Drury Lane

Have you seen the muffin man?

The muffin man, the muffin man.

Have you seen the muffin man,

He lives down Drury Lane...

He lives down Drury Lane...

The following is from Chapter 6 of the book "Days and Nights in London", an account of the experiences of its author J. Ewing Ritchie:

The book describes life as it would have been experienced at first hand by the family of James Partleton (1806-1873) who lived in a "Low Lodging-House" in Feathers Court, Drury Lane. The Partleton Tree expressly dissociates itself from the Victorian racism, intolerance and political incorrectness contained in this book of 1880! These were the opinions of the priggish Mr Ritchie and do NOT reflect the opinions of the website!

Days and Nights in London, by J. Ewing Ritchie, 1880

THE LOW LODGING-HOUSE

Is chiefly to be found in Whitechapel, in Westminster, and in Drury Lane. It is in such places the majority of our working men live, especially when they are out of work or given to drink; and the drinking that goes on in these places is often truly frightful, especially where the sexes are mixed, and married people, or men and women supposed to be such, abound. In some of these lodging- houses as many as two or three hundred people live ; and if anything can keep a man down in the world, and render him hopeless as to the future, it is the society and the general tone of such places. Yet in them are to be met women who were expected to shine in society- students from the universities - ministers of the Gospel - all herding in these filthy dens like so many swine. It is rarely a man rises from the low surroundings of a low lodging-house. He must be a very strong man if he does. Such a place as a Workman's City has no charms for the class of whom I write. Some of them would not care to live there. It is no attraction to them that there is no public-house on the estate, that the houses are clean, that the people are orderly, that the air is pure and bracing. They have no taste or capacity for the enjoyment of that kind of life. They have lived in slums, they have been accustomed to filth, they have no objection to overcrowding, they must have a public-house next door. This is why they live in St. Giles's or in Whitechapel, where the sight of their numbers is appalling, or why they crowd into such low neighbourhoods as abound in Drury Lane. Drury Lane is not at all times handy for their work. On the contrary, some of its inhabitants come a long way. One Saturday night I met a man there who told me he worked at Aldershot. Of course to many it is convenient. It is near Covent Garden, where many go to work as early as 4 A.M. ; and it is close to the Strand, where its juvenile population earn their daily food. Ten to one the boy who offers you "the Hevening Hecho," the lass who would fain sell you cigar-lights and flowers, the woman who thrusts the opera programme into your carriage as you drive down Bow Street, the questionable gentleman who, if chance occurs, eases you of your pocket-handkerchief or your purse, the poor girl who, in tawdry finery, walks her weary way backwards and forwards in the Strand, whether the weather be wet or dry, long after her virtuous sisters are asleep- all hail from Drury Lane. It has ever been a spot to be shunned.

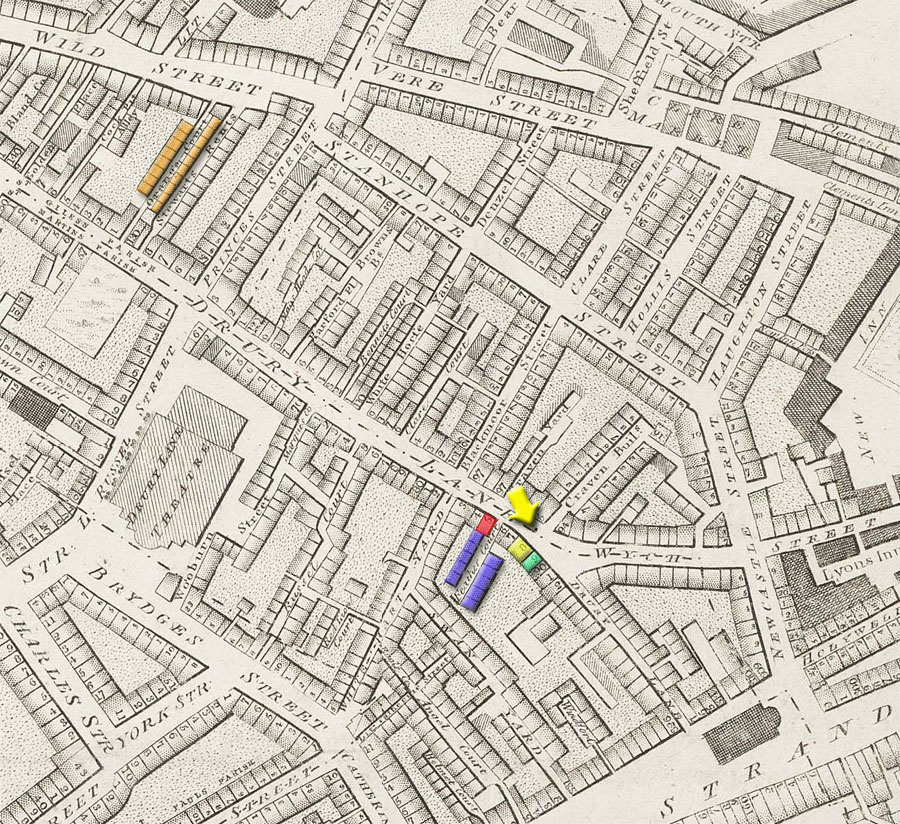

It is not of Drury Lane itself, but of its mazy courts that I write. Drury

Lane is a shabby but industrious street. It is inhabited chiefly by tradespeople,

who, like all of us, have to work hard for their living; but at the back of

Drury Lane - on the left as you come from New Oxford Street - there run courts

and streets as densely inhabited as any of the most crowded and filthy parts of

the metropolis, and compared with which Drury Lane is respectability itself. A

few days since I wanted to hear Happy William in a fine new chapel they have got

in Little Wild Street. As I went my way, past rag-shops and cow-houses, I found

myself in an exclusively Irish population, some of whom were kneeling and

crossing themselves at the old Roman Catholic chapel close by, but the larger

number of whom were drinking at one or other of the public-houses of the

district. At the newspaper-shop at the corner, the only bills I saw were those

of The Flag of Ireland, or The Irishman, or The Universe. In about half an hour

there were three fights, one of them between women, which was watched with

breathless interest by a swarming crowd, and which ended in one of the

combatants, a yellow-haired female, being led to the neighbouring hospital. On

his native heather an Irishman cares little about cleanliness. As I have seen

his rude hut, in which the pigs and potatoes and the children are mixed up in

inextricable confusion, I have felt how pressing is the question in Ireland, not

of Home Rule, but of Home Reform. I admit his children are fat and numerous, but

it is because they live on the hill-side, where no pestilent breath from the

city ever comes.

In the neighbourhood of Drury Lane it is different; there is no fresh air

there, and the only flowers one sees are those bought at Covent Garden.

Everywhere on a summer night (she "has no smile of light" in Drury Lane), you

are surrounded by men, women, and children, so that you can scarce pick your

way. In Parker Street and Charles Street, and such-like places, the houses seem

as if they never had been cleaned since they were built, yet each house is full

of people - the number of families is according to the number of rooms. I should

say four-and- sixpence a week is the average rent for these tumble-down and

truly repulsive apartments. Children play in the middle of the street, amidst

the dirt and refuse; coster-mongers, who are the capitalists of the district,

live here with their donkeys; across the courts is hung the family linen to dry.

You sicken at every step. Men stand leaning gloomily against the sides of the

houses; women, with unlovely faces, glare at you sullenly as you pass by.

The City Missionary is, perhaps, the only one who comes here with a friendly

word, and a drop of comfort and hope for all. Of course the inhabitants are as

little indoors as possible. It may be that the streets are dull and dirty, but

the interiors are worse. Only think of a family, with grown- up sons and

daughters, all living and sleeping in one room! The conditions of the place are

as had morally as they are physically.

It is but natural that the people drink more than they eat, that the women

soon grow old and haggard, and that the little babes, stupefied with gin and

beer, die off, happily, almost as fast as they are born. Here you see men and

women so foul and scarred and degraded that it is mockery to say that they were

made in the image of the Maker, and that the inspiration of the Almighty gave

them understanding; and you ask is this a civilised land, and are we a Christian

people?

No wonder that from such haunts the girl gladly rushes to put on the

harlot's livery of shame, and comes here after her short career of gaiety to die

of disease and gin. In some of the streets are forty or fifty lodging-houses for

women or men, as the case may be. In some of these lodging-houses there are men

who make their thirty shillings or two pounds a week. In others are the

broken-down mendicants who live on soup-kitchens and begging. You can see no

greater wretchedness in the human form than what you see here. And, as some of

these lodging-houses will hold ninety people, you may get some idea of their

number. When I say that the sitting-room is common to all, that it has always a

roaring fire, and that all day, and almost all night long, each lodger is

cooking his victuals, you can get a fair idea of the intolerable atmosphere, in

spite of the door being ever open. It seemed to me that a large number of the

people could live in better apartments if they were so disposed, and if their

only enjoyment was not a public-house debauch. The keepers of these houses

seemed very fair-spoken men.

I met with only one rebuff, and that was at a model house in Charles Street.

As I airily tapped at the window, and asked the old woman if I could have a bed,

at first she was civil enough, but when I ventured to question her a bit she

angrily took herself off, remarking that she did not know who I was, and that

she was not going to let a stranger get information out of her.

As to myself, I can only say that I had rather lodge in any gaol than in the

slums of Drury Lane. The sight of sights in this district is that of the

public-houses and the crowds who fill them. On Saturday every bar was crammed;

at some you could not get in at the door. The women were as numerous as the men;

in the daytime they are far more so; and as almost every woman has a child in

her arms, and another or two tugging at her gown, and as they are all formed

into gossiping knots, one can imagine the noise of such places.

D.D. - City readers will know whom I refer to- has opened a branch

establishment in Drury Lane, and his place was the only one that was not

crowded. I can easily understand the reason - one of the regulations of D.D. 's

establishment is that no intoxicated person should be served. I have reason to

conclude, from a conversation I had some time ago with one of D.D.'s barmen,

that the rule is not very strictly enforced; but if it were carried out at all

by the other publicans in Drury Lane I am sure there would be a great falling

off of business. Almost every woman had a basket; in that basket was a bottle,

which, in the course of the evening, was filled with gin for private

consumption; and it was quite appalling to see the number of little pale-faced

ragged girls who came with similar bottles on a similar errand. When the liquor

takes effect, the women are the most troublesome, and use the worst language.

On my remarking to a policeman that the neighbourhood was, comparatively

speaking, quiet, he said there had been three or four rows already, and pointed

to a pool of blood as confirmation of his statement. The men seemed all more or

less stupidly drunk, and stood up one against another like a certain Scotch

regiment, of which the officer, when complimented on their sobriety, remarked

that they resembled a pack of cards - if one falls, down go all the rest.

Late hours are the fashion in the neighbourhood of Drury Lane. It is never

before two on a Sunday morning that there is quiet there. Death, says Horace,

strikes with equal foot the home of the poor and the palace of the prince. This

is not true as regards low lodging-houses. Even in Bethnal Green the Sanitary

Commission found that the mean age at death among the families of the gentry,

professionalists, and richer classes of that part of London was forty-four,

whilst that of the families of the artisan class was about twenty- two.

Everyone - for surely everyone has read Mr. Plimsoll's appeal on behalf of

the poor sailors - must remember the description of his experiences in a

lodging-house of the better sort, established by the efforts of Lord Shaftesbury

in Fetter Lane and Hatton Garden. "It is astonishing," says Mr. Plimsoll, "how

little you can live on when you divest yourselves of all fancied needs. I had

plenty of good wheat bread to eat all the week, and the half of a herring for a

relish (less will do, if you can't afford half, for it is a splendid fish), and

good coffee to drink, and I know how much - or, rather how little - roast

shoulder of mutton you can get for twopence for your Sunday's dinner."

I propose to write of other lodging- houses- houses of a lower character,

and filled, I imagine, with men of a lower class. Mr. Plimsoll speaks in tones

of admiration of the honest hard-working men whom he met in his lodging- house.

They were certainly gifted with manly virtues, and deserved all his praise. In

answer to the question, What did I see there? He replies: "I found the workmen

considerate for each other. I found that they would go out (those who were out

of employment) day after day, and patiently trudge miles and miles seeking

employment; returning night after night unsuccessful and dispirited, only,

however, to sally out the following morning with renewed determination. They

would walk incredibly long distances to places where they heard of a job of

work; and this, not for a few days, but for many, many days. And I have seen

such a man sit down wearily by the fire (we had a common room for sitting, and

cooking, and everything), with a hungry, despondent look - he had not tasted

food all day - and accosted by another, scarcely less poor than himself, with

'Here, mate, get this into thee,' handing him at the same time a piece of bread

and some cold meat, and afterwards some coffee, and adding, 'Better luck

to-morrow; keep up your pecker.' And all this without any idea that they

were practising the most splendid patience, fortitude, courage, and generosity I

had ever seen.

Perhaps the eulogy is a little overstrained. Men, even if they are not

working men, do learn to help each other, unless they are very bad indeed; and

it does not seem so surprising to me as it does to Mr. Plimsoll that even such

men "talk of absent wife and children." Certainly it is the least a husband and

the father of a family can do.

The British working man has his fair share of faults, but just now he has

been so belaboured on all sides with praise that he. is getting to be rather a

nuisance. In our day it is to be feared he is rapidly degenerating. He does not

work so well as he did, nor so long, and he gets higher wages. One natural

result of this state of things is that the class just above him - the class who,

perhaps, are the worst off in the land - have to pay an increased price for

everything that they cat and drink or wear, or need in any way for the use of

their persons or the comfort and protection of their homes. Another result, and

this is much worse, is that the workman spends his extra time and wages in the

public-houses, and that we have an increase of paupers to keep and crime to

punish. There is no gainsaying admitted facts; there is no use in boasting of

the increased intelligence of the working man, when the facts are the other way.

As he gets more money and power, he becomes less amenable to rule and reason.

Last year, according to Colonel Henderson's report, drunk and disorderly cases

had increased from 23,007 to 33,867. It is to be expected the returns of the

City police will be equally unsatisfactory. As I write, I take the following

from The Echo: In a certain district in London, facing each other, are two

corner- houses in which the business of a publican and a chemist are

respectively carried on. In the course of twenty-five years the houses have

changed hands three times, and at the last change the purchase money of the

public-house amounted to £14,300, and that of the chemist's business to only

£1,000. Of course the publican drives his carriage and pair, while the druggist

has to use Shanks's pony.

But this is a digression. It is of lodging-houses I write. It seems that

there are lodging-houses of many kinds. Perhaps some of the best were those of

which Mr. Plimsoll had experience. The Peabody buildings are, I believe, not

inhabited by poor people at all. The worst, perhaps, are those in

Flower and Dean Street, Spitalfields, and the

adjacent district. One naturally assumes that no good can come out of Flower and

Dean Street, just as it was assumed of old that no good could come out of

Nazareth. This was illustrated in a curious way the other day. One of the

earnest philanthropists connected with Miss Macpherson's Home of Industry at the

corner, was talking with an old woman on the way of salvation. She pleaded that

on that head she had nothing to learn. She had led a good life, she had never

done anybody any harm, she never used bad language, and, in short, she had lived

in the village of Morality, to quote John Bunyan, of which Mr. Worldly Wiseman

had so much to say when he met poor Christian, just as he had escaped with his

heavy burden on his shoulder out of the Slough of Despond, and that would not do

for our young evangelist.

"My good woman," said he sadly, "that is not enough. You may have been all

you say, and yet not be a true Christian after .all."

"Of course it ain't," said a man who had been listening to the

conversation. "You'll never get to heaven that way. You must believe on the Lord

Jesus Christ, and then you will be saved."

"Ah," said the evangelist, "you know that, do you? I hope you live

accordingly."

"Oh yes; I know it well enough," was the reply; "but of course I can't

practise it. I am one of the light-fingered gentry, I am, and I live in Flower

and Dean Street ;" and away he hurried as if he saw a policeman, and as if he

knew that he was wanted.

The above anecdote, the truth of which I can vouch for, indicates the sort

of place Flower and Dean Street is, and the kind of company one meets there. It

is a place that always gives the police a great deal of trouble. Close by is a

court, even lower in the world than Flower and Dean Street, and it is to me a

wonder how such a place can be suffered to exist. What with Keane's Court and

Flower and Dean Street the police have their hands pretty full day and night,

especially the hatter. Robbery and drunkenness and fighting and midnight brawls

are the regular and normal state of affairs, and are expected as a matter of

course. When I was there last a woman had been taken out of Keane's Court on a

charge of stabbing a man she had inveigled into one of the houses, or rather

hovels- you can scarcely call them houses in the court. She was let off as the

man refused to appear against her, and the chances arc that she will again be at

her little tricks. They have rough ways, the men and women of this district;

they are not given to stand much upon ceremony; they have little faith in moral

suasion, but have unbounded confidence in physical force. A few miles of such a

place, and London were a Sodom and Gomorrah.

But I have not yet described the street. We will walk down it, if you

please. It is not a long street, nor is it a very new one; but is it a very

striking one, nevertheless. Every house almost you come to is a lodging- house,

and some of them are very large ones, holding as many as four hundred beds. Men

unshaven and unwashed are standing loafing about, though in reality this is the

hour when, all over London, honest men are too glad to be at work earning their

daily bread. A few lads and men are engaged in the intellectual and fashionable

amusement known as pitch and toss. Well, if they play fairly, I do not know that

City people can find much fault with them for doing so. They cannot get rid of

their money more quickly than they would were they to gamble on the Stock

Exchange, or to invest in limited liability companies or mines which promise

cent. per cent. and never yield a rap but to the promoters who get up the

bubble, or to the agent who, as a friend, begs and persuades you to go into

them, as he has a lot of shares which he means to keep for himself, but of

which, as you are a friend, and as a mark of special favour, he would kindly

accommodate you with a few.

But your presence is not welcomed in the street. You are not a lodger, that

is clear. Curious and angry eyes follow you all the way. Of course your presence

there- the apparition of anything respectable- is an event which creates alarm

rather than surprise.

In the square mile of which this street is the centre, it is computed are

crowded one hundred and twenty thousand of our poorest population- men and women

who have sunk exhausted in the battle of life, and who come here to hide their

wretchedness and shame, and in too many cases to train their little ones to

follow in their steps. The children have neither shoes nor stockings. They are

covered with filth, they are innocent of all the social virtues, and here is

their happy hunting- ground; they are a people by themselves.

All round are planted Jews and Germans. In Commercial Street the chances are

you may hear as much German as if you were in Deutschland itself. Nor is this

all; the place is a perfect Babel. It is a pity that Flower and Dean Street

should be, as it were, representative of England and her institutions. It must

give the intelligent foreigner rather a shock.

But place aux dames is my motto, and even in the slums let woman take

the position which is her due. In the streets the ladies are not in any sense

particular, and can scream long and loudly, particularly when under the

influence of liquor. They are especially well developed as to their arms, and

can defend themselves, if that be necessary, against the rudeness or insolence

or the too- gushing affection of the other sex. As to their manners and morals,

perhaps the less said about them the better.

Let us step into one of the lodging-houses which is set apart exclusively

for their use. The charge for admission is threepence or fourpence a night, or a

little less by the week. You can have no idea of the size of one of these places

unless you enter. We will pay a visit in the afternoon, when most of the

bedrooms are empty. At the door is a box- office, as it were, for the sale of

tickets of admission. Behind extends a large room, provided at one end with

cooking apparatus and well supplied with tables and chairs, at which arc seated

a few old helpless females, who have nothing to do, and don't seem to care much

about getting out into the sun. Let us ascend under the guidance of the female

who has charge of the place, and who has to sit up till 3 A.M. to admit her fair

friends, some of whom evidently keep bad hours and are given rather too much to

the habit of what we call making a night of it. Of course most of the rooms are

unoccupied, but they are full of beds, which are placed as close together as

possible; and this is all the furniture in the room, with the exception of the

glass, without which no one, male or female, can properly perform the duties of

the toilette. One woman is already thus occupied. In another room, we catch

sight of a few still in bed, or sitting listlessly on their beds. They are

mostly youthful, and regard us from afar with natural curiosity - some actually

seeming inclined to giggle at our intrusion. As it is, we feel thankful that we

need not remain a moment in such company, and we leave them to their terrible

fate.

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... or would you like to discuss any of the history... or if you have any observations or comments... all information is always welcome so why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'In Their Shoes' Page.