty of adding the bridge - which wasn't built till 1819. We can match the places in Cruikshank's cartoon; Horseshoe Alley at the yellow arrow in the drawing, circled in yellow in the map; the Southwark Water Works, blue arrow and blue circle, and Southwark Cathedral aka St Saviour's picked out in red.

The strange metal object upon which Vaughn sits is the waterworks water-inlet, which was anchored to the riverbed, though it's unclear to me if the head floated permanently on the surface or, as seems more likely, was only revealed at low tide. Either way, it sucked a diabolic chemical and bacterial soup of pollution directly from the Thames. I reckon its strainers would have needed unblocking pretty frequently. Assuming Cruikshank's drawing to be correct - and we have no reason to think otherwise - in 1831, it was located at the green circle in the map:

Looking at these maps I have found myself repeatedly making the mistake of assuming that the River Thames always flows from left to right on its passage to the sea. Actually this is not true at all. The water flows back and forth, reversing direction depending on the tide... and when the tide's on the turn, it doesn't move at all, like a stagnant pond. This makes the situation a whole lot worse as new sewage continuously pouring into the river is carried away painfully slowly: creeping generally eastwards, two steps forward, one step back, the same stinking bilge slops limply in and out, languidly dawdling towards the Thames estuary - a process which can take days.

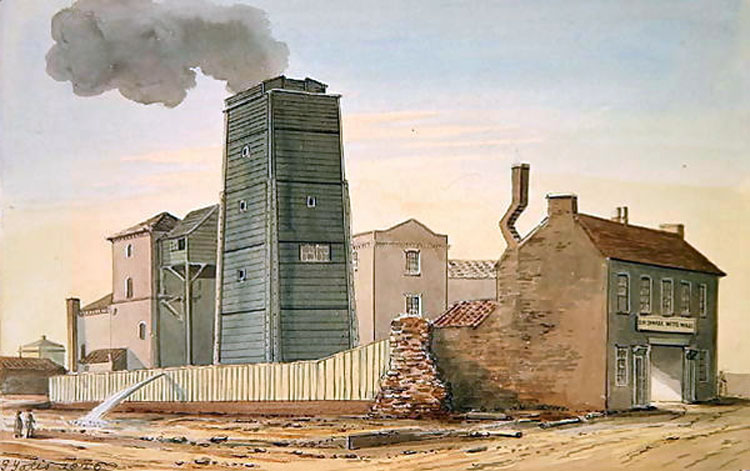

Watercolourist Gideon Yates took the trouble to give us a view of the Southwark company's water works in 1826, from the viewpoint of the orange arrow in the map above:

Thanks to Richard Horwood's meticulous mapping which I never tire of praising, and thanks to Yates' warts-and-all depiction, we notice that the buildings nearest the orange arrow in the map have been demolished at some point between 1799 and 1826, but we can still see the remnants of that demolition - a mess which hasn't been very carefully or lovingly tidied up. It doesn't make a very reassuring scene, does it?

A gout of surplus water gushes from the side of the works, presumably wending its way, eventually, back, via the gullies and drains, to the smelly river whence it came.

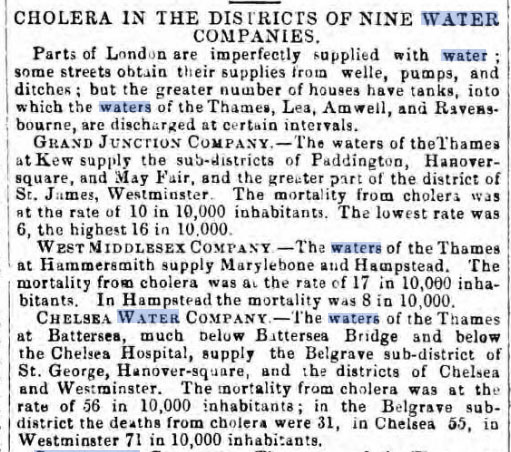

In Lambeth and Southwark, amid the cholera outbreak of 1849, it really didn't matter which company you got your water from. They had moved their sources a mile or so west, near to Waterloo Bridge - less than a mile from Southwark Bridge, which would make no difference to the water quality. All the water supplied to districts south of the Thames was seriously contaminated. The unproven link between water and cholera was clearly suspected, as reported in the Morning Post on 09 January 1850:

The point the newspaper was making, quite effectively, was that the further downstream in the Thames you obtained your source of water, the more likely your were to die from drinking it.

In 1850, the microbiologist Arthur Hassall, who obviously had a nice sense of humour, wrote in A Microscopic Examination of the Water Supplies to the Inhabitants of London:

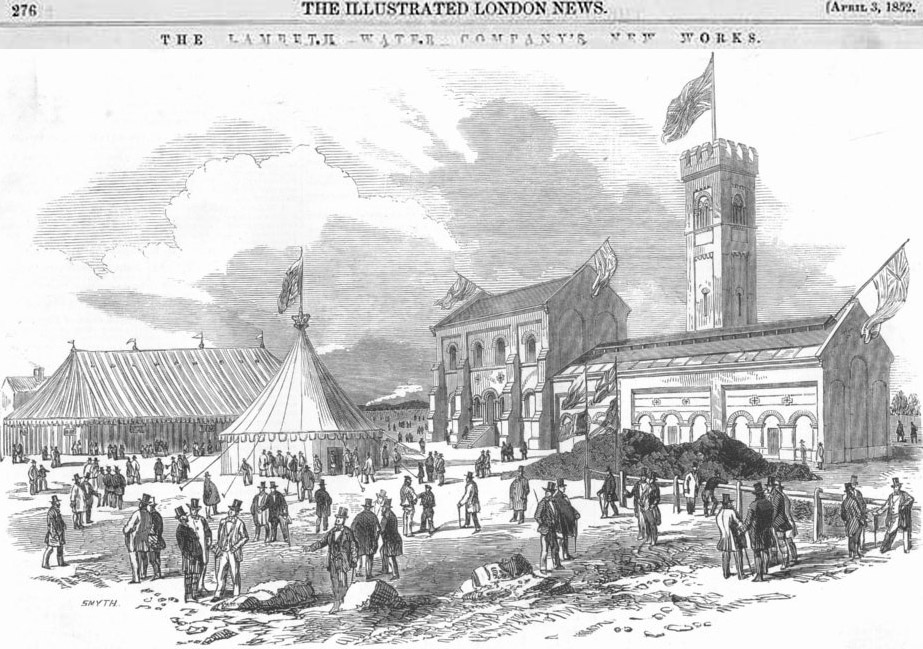

In 1852, the Lambeth Water Company moved its source 22 miles to Thames Ditton, a long way upstream of London's sewers; we see its opening ceremony in the Illustrated London News of 03 April 1852:

In the same year, the Water Metropolis Act was passed and the Southwark & Vauxhall company were also required to relocate their source at the earliest opportunity - though its seems by 1854, they still hadn't managed it.

In the 1854 outbreak of cholera, John Snow seized the opportunity to analyse the data of cholera deaths. It was a very difficult and painstaking task identifying which company supplied which person, but he found that in a four-week period between 08 July and 05 August, in exactly the same area in Lambeth, 286 of the 334 victims had used Southwark & Vauxhall water whereas just 14 of the victims had used the Lambeth company water which came from the new Thames Ditton works.

Incredibly, even with this effectively conclusive statistical evidence, Snow's work was not wholly accepted by the medical establishment, because cholera could not be seen by the microscopes of the time, and it was not till the 1870s, Louis Pasteur, and improved microscopy that the true cause of cholera was proved for certain.

Left: Cholera Bacteria

Left: Cholera Bacteria

If only the Victorians had known... despite being one of the most rapidly fatal diseases known to man, which is still killing people in the third world today, cholera is ridiculously easy to cure. The right mixture of sugar and salt dissolved in clean water in the right proportions allows the body to be rehydrated, whereupon the human immune system destroys the cholera bacteria without much drama. This is successful in over 99% of cases. Small consolation for our Sarah.

To experience a full and frank Victorian description of low life in Drury Lane, click here.

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... or would you like to discuss any of the history... or if you have any observations or comments... all information is always welcome so why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'In Their Shoes' Page.