James Partleton (1837-1876)

Part II

This page is a continuation of the story of James Partleton. Click here to see part I.

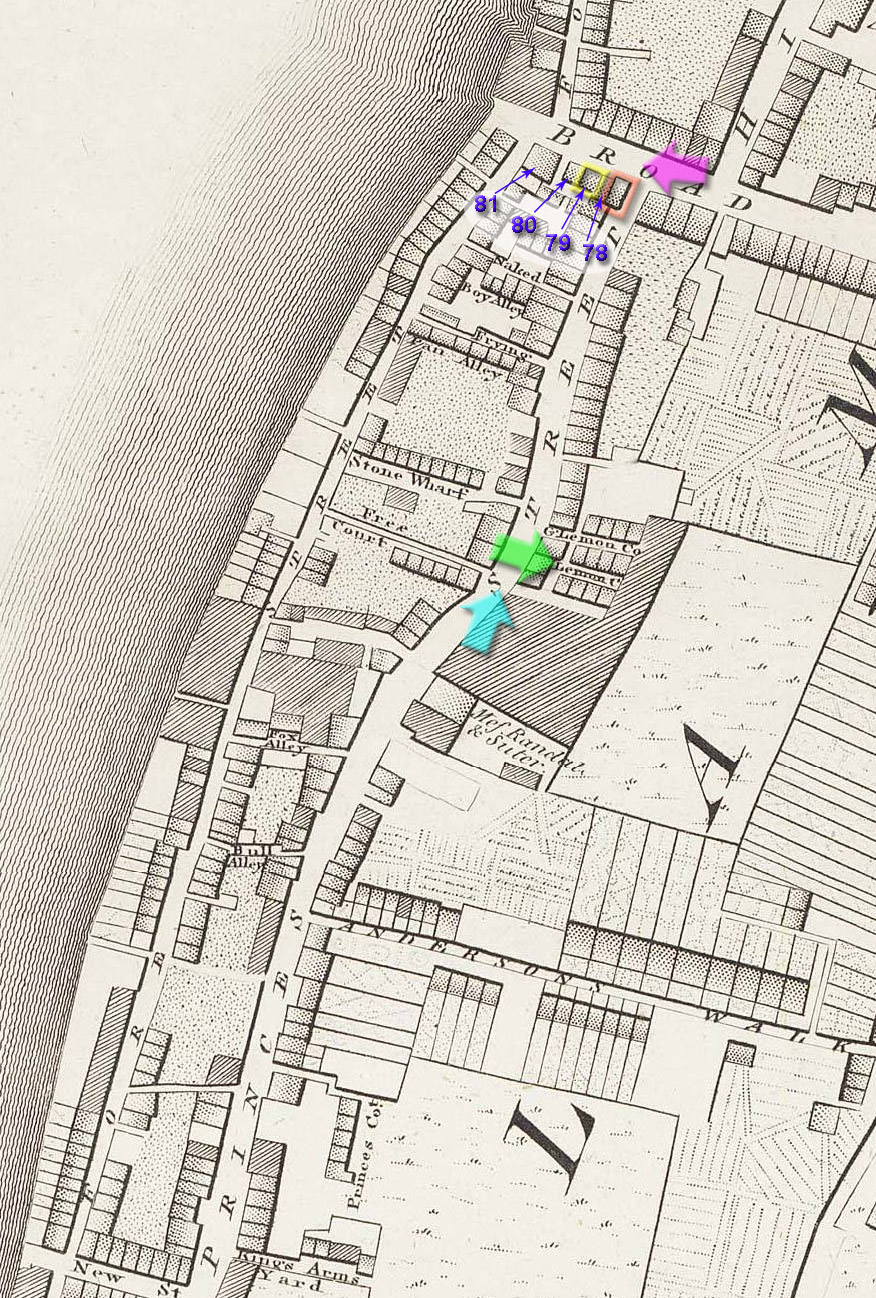

To summarise, James spent his early childhood in Drury Lane, circled blue in the map below, a lively and ancient district of London where he was surrounded by crime, prostitution, pubs, theatres, high-life, low-life, grandeur, poverty. You name it. His parents were very poor, and after at least nine years of living around Drury Lane, they decide to rejoin most of the Partleton clan who have been living, since the 1820's, south of the river in Lambeth, circled yellow:

Lambeth was of course, just another poor district of London, and James' living conditions are not going to improve. If it's possible, things are going to get worse.

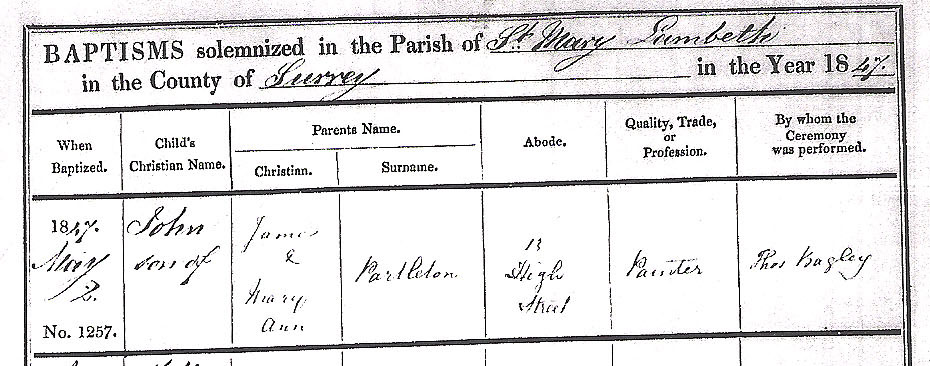

The exact date of the move must have been at some time between 18 September 1845, when James' sister Mary Ann died at Feathers Court, Drury Lane, and 02 May 1847 when his new baby brother, John, was born at 13 Lambeth High Street.

No 13 Lambeth High Street is one of the houses outlined in yellow in the map below:

By 1849, the family have moved to Dukes Head Court, otherwise known as Cockills Alley or Crookets Alley, which is how it is named in the map above, circled in blue.

We know this because James' little sister Sarah died - after 11 hours of agony - of cholera, in 1849:

Sarah was only 4 when she died, and was interred in Lambeth Burial Ground, circled in green in the map below:

She, and her big brother, our James, were drinking water contaminated by infected faeces. They were possibly drinking it straight from the Thames - and if you find that hard to swallow, don't take my word for it, read the words of the great John Snow in 1849:

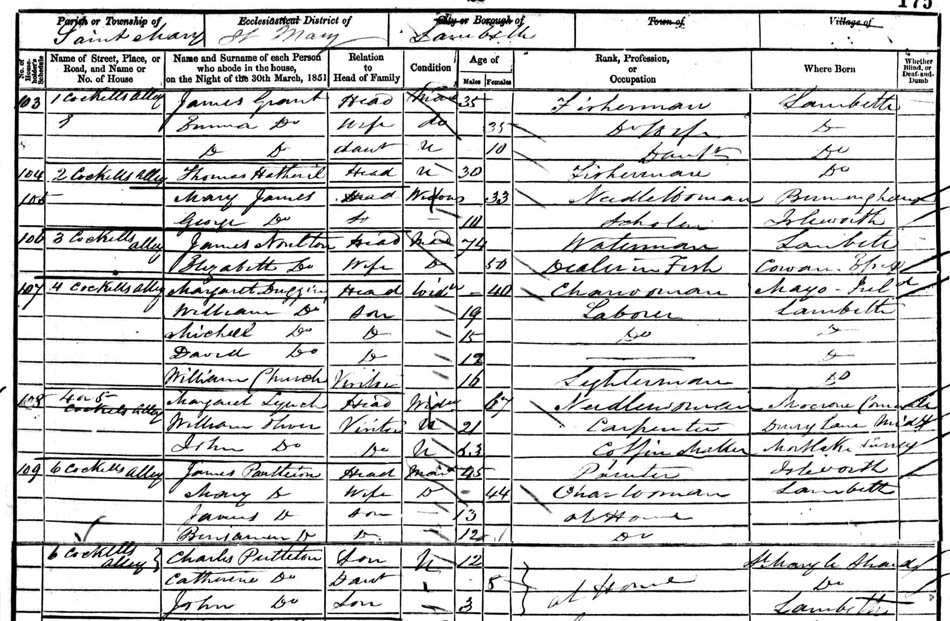

Two years later, April 1851, we find the family still resident in Crookets Alley [listed as Cockills Alley], in the UK census:

He's 'at home', aged 13, but I think perhaps it's notable that the illiterate James is not listed as a scholar. Compulsory education in Britain did not commence until the 1870's.

Until June 1851, free schooling was available at St Mary-at-Lambeth church, after which a brand-new, free, 'Ragged School' was opened to the poor, no more than 50 yards from James' house in Crookets Alley [named Duke's Head Court in the map below], along William Street, through the newly-built railway arches which now dominated the Lambeth landscape, to Doughty Street at the point of the blue arrow.

Below we see the Ragged School from the blue arrow:

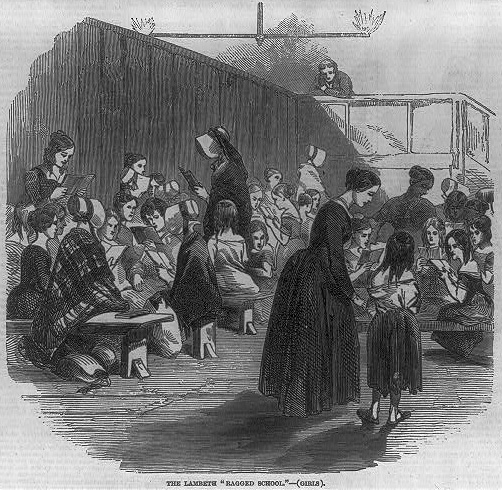

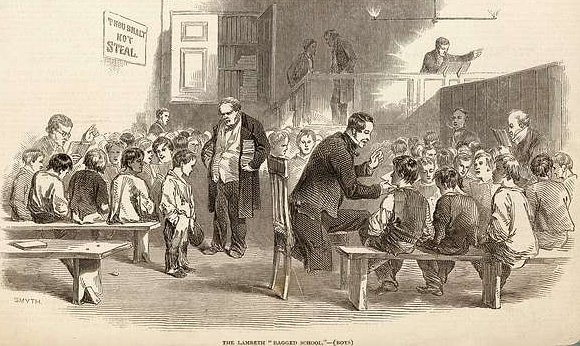

The school was paid for by charity. It consisted of just two large classrooms; one for girls and one for boys:

And we have the Illustrated London News to thank for showing us inside the school in 1851. It gives us a great chance to see how James and his siblings were dressed:

------

------

James may have attended the school; he may not. The establishment was mostly aimed at younger children, and since it is right on their doorstep, there's a distinct possibility that the younger Partleton kids were in there in the 1850's.

Social progress seems to be going backwards. James Partleton's ancestors, both men and women - going back into the 1700's - could all read and write, but James could not. He was illiterate through his life; couldn't even sign his name.

Round about the time when James was 14, in 1851, Artist J. Findlay visited Crookets Alley, for the publication "Surrey Illustrations". As a consequence we can peer through a porthole into the past and have a peek at James' House! It's one of these...

We're looking towards the High Street from the viewpoint of the blue arrow in the map below:

I think Mr Findlay used a little artistic licence to add charm to his painting.To balance this effect, here are some photographs of the immediate neighbourhood of James' home, exactly as he saw it:

These pictures are the work of photographic genius William Strudwick. The one above is taken in Lower Fore Street in 1860. We are looking north towards the church of St Mary-at-Lambeth from the viewpoint of the purple arrow in the map below:

The next photo, taken from the viewpoint of the yellow arrow, looks south down Lower Fore Street. James' House is a short distance behind the premises of Clasper, Bain & Clasper:

In the image above, we can just discern the kerbstone of Ferry Street turning to the left.

The following photograph is taken, standing in Ferry Street, looking north with St Mary-at-Lambeth church in the background:

The street we see in the above image is named Swan Yard. It's the courtyard seen, from the point of view of the red arrow, in the map below:

Three months after the census, in July 1851, James gets his final little brother, George. George is another Partleton who is to die young - but not as young as his sisters. We'll come to that in a minute.

The next we see of the family is a full ten years later, the 1861 census. James has now been living in Lambeth for 15 years. He's a 'Laborer', still living at home with mum & dad:

The above return is part of Lambeth Church First, Enumeration District 16. This is significant as we shall discover in a moment.

Here is a map which shows Enumeration District 16, which is outlined in yellow.

At the north end of the district are just four houses on Broad Street - Numbers 78, 79, 80 and 81. These are outlined in blue on the map above, but can be seen much more clearly on Richard Horwood's earlier map, upon which he outlined every house, as we see below:

And here is the point.... we have an 1864 photograph of these exact four houses, which is shown below. By the 1860's, the house outlined in red, No 77, had been demolished, probably because it obstructed the entrance to Princes Street, and as a consequence, the house next door, No 78, is supported by wooden props to save it from collapse:

So, step back in time: for here we are in 1864, looking down Broad Street towards the Thames. The immediate exit on our left is Princes Street. The turning at the left in the distance is Upper Fore Street, with the sign for Crowleys Alton Ale.

The first house on the left is No 78 Broad Street. If you check out the census sheet below, you'll see it described as a 'whitesmith' which means the owner carries out light metalwork - the opposite of a blacksmith who carries out heavy metalwork. But the owner also makes a small living by operating a small sweet shop. The proprietor is Ebenezer Parker. Now that we know this, look back at the photo above and it's obvious... it has a little Georgian shop window, and a crude shop sign tilting forward over it... what kind of sweeties could you buy for a penny?

The furthest of our block of four houses is No 81, opposite Crowleys Alton Brewery. This is recorded on the census as a pub; again, now we know this information, it's obvious. The proprietor is publican, 'Retailer of Beer', Anthony Banridge.

No 80 is unoccupied, which brings us to No 79, the home of James Partleton (1837-1876), his mum & dad, and his brothers & sisters. It's the house next to the sweet shop.

What's that outside the window upstairs? I cranked up the resolution on my scanner and we can see below, with the eye of faith, that there are flowerpots with flowers on the window ledge. Nice.

And there are a couple of likely fellows slightly obscuring our view - perhaps one of them is a Partleton... maybe it's James... indeed, why not? It's the exact right year and we're standing outside his house.

Here's another picture which would be familiar to our James; this one is one of the maze of alleys at the northern end of Upper Fore Street, near to James' house:

The above photo is unspecified; it might be Frying Pan Alley:

But the next photo, we do know for certain; it's Lemon Court, seen from the green arrow:

And to balance out the unrelenting grimness of the photographs, here's another of J. Findlay's watercolours; it's Princes Street in 1851: glimpse through a porthole into the past:

By my reckoning, Princes Street only has one dog-leg-kink in it, so our viewpoint is most likely from the turquoise arrow in the map below. That could be the entrance to Messrs Randall & Suter's starch factory, at the right of the painting.

Closer to home, for James, we get another look at Broad Street, looking east:

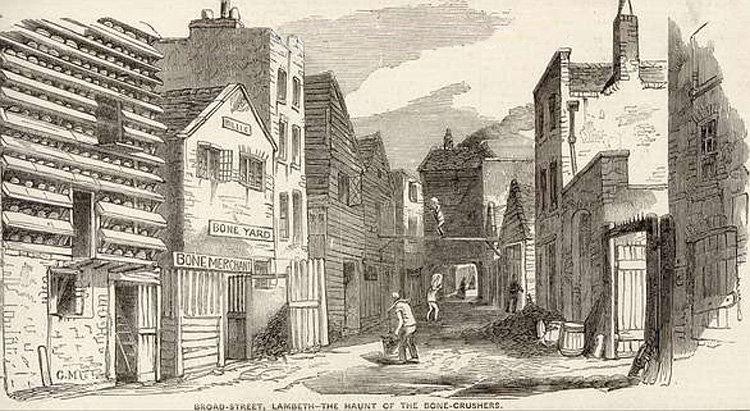

'The Haunt of the Bone-Crushers' was a Victorian newspaper's view of the rather noisome and stinky manufacturing process which was commonplace in Lambeth, crushing and boiling animal bones for the fat in their marrow, used in making candles and soap, and the bonemeal used for fertiliser. The smell was prodigiously bad, and there were constant complaints about it. Our James' house was right next to one of the biggest and stinkiest soap factories.

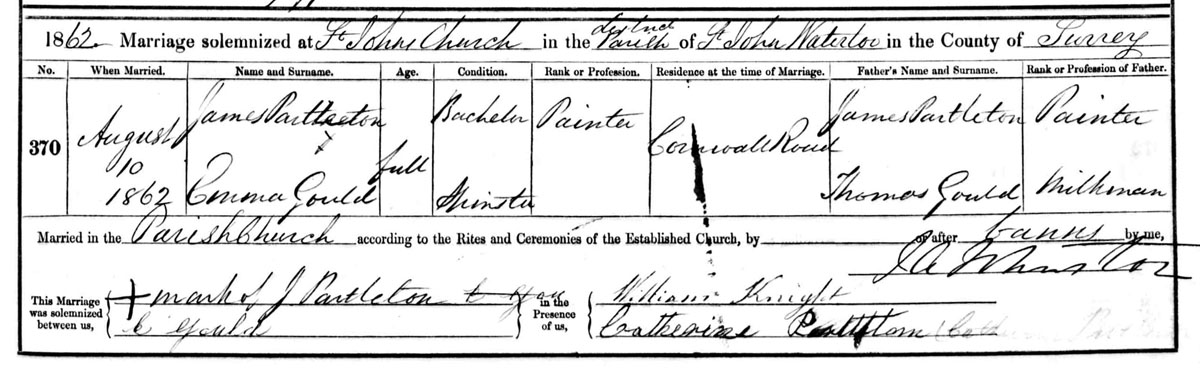

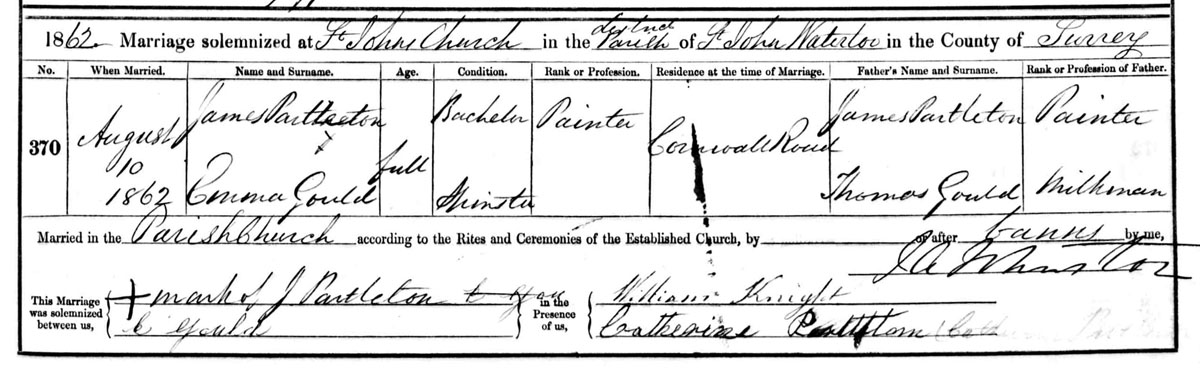

One year after the census, James is now 25, and it's time for him to get married:

We see from this certificate, signed by James with a splodge of a cross, evidence that he is illiterate. If he wants anything read, he'll have to ask his new bride - Emma Gould, who is literate, or his sister Catherine Partleton, aged 19, who witnessed the marriage and signed with the careful hand of one who is not much accustomed to writing.

Two other noteworthy points are that the vicar originally messed-up James' surname as Partington and had to correct it; not the first or the last person to make this error. He also added Catherine's name in parenthesis as she blotted the ink a little when she signed as a witness. Catherine at the time was technically a minor - adulthood was 21 - which casts a little doubt her eligibility as a witness!

James, who now gives his occupation as painter - the same as his father and his grandfather - has moved a mile or so north, to Waterloo, in the purple circle in the map below:

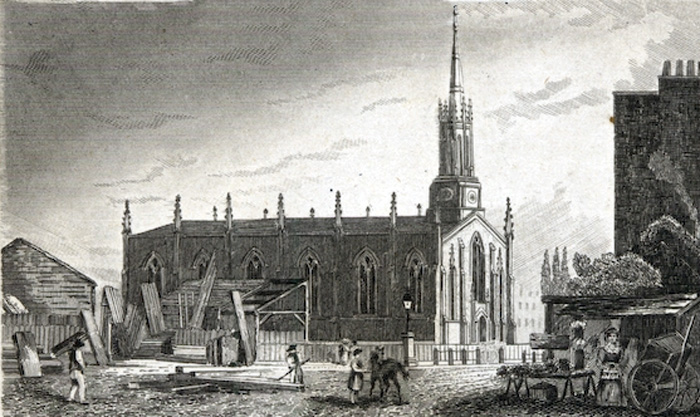

The church is St John Waterloo, which we see below soon after it was built, in 1828:

The bells of St John's are famously a little off-key, a quirk which has been retained uncorrected through the years thanks to its charm. The above view of the church is from the orange arrow in the map below:

Here's St John's in 1968, from the turquoise arrow:

In 1999, the roundabout at the left of the above picture was put to good use with the construction of the BFI IMAX theatre:

If you haven't been to the IMAX, I can recommend it. Action movies to stagger the senses. Polar Express in 3-D; beautiful. The above photo, on the right of which we still see St John's church, was taken from the viewpoint of the dark green arrow in the map below.

Here's another view of St John's, this time taken from from the pink arrow. It's a great perspective of two Thames crossings: Waterloo Bridge on the right; and Hungerford [rail] Bridge on the left.

The road bridge is not the 1817 version which our James would have seen, but its 1945 replacement - built during WW2 using mostly female labour - and if we look to its far side, it brings us directly to back to The Strand, Somerset House, and Drury Lane where James had been born. Amazingly, Waterloo Bridge was the only Thames Bridge to be damaged by bombing in WW2.

Much of the cityscape of the south bank is dominated by the two Waterloo Railway Stations and their many railway arches and bridges over the neighbouring roads. The rail bridge over the Thames which we see branching across to the left - Hungerford Bridge - leading to Charing Cross station, was not completed until 1864. In 1862 when James was married, the building project had only just started.

See the top of that tower block in the immediate left foreground of the picture above? It backs on to Cornwall Road, indeed the very same road which James gave as his home address at his wedding. We stand in Cornwall Road in the photo below and look up at the tower. What would James have made of it?

Below is a reminder of James' address:

Cornwall Road is circled blue in the map below:

Below, from the blue arrow in the map, is number 23 Cornwall Road, at its junction with Roupell Street:

The above photo was taken in 1975 - as evidenced by the No-Entry signs - but otherwise it would have looked just the same to James when he lived on the street.

Here's opposite side of the same junction, from the yellow arrow:

Here's another view of Cornwall Street:

This photograph was taken from the viewpoint of the red arrow in the map below. The year is 1936 and these buildings, which had been constructed in 1818, are about to be demolished.

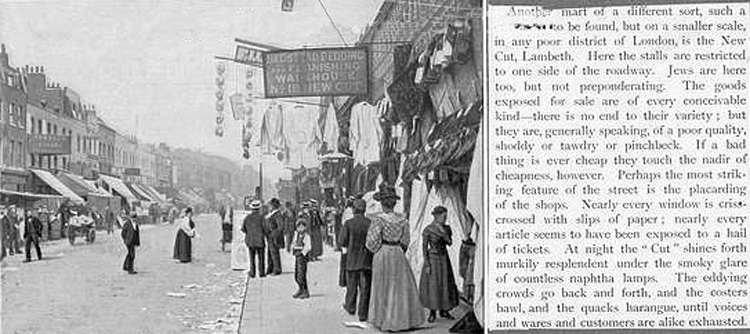

At the end of Cornwall Road, we see in the map, circled in orange, a street-market, the New Cut.

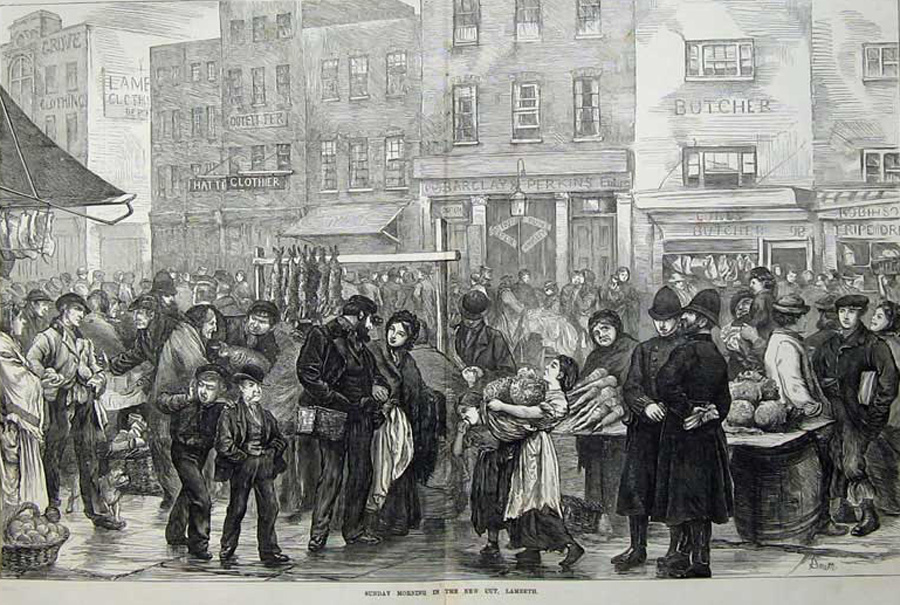

Let's step into James Partleton's working-class shoes at Christmas-time, make our way to the end of Cornwall Road, and do a bit of shopping in the New Cut:

This fiercely atmospheric, evocative print, from the Illustrated London News of 1872, by artist G Durand, titled The London Poor at their Christmas Marketing - a Sketch in the New Cut - gives us a superb insight into London life of the time when our James was an inhabitant of the metropolis. A night-time market: just look at the outdoor lighting:

It seems to be some sort of oil lamp. An open flame fed by a funnel which holds the fuel!

Some light is cast on this, if you'll excuse the pun, in a much later article, of 1901, about the New Cut:

There are a couple of things I really like about this article. One is that we see the original meanings of the words shoddy and tawdry! They were actually both nouns: types of cloth used to make low quality apparel. Hence the modern derivation of the adjectives.

The other thing is the description of the ambience of the New Cut by night, which 'shines forth murkily resplendent under the smoky glare of countless naptha lamps'.

Here's a naptha [ie paraffin/kerosene] lamp:

But this lamp of c1900 is obviously high-technology compared to the lamps which adorned the market in James' day, so let's go back to that great picture:

Walking round the chilly December market in James' shoes, our senses are bombarded: we'll hear a lot of noise, the 'bawling of the costers'; the 'harangue of the quacks'; we'll smell the smoky paraffin lamps, the produce, the fish; and we'll see the market 'shining forth' with naked flames, which look rather risky to the well-being of all those flammable materials.

Look at the woman on the right, trying on shoes, encouraged by the stallholder. Her feet are lit by a candle in a glass. There are a couple of what may be Recruiting Sergeants for the British Army amidst the crowd. It's probably difficult to avoid the attention of these chaps if you're a young man. And, by the way, a piece of advice: hang on tight to your wallet in those jostling crowds!

The next engraving is again from the Illustrated London News; again the working-classes out shopping in the New Cut:

James and Emma didn't stay in Waterloo very long, but we should take one last walk to the southern end of Cornwall Road to see another feature of the area:

We are looking straight down the New Cut from the point of view of the purple arrow in the map below:

The large building on the right of the engraving is the Royal Victoria Theatre, known to us as the Old Vic, originally called the Royal Coburg Theatre. James' dad appeared there, aged 19, and danced a Terzette Chinoise on 13 May 1825, more than a decade before baby James was born:

, Saturday, November 9, 1889 reduced versionR.png)

And that's that for Waterloo. James may not have been there very long, because his first child, John, was born in 1862. James is back in Lambeth:

Their home address is now Wickham Street, circled green below:

The baby was christened in the church of St Mary-the-Less - the first time we've seen this church in the Partleton Tree. It had been built in 1828 to help with the overflow from St Mary-at-Lambeth, hence its name of St Mary-the-Less. Below we see it, not as James did, but in 1831 when it was quite new; from the viewpoint of the orange arrow in the map above.

And 125 years later, in 1956, we see the church from almost exactly the same viewpoint, in a paper-strewn street with Teddy Boys ambling past the Funeral Directors:

St Mary-the-Less was demolished in the 1960's.

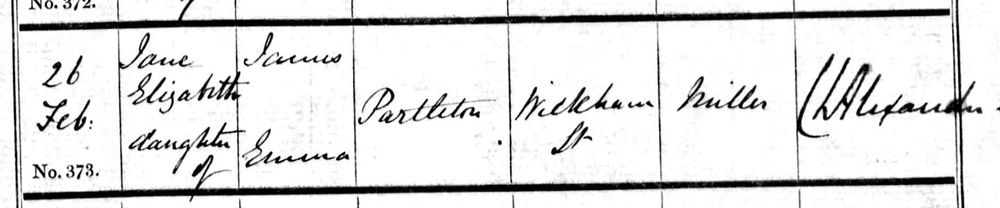

The family are to live at Wickham Street for some years. In 1864, James' next child is baptised:

Wickham Street is described by Charles Booth for his Poverty Map of London in the 1890's:

Wickham Street: 2 [stories]: poor & very poor except at south end where there is some pink [map colour for 'fairly comfortable'] : windows bad : ill-shod, dirty children.

This time, the baby is christened at the main church of St Mary-at-Lambeth.

Little Emma Elizabeth Partleton was not long for this Earth; Her death was recorded in the July quarter of 1864, aged about 1 year old; cause not known yet.

The next child is Jane Elizabeth Partleton, christened on 26 February 1865:

James is through with house-painting. For the first time, his occupation is given as Miller, which is significant.

It just happens that there is a mill very close to his house...

See the boathouse at the point of the red arrow above?

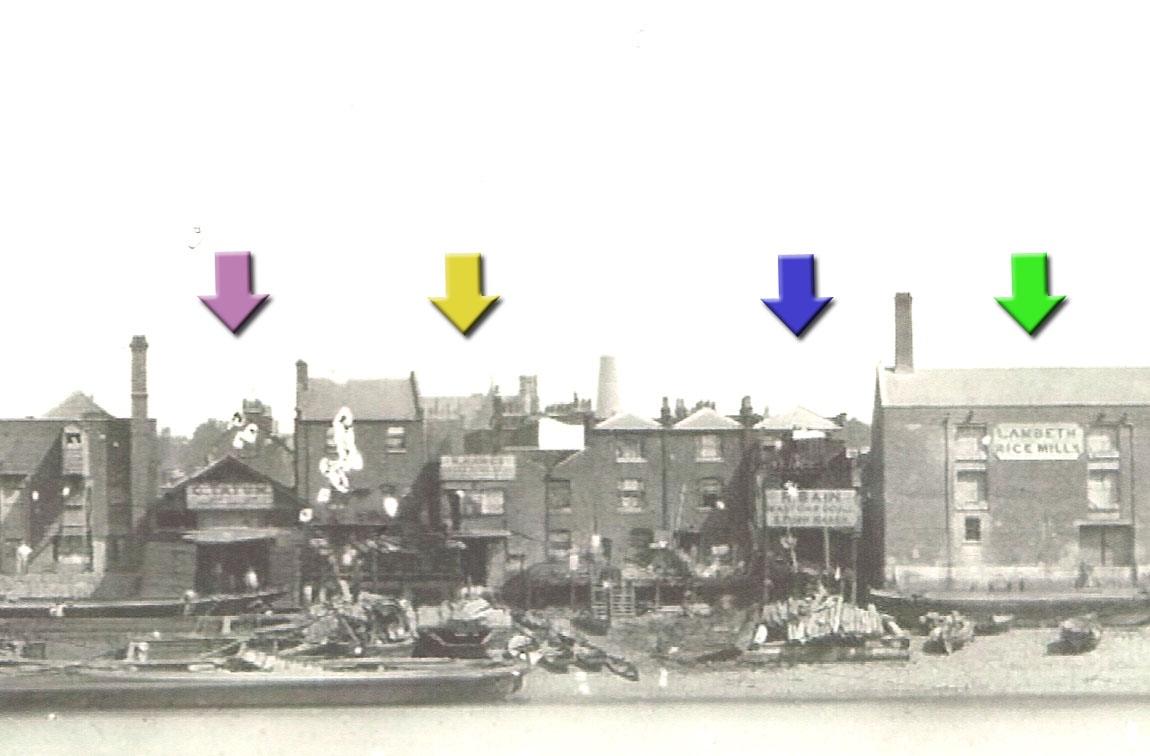

We can see the same building from the opposite side, picked out by the red arrow on the riverside in this lovely photo of the Lambeth foreshore:

Next to the red arrow is the green arrow, the Lambeth Rice Mill.

There is good evidence, which will see later, that James Partleton worked in this building. Here's a closer look:

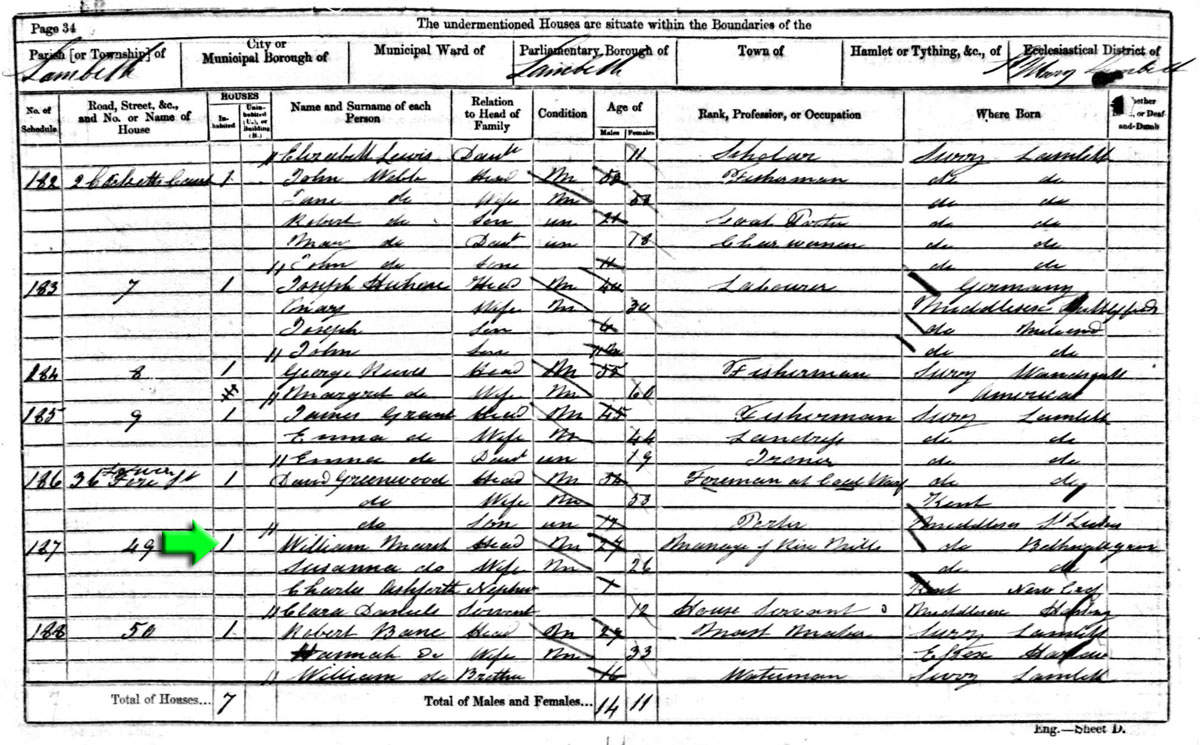

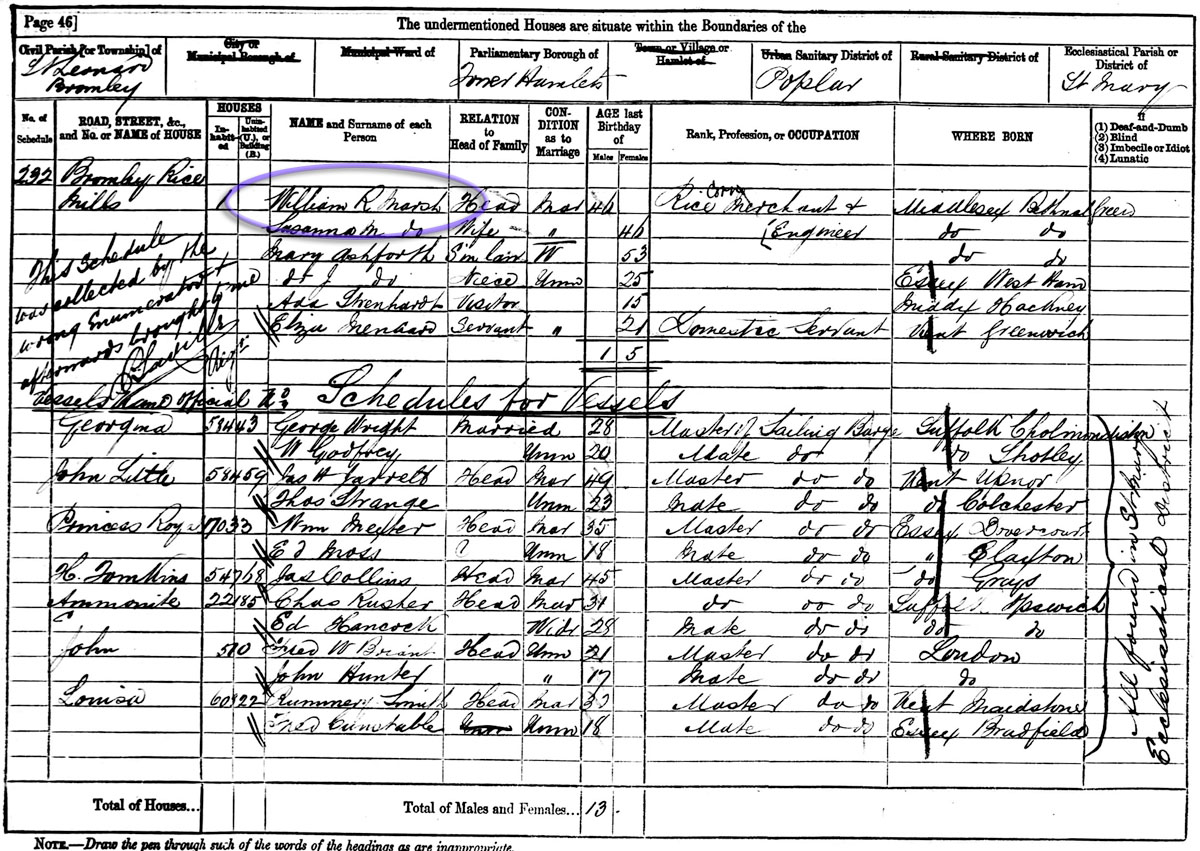

The manager of the rice mill, at No 49 Lower Fore Street, was William Marsh as we see in the 1861 census. We'll also see him again later:

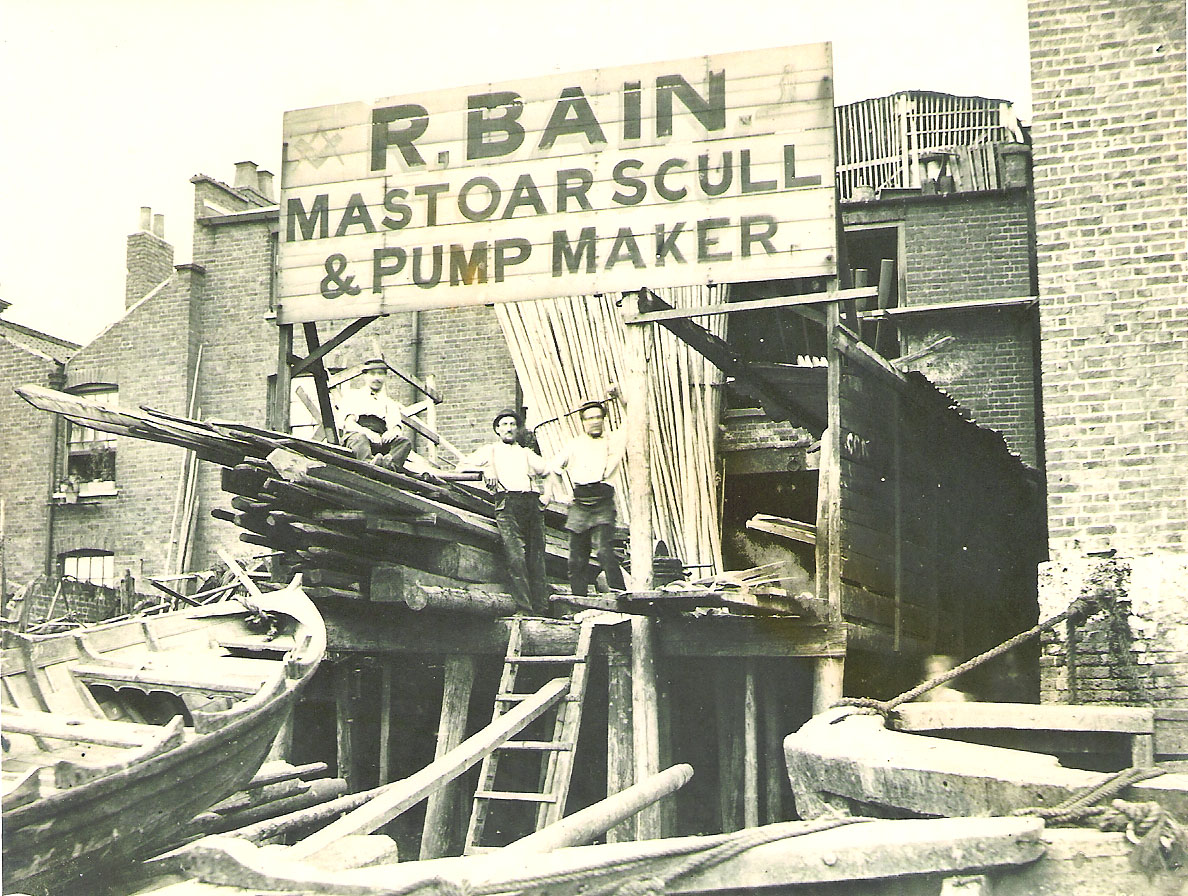

And this is too good an opportunity to miss to publish the next photo: the premises right next door to the Rice Mill, Robert Bain's boat yard:

In the above photo, the brick building on the right is the Lambeth Rice Mill, with barges tethered to it. James, a labourer in the mill, would be extremely familiar with this view.

The babies in Lambeth are coming thick and fast. The next is Emily Bertha, baptised on 15 July 1866:

The case of Emily Partleton is unusual, because fate has preserved for us her image.

The credit for unearthing this wonderful chunk of historical evidence goes to Brenda Callaghan, a descendant of James Partleton, who undertook a fabulous piece of research to obtain information of great interest to this web page. But we are getting ahead of ourselves. We'll come to that later.

During 1867, the family moved north of the river:

Why did they move? Well, again, on this website we sometimes see people in the Victorian era upping-sticks and moving house to the other side of London, and we never know why they did it; it all looks very random from such a distance in time. But in the case of our James, we do know. The place where James worked as a miller closed in Lambeth and relocated to the East End of London, and James followed. And when you think about it, it's obvious: that's probably the reason in 99% of cases. They weren't moving house for leisure or for pleasure; they were simply following the work.

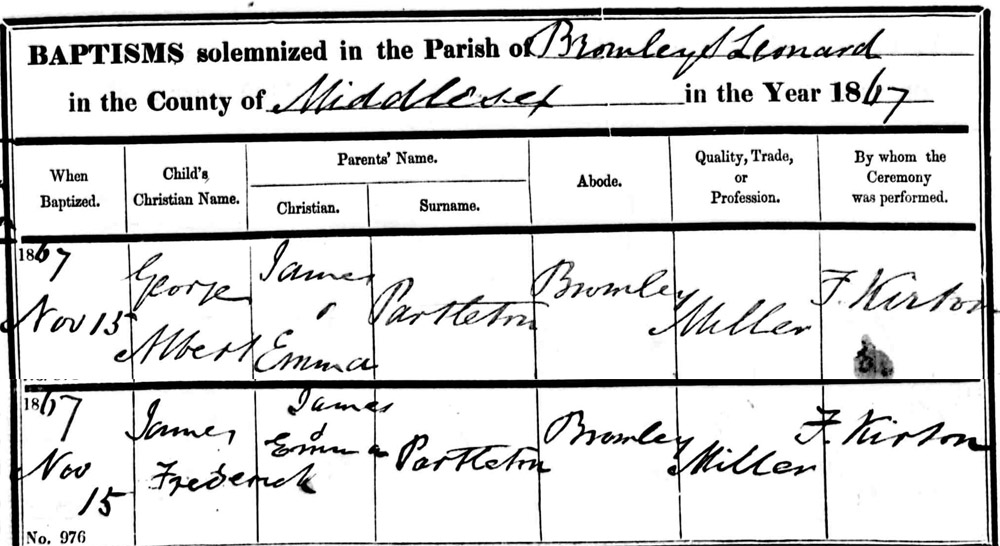

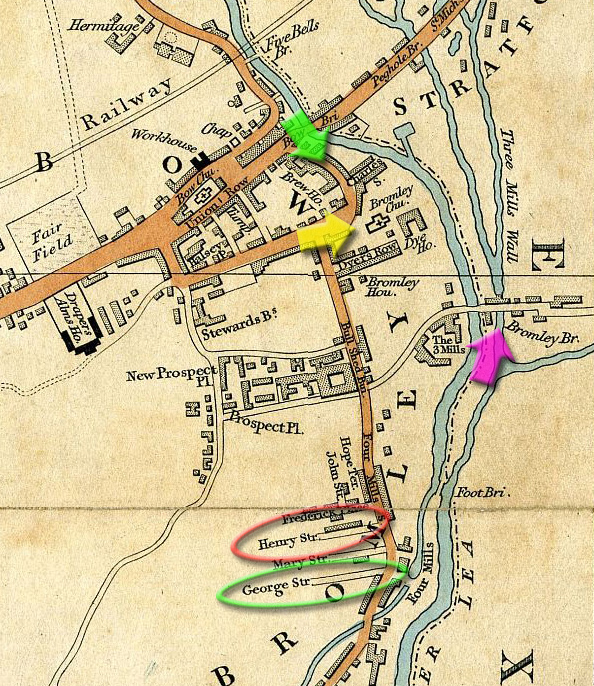

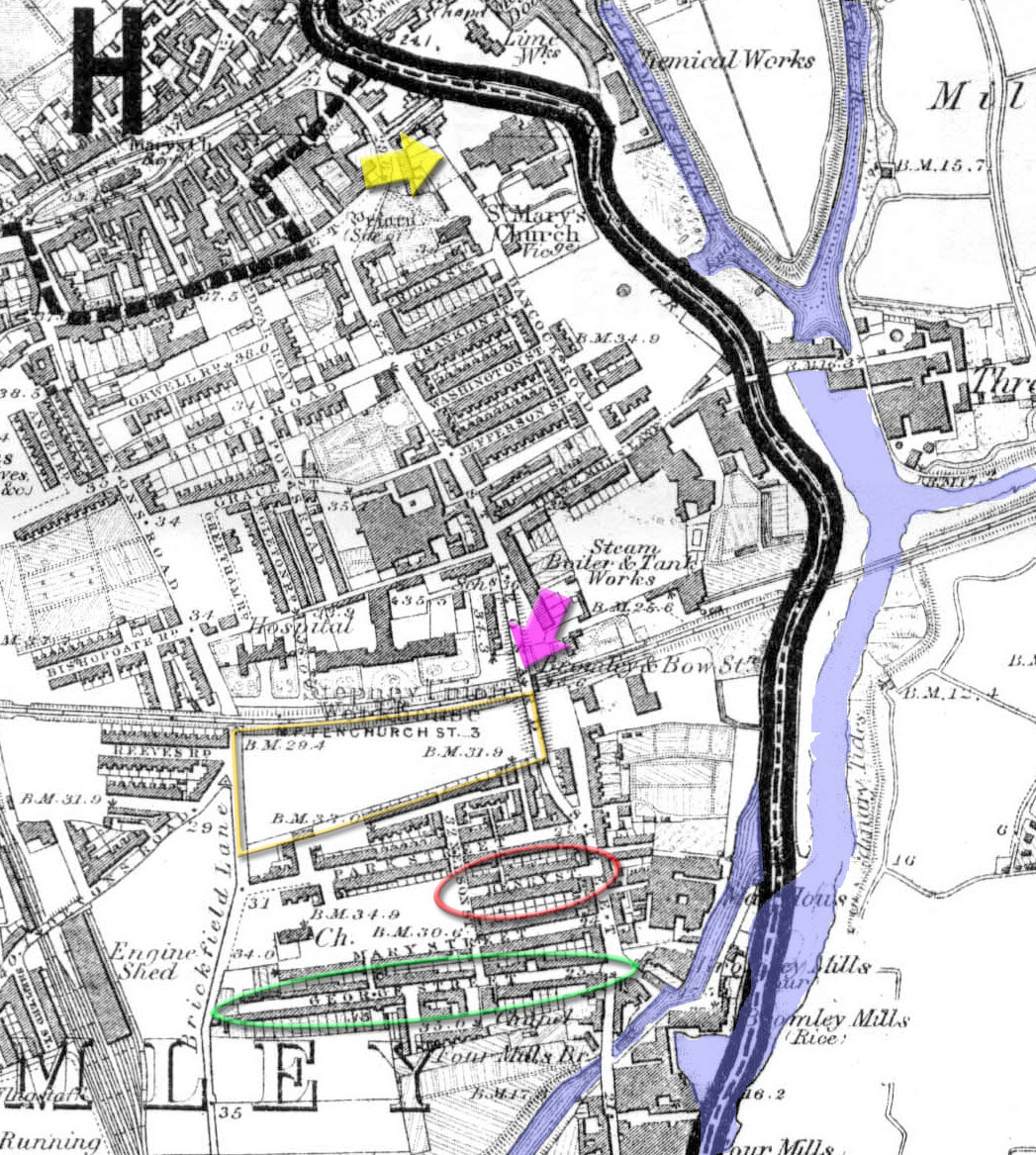

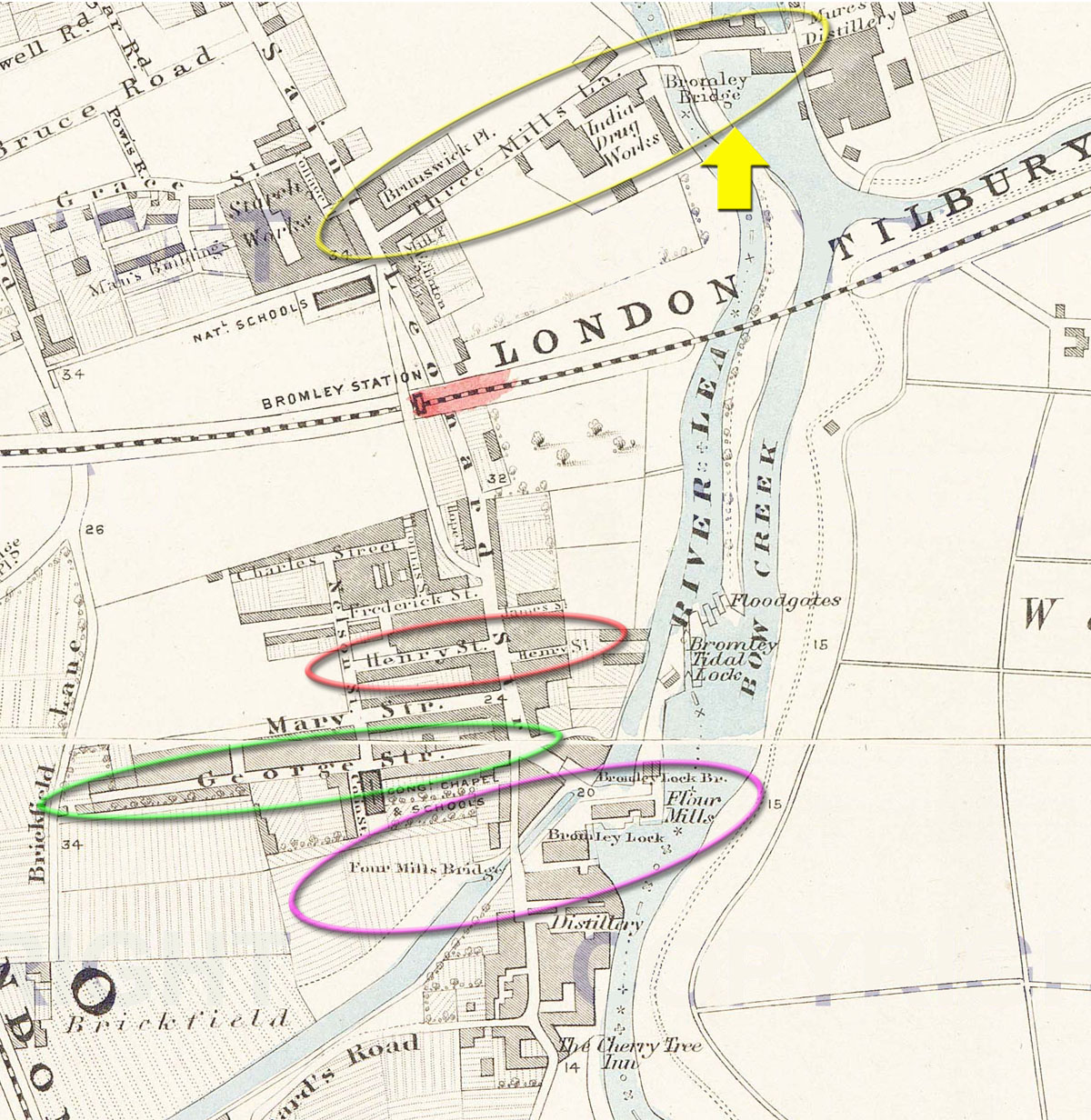

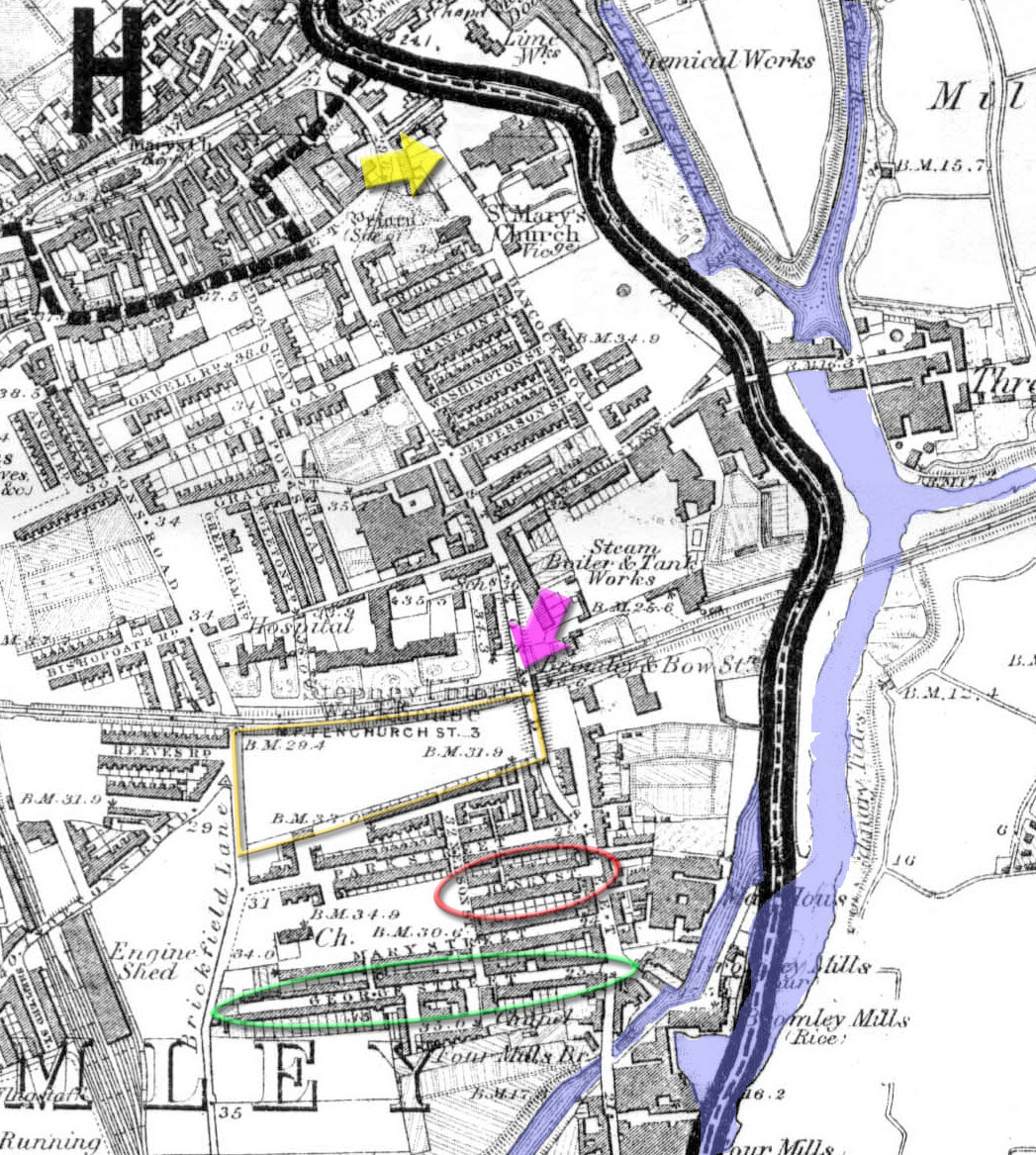

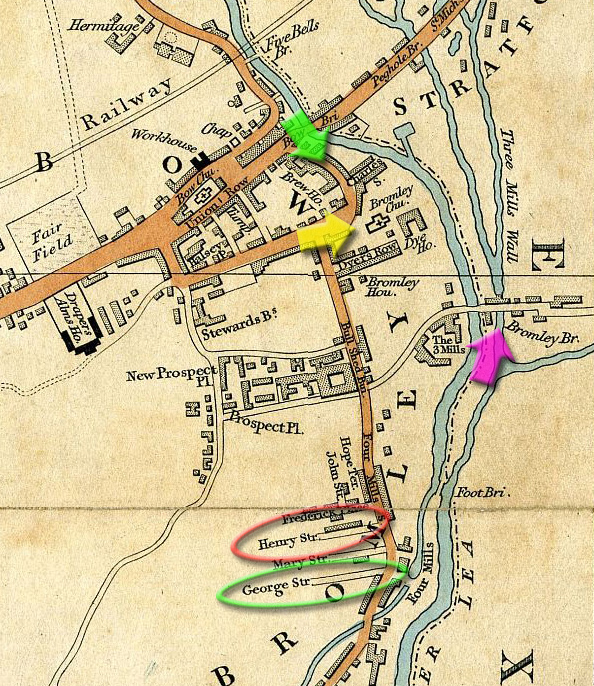

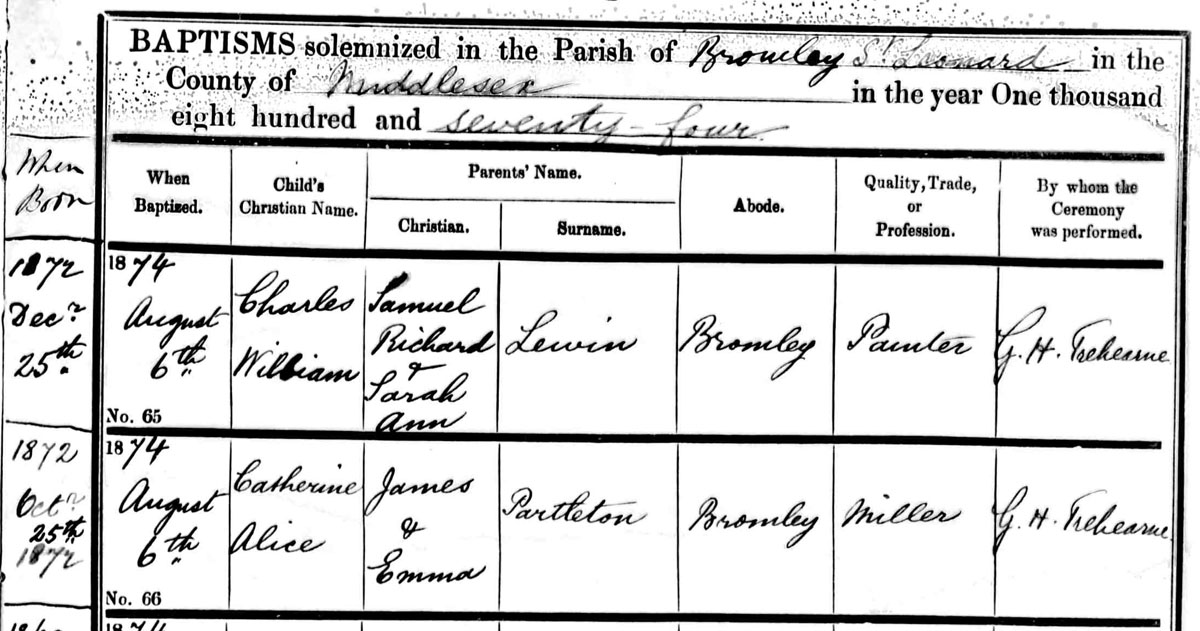

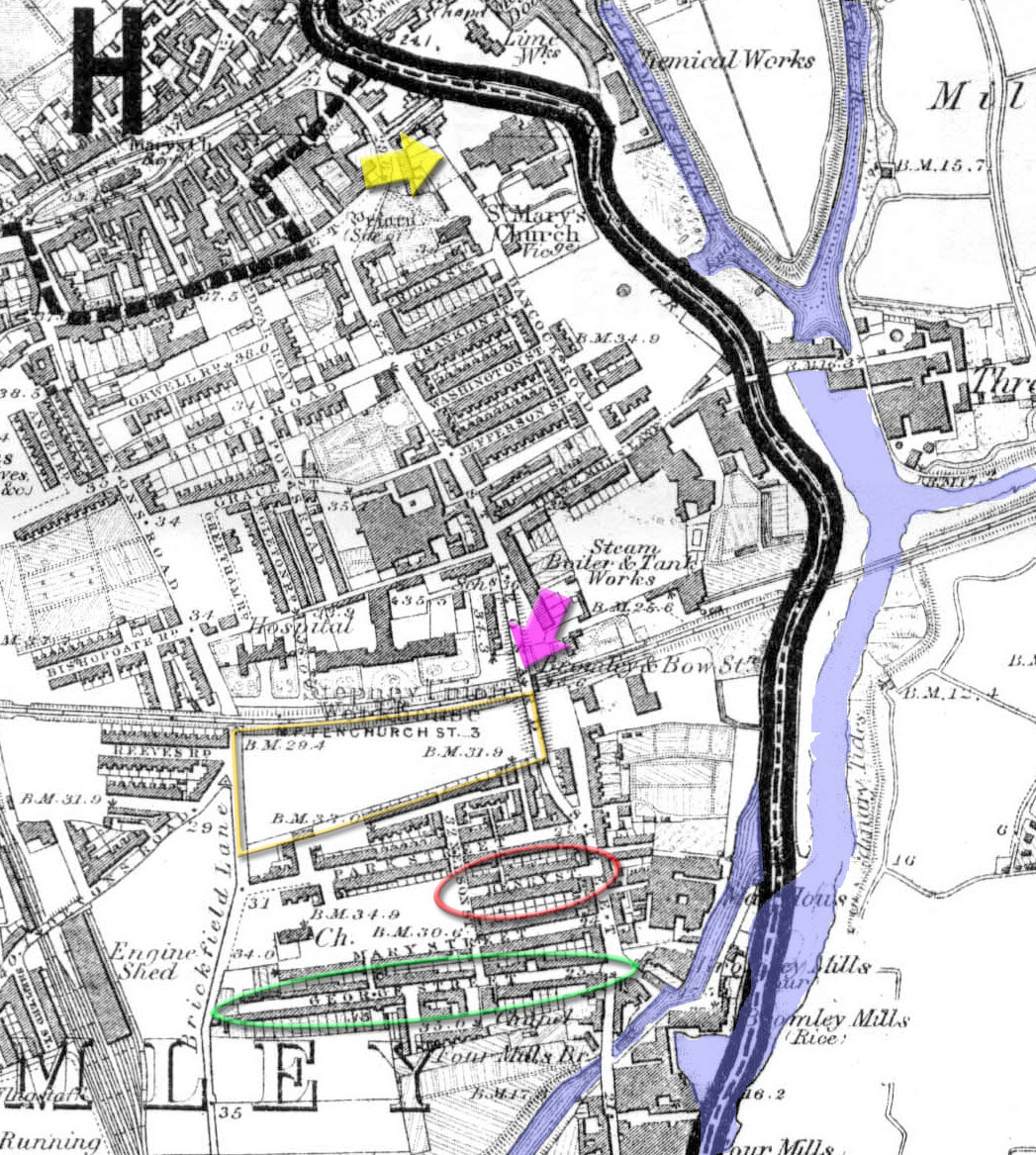

The two twin boys in the parish register above, George and Frederick, were christened on the same day at the church of Bromley St Leonard. "Where is Bromley St Leonard?", I hear you ask, and I can tell you, it took me quite a while to untangle their new location.

The map above is John Cary's of 1818, and it shows us the position of the church, which is in a place called Bromley-by-Bow, in the red circle. In the present day, Bromley-by-Bow is so deeply embedded in the vast urban and industrial sprawl of London that it's difficult for us to envisage that what's happened to James and his family is that they have left London and are living in the countryside.

Here's an early view of the church of Bromley St Leonard, with the River Lea in the background behind it. The artist is H Jones. This is where baby George and baby Frederick were baptised, and may be where baby George was buried six months later:

75 years later, during WW2, St Leonard's church suffered a direct hit from a bomb and was completely destroyed. But we still know what it looked like to James and Emma, because the interior was captured in c1850 by artist George Hawkins and in a later photograph:

iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii

iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii

We can see it clearly, at the point of the yellow arrow, in this detailed view of the 1837 edition of Cary's map:

And here's Bromley-by-Bow High Street, as James would have seen it. From the curvature of the kerbstone, we may be looking from the viewpoint of the green arrow in the map above:

I've read online that the remaining ruins of St Leonards church were obliterated by the building of the Blackwall Tunnel Approach Road in 1969, but as you can see from the modern map which I have overlaid, the new road missed the church completely:

The remains of St Leonards church and possibly the graves of several of James Partleton's children, not to mention James himself, actually lie underneath the warehouse circled in blue in the satellite view below:

Here's the warehouse, seen from the Blackwall Tunnel Approach Road, picked out by the blue arrow in the photo below:

Frankly, ill-health and short lives seems to haunt the family, as we shall see. Baby George lived less than a year. His twin brother Frederick lived to adulthood but died in 1908 aged 41.

In December 1868, James Partleton gets another new son, Henry Albert Partleton. Unfortunately, little Henry died in the January quarter of 1869.

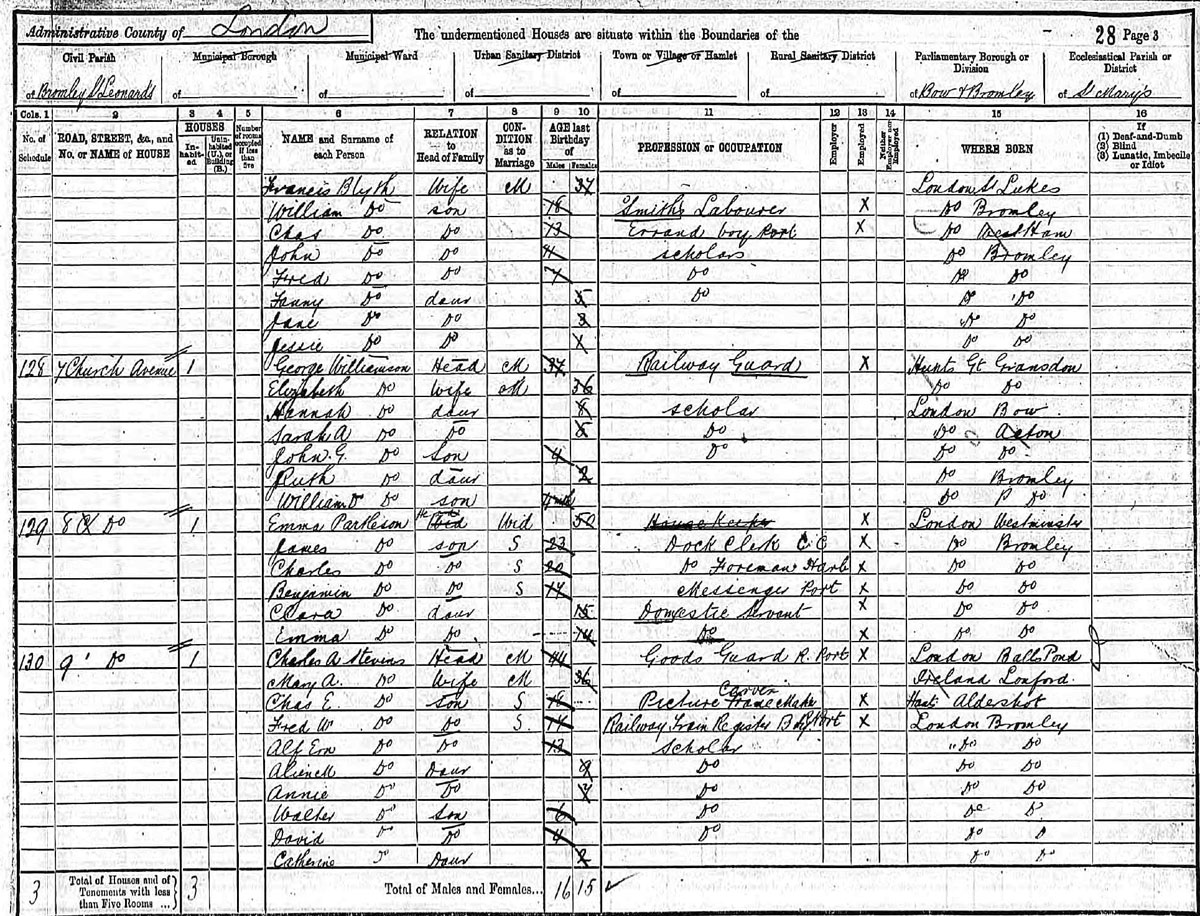

The next document shows the whole family together in the census of 1871:

As we see above, Charles and Emma have a new baby - Charles, who had been born on 28 June 1870. Charles died in 1907 aged just 37.

Their address is George Street, Bromley-by-Bow, which is circled in green in the map below [and in all our maps of Bromley]:

We can have a look at their local station (built 1858) from the viewpoint of the purple arrow in the map above.

It's labelled Bromley & Bow in the Victorian map, spent most of its life being called just Bromley, but was was renamed Bromley-by-Bow in 1967 to avoid confusion with the larger town of Bromley in South London.

The above photo is from 1956; the Victorian frontage is now gone as we see in the 1971 photo below:

As if to establish our Partleton family's new East End credentials, if you ever get a close-up glimpse of the fictional tube map in BBC's Eastenders, Walford East station is placed at the location of Bromley-by-Bow.

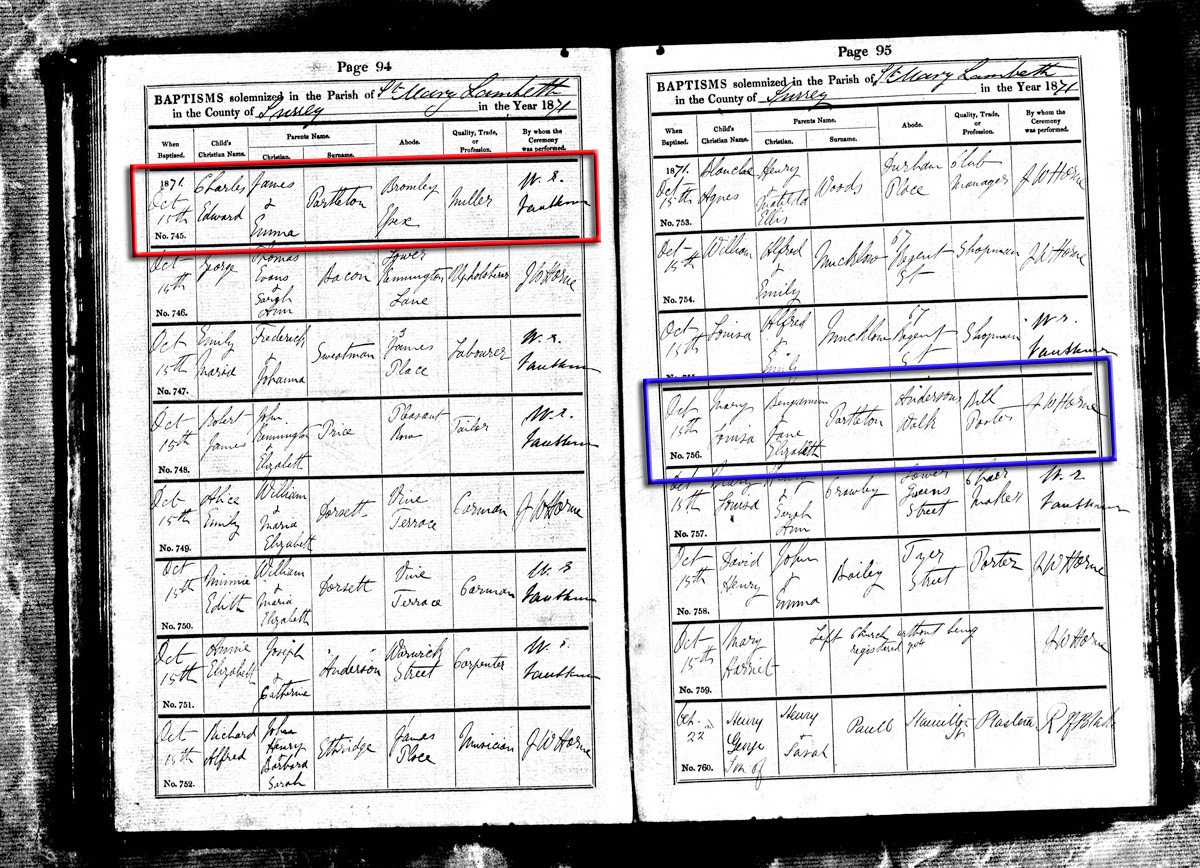

In October 1871, there seems to be a bit of a family get-together. James travels back across London to be with his brother Benjamin, and they have James' new son - Charles, and Benjamin's new daughter - Mary Louisa, baptised on the same day in the church of St Mary-at-Lambeth.

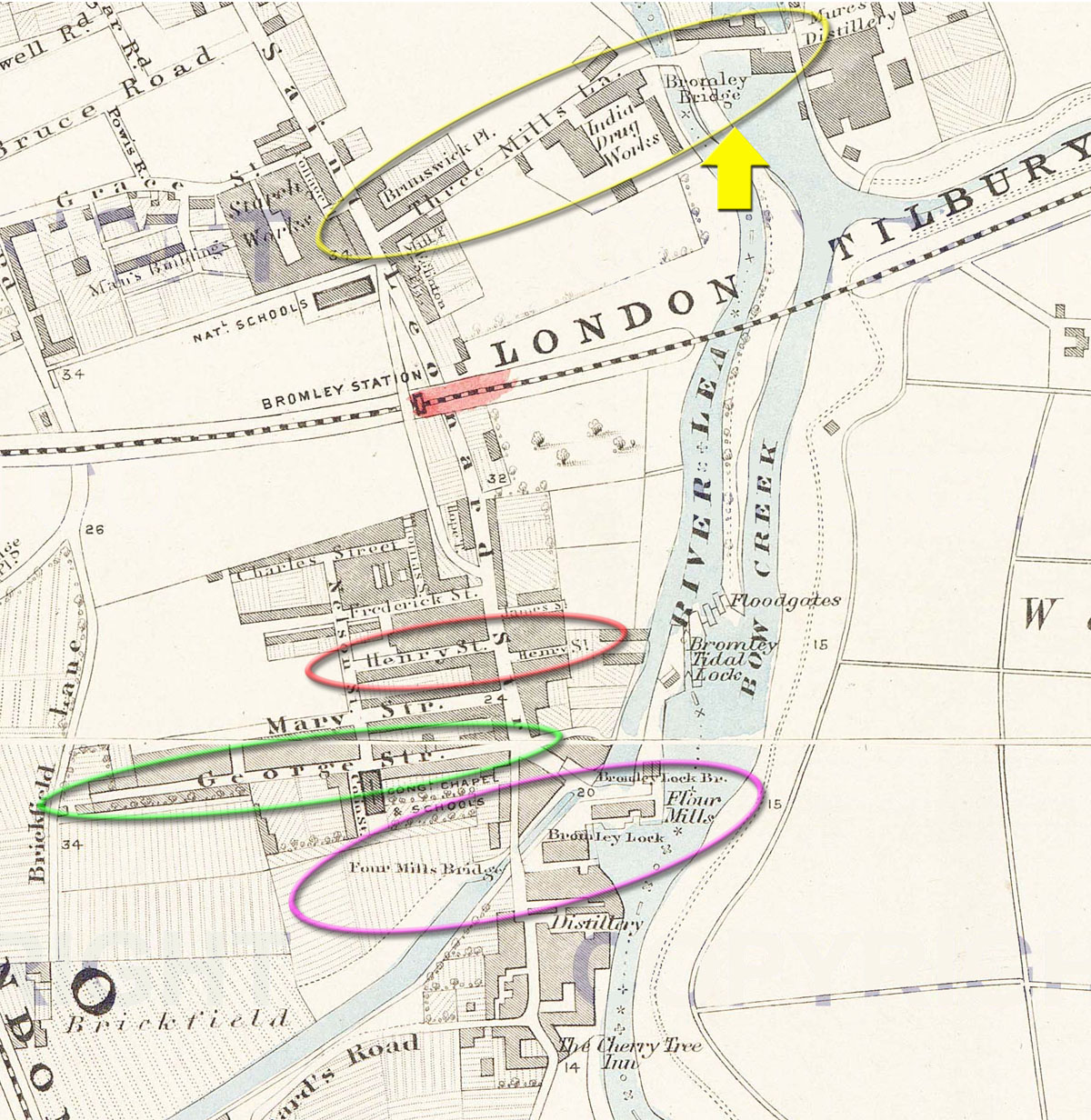

Since James continues to be recorded as a miller, we can bring absolute clarity with another of our Victorian maps of Bromley-by-Bow. This one is Stanford's map of c1863:

James Partleton's house, in the green circle, is right on the doorstep of The Four Mills, circled purple. The river Lea is highly tidal; the mill-locks trap vast quantities of water raised by the tide, using a system of lock gates, and then allow it to flow back downstream to drive their water wheels.

James is actually employed as a rice-cleaner - whatever that is. And if we look at this c1861 map of Bromley-by-Bow, we see, at the bottom of the map, that the Four Mills are partly rice mills, just as the mill at Lambeth had been:

Accommodation in George Street and Henry Street is probably provided as a part of the job - at a cost. No doubt, it's far better than the slum housing in which James grew up. He's working hard and making progress in life.

There's nothing left of The Four Mills, but if you look a little further north in the maps, you'll also see The Three Mills.

The 18th-century buildings of the Three Mills, located in the vicinity of the purple arrow in the map above, would be wholly familiar to our James, and they still survive today. Below we see them from the point of view of the purple arrow in the map:

Here are some of the surviving giant millstones inside these buildings:

Milling corn seems to be a wholesome business, but, as is clear in the 1860's map below, both of the mill complexes have large distilleries attached to them. Most of the grain is used to make booze.

The Bromley distilleries are major contributors to the gin-drinking culture which held London in it's grip for decades.

As for James' house of 1874, we see it in the green circle above and below, with its old name of George Street and its modern name of Empson Street:

Google Street View allows us to see what has become of the area, seen from the purple arrow in the map above. The first building on the left is in Empson Street, formerly George Street:

There's nothing left of the original Georgian buildings of Henry Street and George Street. The eastern ends of these streets lie under the carriageway of the 1969 roadway, and by my reckoning, the apartment blocks on the left, which now occupy the rest of the site, were built soon after the road, in the early 1970's.

Before we move on, we have some clues as to the reason for James' relocation to Bromley-by-Bow. You may remember earlier on this page, we identified the Lambeth Rice Mill:

James' departure from Lambeth to Bromley in 1867 was surely not just coincidence, because this is the year that the Albert Embankment came to the south bank of the river Thames.

The rice mill is on the right in the middle-distance of the above photo, which was taken in 1867. What is obvious is that barges will no longer have access to the mill; the new embankment and road are in the way. The mill would have to close.

You may also remember that we identified the manager of the Lambeth Rice Mill - William Marsh. In the 1871 and 1881 censuses, we search for him, and find him... in Bromley-by-Bow:

It seems that our James has gone with his boss to the new location of the business.

For James and Emma, the babies keep coming. In July 1874, they christen their last little boy, Benjamin George:

And surprisingly, a month later, they christen their daughter Catherine Alice "Kate", who had been born two years earlier. You'd have thought they would have done it on the same day as baby Benjamin:

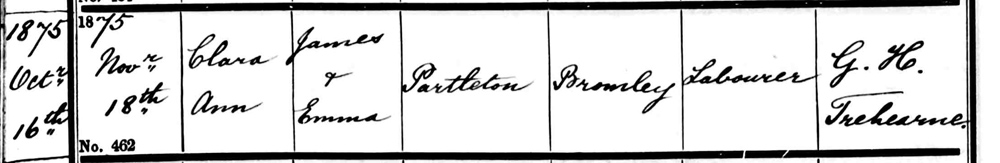

In 1875 James and Emma produce another child, Clara Ann:

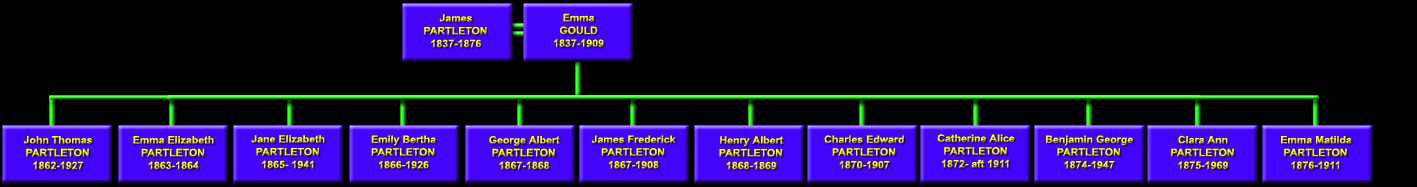

Since Clara Ann is their penultimate child, we should have a look at the family of James Partleton and Emma Gould:

All in all, as the new year of 1876 progressed, James was probably reasonably satisfied with his lot. Eight of his eleven children are still alive - par for the course for a Victorian working-class family - even if some of them are suffering from poor health, and in the latter part of the year, there's another new baby on the way. He has a steady job, and he's improved his place in the world.

But all is not well with our James. His own health is very poor.

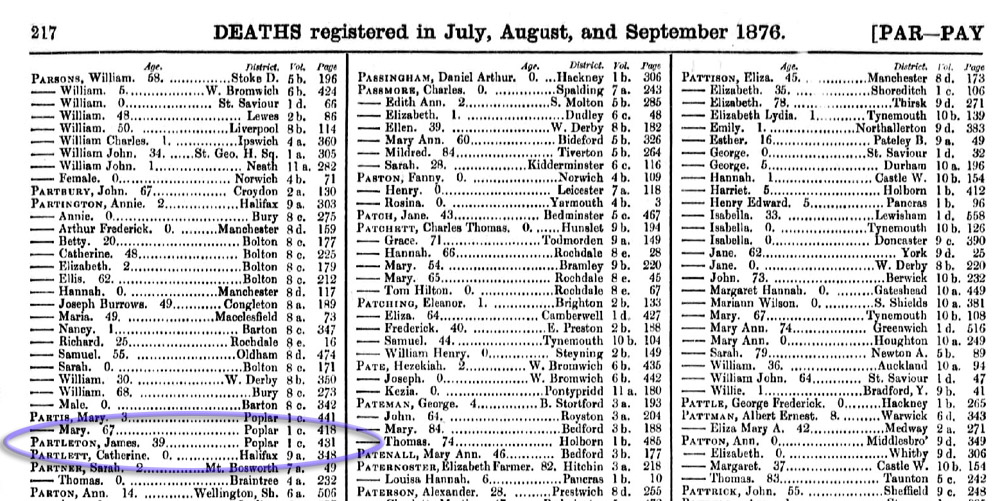

It may or may not have been a big shock to his family: James Partleton died in 1876, aged just 39:

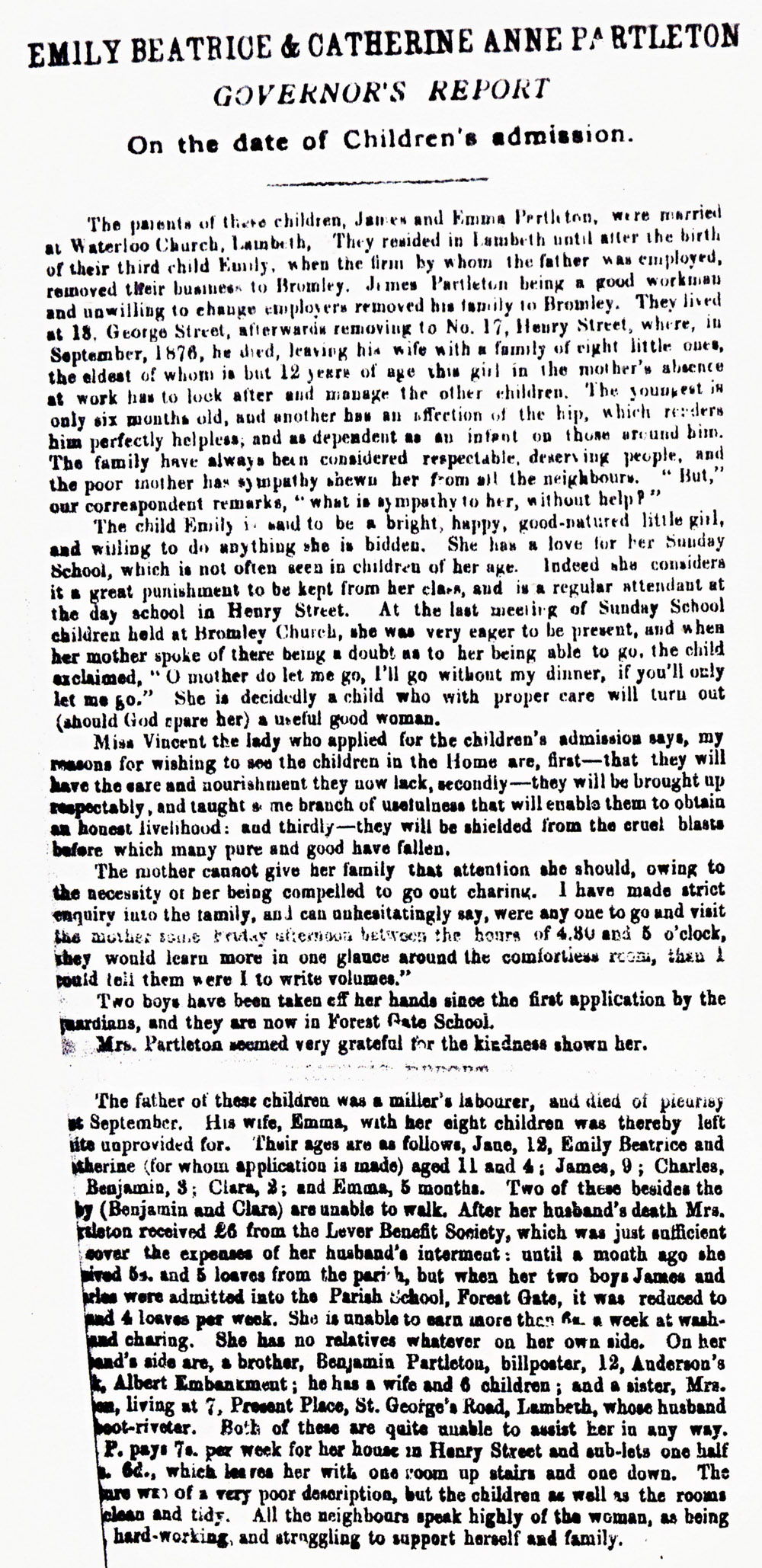

James' unfortunate widow Emma, who has given birth to 11 children in 14 years, and who is pregnant with her twelfth, finds herself fending for eight living children aged 1 to 14; her only source of income is what she earns by doing laundry and 'charing' - meaning she is employed as a cleaning-lady. This amounts to 6 shillings a week. Her rent alone is 7 shillings.

This is the age before the Welfare State, but Emma does receive some money from the charity of Victorian philanthropist William Hesketh Lever:

William was founder of the Lever Bros soap manufacturing company, which has grown to be one of the world's biggest corporations, now called Unilever. His charity donated £6 [about 5 months' wages] to Emma in her hardship, but she has a funeral to pay for, and this is where this money goes.

Emma also receives 5 shillings a week and some food from the parish. It's still not enough.

About five months after James' death, Emma gives birth to his, and her, final child, Emma Matilda:

The baby is incorrectly recorded as Partington... again, not the first time, or the last time, that this is to happen. Touchingly, James is posthumously recognised as the father.

Emma's eldest daughter, Jane - only 11 when her daddy died - is roped into the job of looking after the other children, becoming the stand-in mum while Emma went out to work.

The following photo is probably Jane in later life, in her 30's:

But there's absolutely no way Emma can earn enough money to support all those children...

Her only option is to place some of her kids into childrens' homes.

Consequently, one year later we see Emily Partleton, aged 11, clutching the hand of her little sister Kate, aged 4, photographed on their admittance into the first-ever Barnado's Home for girls. Toddler Kate is struggling to comprehend what's happening, but Emily clearly does understand. If this photo doesn't break your heart, then you're a harder man than I:

We look into the eyes of two little girls whose daddy has died, about to be separated from their mum. They are facing the terrifying prospect of a vast step into the unknown; entry into a Victorian childrens' home:

Here's the very thorough report prepared for their entry into the institution. A gold-mine of information:

Thanks again, from the Partleton Tree to Brenda Callaghan for obtaining this document.

Actually, through all this disaster, the girls have at least the consolation that they are entering what was arguably the best childrens' home in Britain, though they may not know it:

These houses were specially built for the Village Home, created by the Barnado organisation for 'Orphan, Destitute and Neglected Girls', at Barkingside to the east of London. As you can see above, it can't have been cheap to create, and by a small stroke of genius was deliberately shaped in the form of a village. You'll read more about this in the Partleton Tree web pages for Kate and Emily as we follow their fortunes into their unknown future.

Above we see, at a later date, some girls at the Village Home on a fete day, dancing for the visitors, and below we see children outside receiving some instruction, perhaps 20 years after our Emily and Kate had left the home:

And below, perhaps a couple of years further on, we see older girls receiving training in domestic service:

Kate and Emily's brothers were not quite so lucky. They went into a much more typical - and surely less compassionate - Victorian institution. James (9), Charles (6) and eventually baby Benjamin (2) - who can't walk - were taken into the 'Forest Gate District School', a welfare establishment at West Ham, providing education and residential boarding to pauper children. Below is a photo of how it looks today:

We follow the fortunes of these three boys in the own web pages on the Partleton Tree.

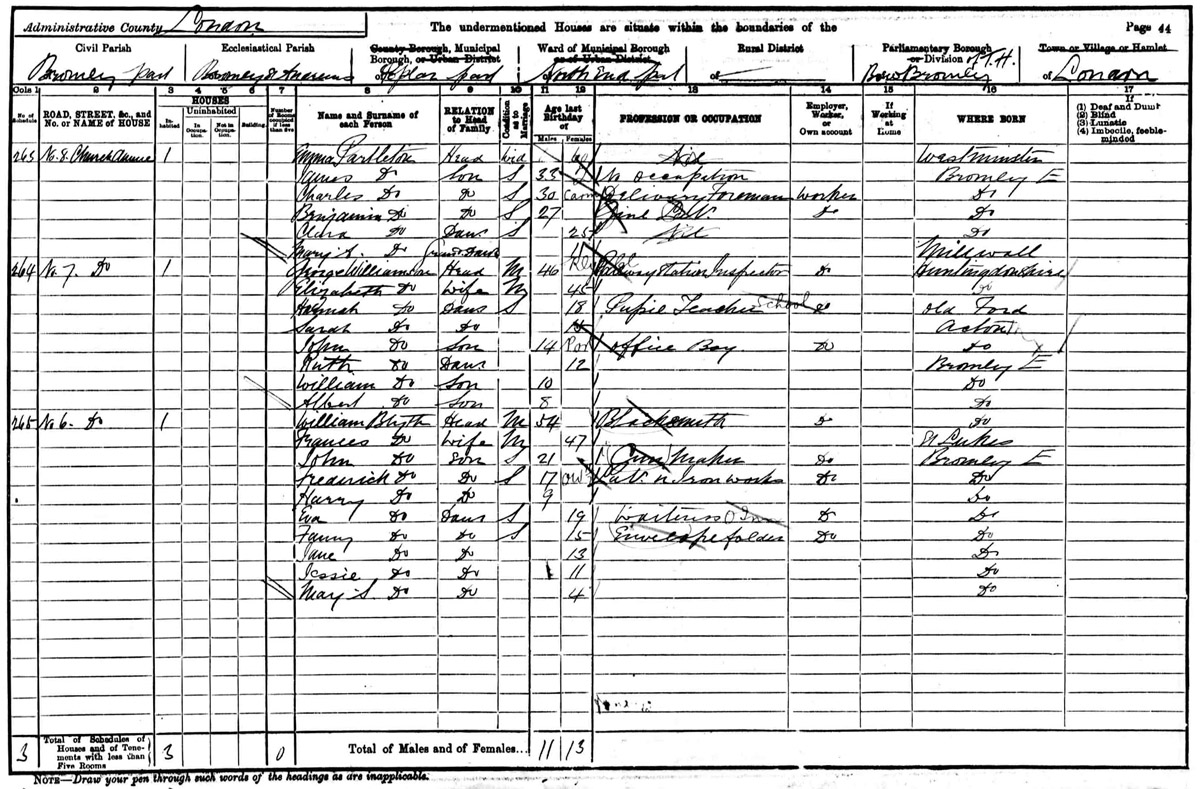

Five years after James' death, we can seek his shattered family in the 1881 census:

As we can see above, all three boys and both girls are still in their orphanages. Emma Partleton’s eldest son John is working and has his own family by now. But mum Emma, her eldest daughter Jane, and her two youngest children are missing from the census.

I say 'missing' because I’ve left no stone unturned searching for them and exhausted every path. Clearly, mother, daughter and two toddlers are all together somewhere. If anyone would like to have a shot at finding them, please do so: I’d love to know the answer to this puzzle.

Just for the record, they're not in George Street or Henry Street where they had lived before James died, or in Church Avenue, where the family lived in later years. And they're not in the Bromley Workhouse aka the Stepney Union Workhouse.

So, we move on to the census of 1891:

We see 'Emma Partleson' and her sons reunited. When did the boys come home? We don't know, but they spent at least four years in the orphanage, probably much more. The situation has changed, the boys are now young men and are all working in the nearby river port on the River Lea. Emma's two baby girls, Clara and Emma, are all grown up and are now in domestic service. With six incomes, however meagre, there surely won't be any money-troubles for the time being.

Emma's eldest daughter, Jane, now 26, has struck off on her own and is also in domestic service, back in Lambeth. And eldest son John is long married with a family of his own in Poplar.

"But what of Emily and Kate, the two little waifs in the Village Home?", I hear you say. Well, as we see in the two photographs of Emily below, Barnado's clearly groomed them for domestic service:

--------

--------

Above we see Emily Partleton upon entry, and - some years later - upon departure from the Village Home. Poignantly, Emily is all dressed up in her housemaid's outfit, and she probably wore it for her first job, where we see her below in the 1891 census in the leafy South London suburb of Upper Norwood.

Barnado's have obviously taught her how to cook:

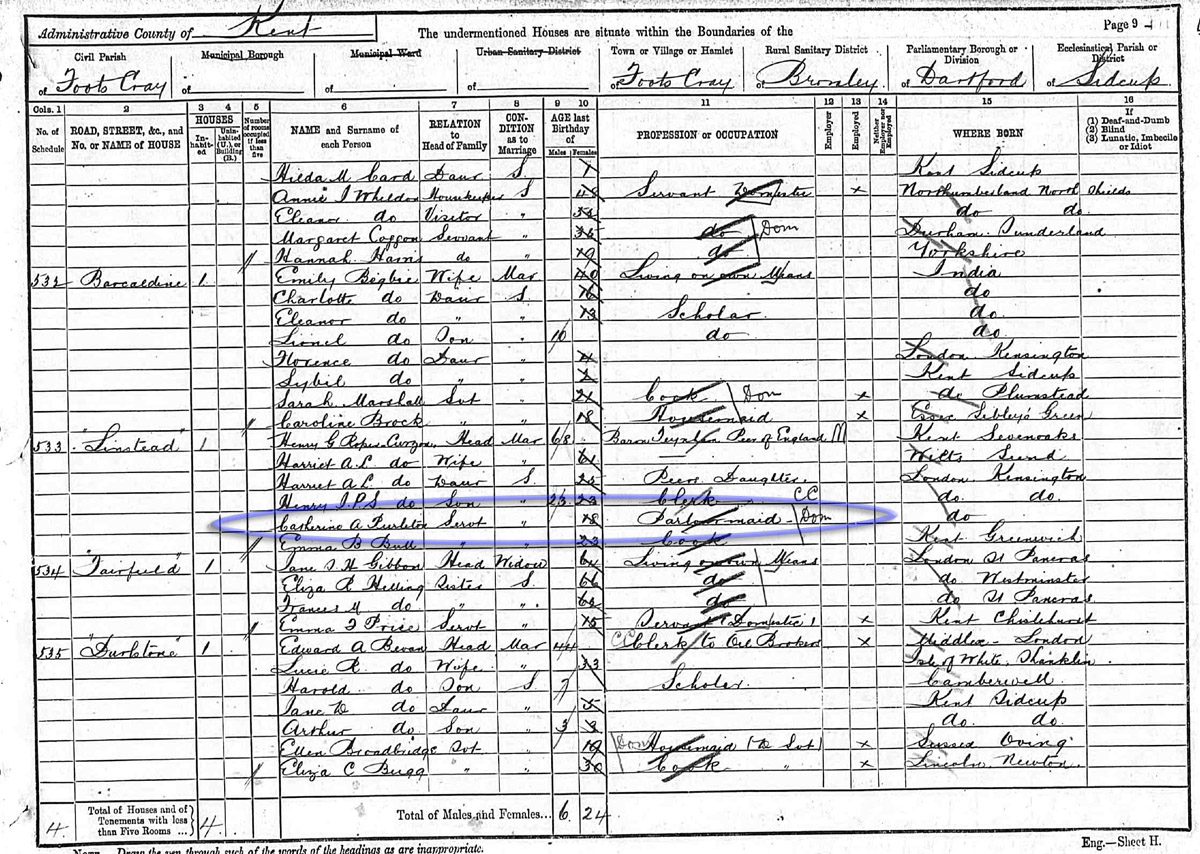

And, what of little Kate, who by now was 18 years old:

Kate's story is quite fascinating. In the 1891 census, she's of course in domestic service, but at a rather interesting address; the home of a Lord, in Kent:

This was the household of the Baron Henry George Roper-Curzon. Kate's living at 'Linstead', a modest residence where the aristocrat would reside when not sitting in the House of Lords. Partleton Tree correspondent Tony Fussey emailed us in 2008 and tells us something about the Baron:

"... when he succeeded to the peerage (and eventually became the oldest peer in the House of Lords) it seems that he was a great supporter of charities like Barnardo's, which also had a firm evangelical ethos, which he would have been comfortable with. Presumably it was through this link that Kate came to work for him."

So it seems that Barnado's probably placed Kate with a friend of the charity. Of interest to me, as a historian, is that celebrated historian Hugh Trevor-Roper (1914-2003) is a relative of Henry George Roper-Curzon.

Left: Hugh Trevor-Roper

Left: Hugh Trevor-Roper

In 1945, Trevor-Roper was ordered by MI6 to investigate the circumstances of Adolf Hitler's death and to rebut the propaganda of the Soviet government that Hitler was alive. Trevor-Roper interviewed the last people to have been present in the bunker with Hitler. The ensuing investigation resulted in Trevor-Roper's most famous book, 1947's The Last Days of Hitler. You may also remember that Hugh brought his reputation crashing about his ears when he hastily and erroneously authenticated the famous 'Hitler Diaries' for The Times in 1983.

But we seem to have strayed off-topic: we should return to the story, which, since it's about James Partleton - and he's dead - I will keep going a bit longer with his widow Emma Gould. Here she is in the 1901 census, still circulating in the same streets in Bromley-by-Bow. Church Avenue is right next to Henry Street and George Street:

Emma still has her three boys with her, though they are scarcely 'boys' any longer, since they are now 27, 30 and 33 years old.

Two of them are not destined to live much longer...

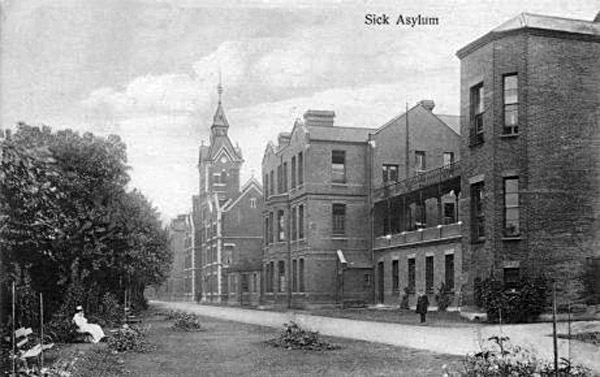

Above we see the death certificate of Charles. He died in 1907 aged 37 of pneumonia in the Sick Asylum, Bromley. This institution is right on their doorstep, as we see its location outlined in orange in the map below:

The Bromley Sick Asylum, more correctly called the Poplar and Stepney Sick Asylum, wasn't built till 1871, so the buildings don't appear in the above map, but they do appear in the 1893 Ordnance Survey Map below, which I found on the websitetworkhouses.org:

And here's what the hospital looked like, from the viewpoint of the orange arrow in the map above, in 1905, just two years before our Charles died there:

The husband of Elizabeth Stride – Jack the Ripper’s third victim – had died in here of TB in 1884, four years before his wife was murdered.

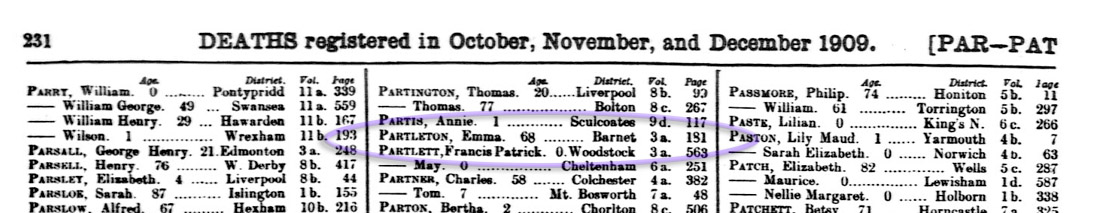

In 1908, James Partleton Jr died, aged 40:

And in 1909, having been through the grievous experience of seeing two of her sons die in two previous years, Emma Gould passed away aged 68:

The fact that Emma died in the North London suburb of Barnet suggests that she was residing in an institution.

And having seen her death, we finally get to see what Emma Gould looked like, in this c1900 photograph:

Emma, who was 60 when the photo was taken, is seated. The young woman behind her is, by all logic, either her daughter Clara who would be 25 at the time or her daughter Emma who would be 24.

If the young woman is Emma, she doesn't have long to live; she died in 1911 of pneumonia, aged 33:

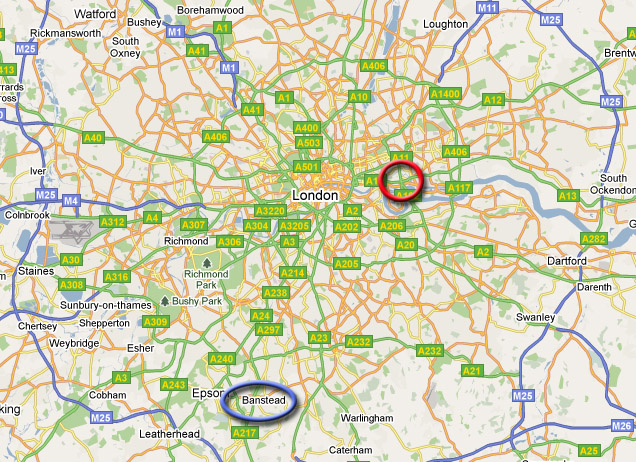

Emma jr.– who had had a hip condition which made her unable to walk as an infant - died in the London County Asylum at Banstead, which we see below. It was a mental hospital, which may or may not tell us much about her mental health.

Banstead in Surrey, circled blue, is a long way from Bromley-by-Bow in Middlesex, circled red, below:

One of the good things about creating one’s own family history website is that you get to be many things; historian; film critic; court reporter; journalist; and in this case – instant medical expert.

I say this because I have a suggestion regarding James Partleton and his children, to connect their early deaths. James, who had certainly been closely exposed to tuberculosis as a child, died of Pleurisy – a painful inflammation of the pleural cavity surrounding the lungs - which was a very common consequence of chronic damage inflicted by TB.

His son Charles (1870-1907), as we witnessed above, died of Bronchitis, aged 37. Again, a disease of the lung closely associated with TB.

His son James Jr (1867-1908) died of nephritis (kidney disease) and stricture of the urethra. ‘Surely this is unrelated’, I hear you say – but no, it turns out that this can also be caused by TB...

And in 1911, as we saw above, James’ daughter Emma died, in a lunatic asylum, of pneumonia - again lung disease - the commonest cause of which, in Victorian times was – you may have guessed – TB.

To sum up, I think James lived with, and suffered with, tuberculosis his whole life. It eventually brought him to an early grave aged 39. He passed it on to his children and it eventually killed several of them as well. The remainder probably carried it without showing any symptoms, which - you may be surprised to learn - is usually the case with TB. And I should add to that statement that I’m not a doctor and I could be completely wrong.

James Partleton lived a short, hard life. He was born into one of London's worst slums, grew up in poverty in Lambeth, saw many of his brothers and sisters die of terrible diseases, was married in Waterloo, worked hard, moved with his job to the East End of London, and died there aged just 39.

It's been a quite struggle to keep this story on track. There are always so many interesting diversions. The problem is not what to put in, but what to take out. If you'd like to read more about James' childhood in and around Drury Lane, a big chunk of history which I removed for the sake of the flow of the story, click here.

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'In Their Shoes' Page.