James Partleton (1837-1876)

Addendum

You should have been directed to this addendum from the story of James Partleton. To read James' story, click here.

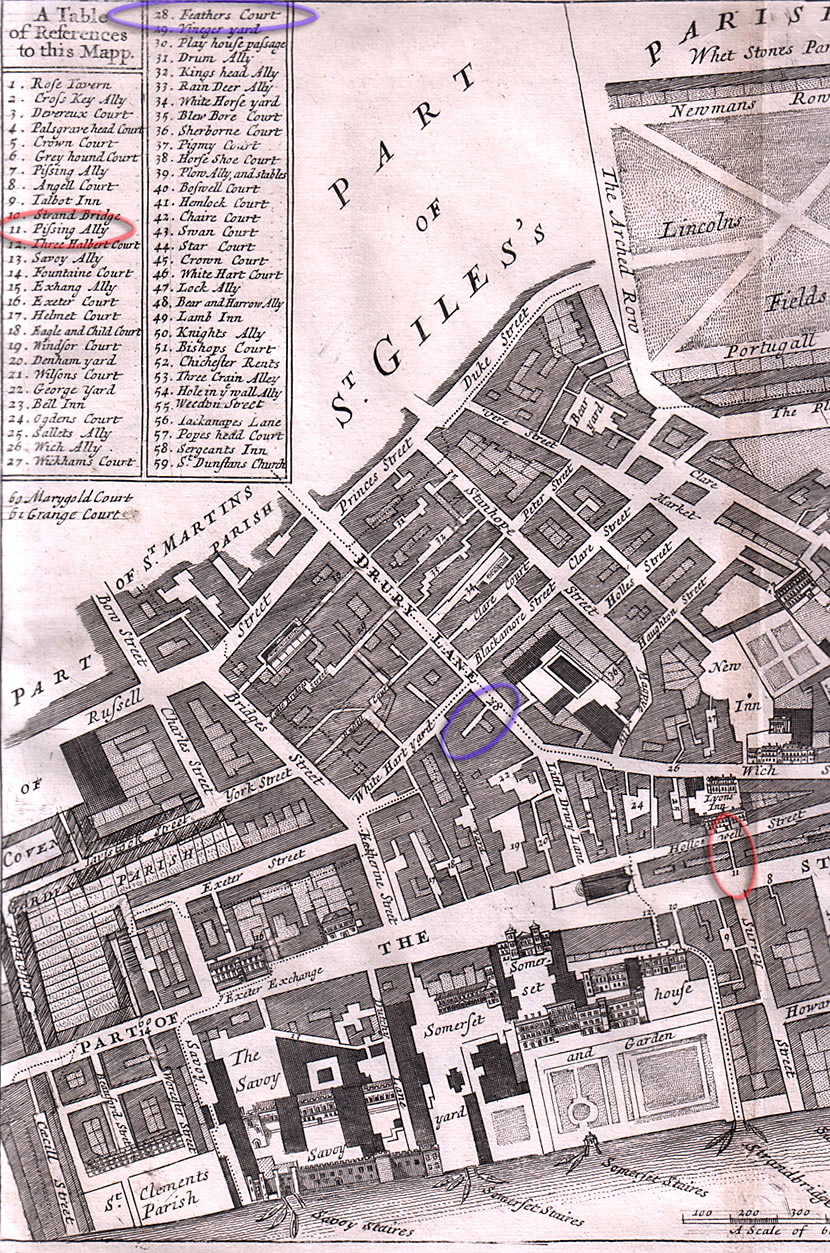

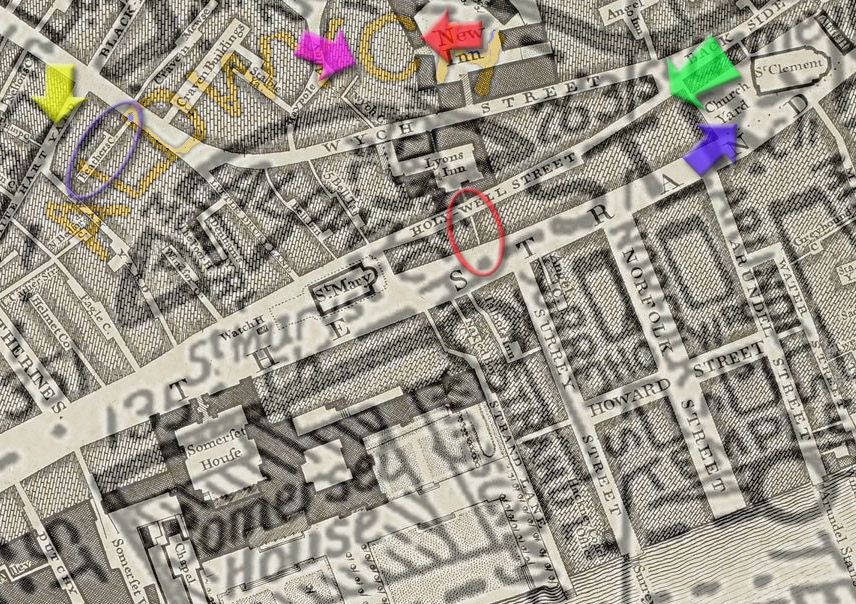

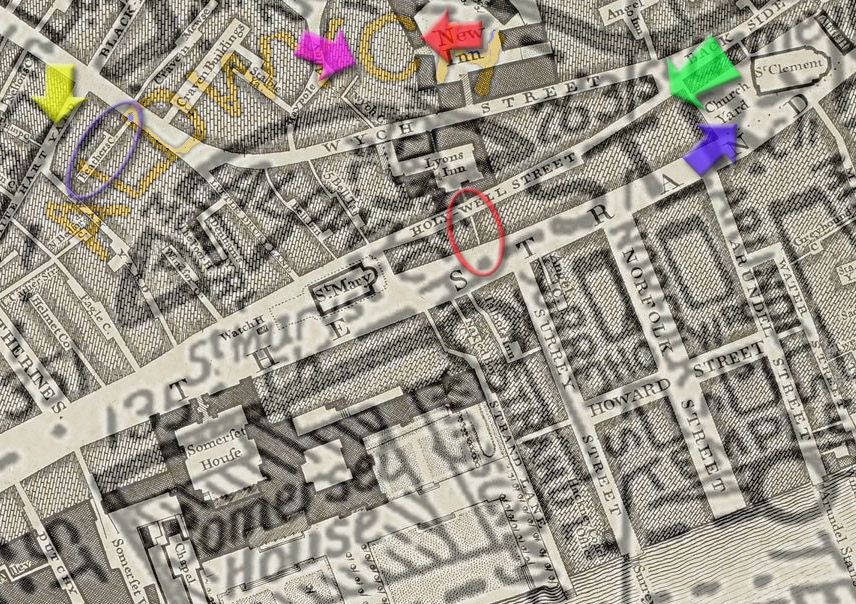

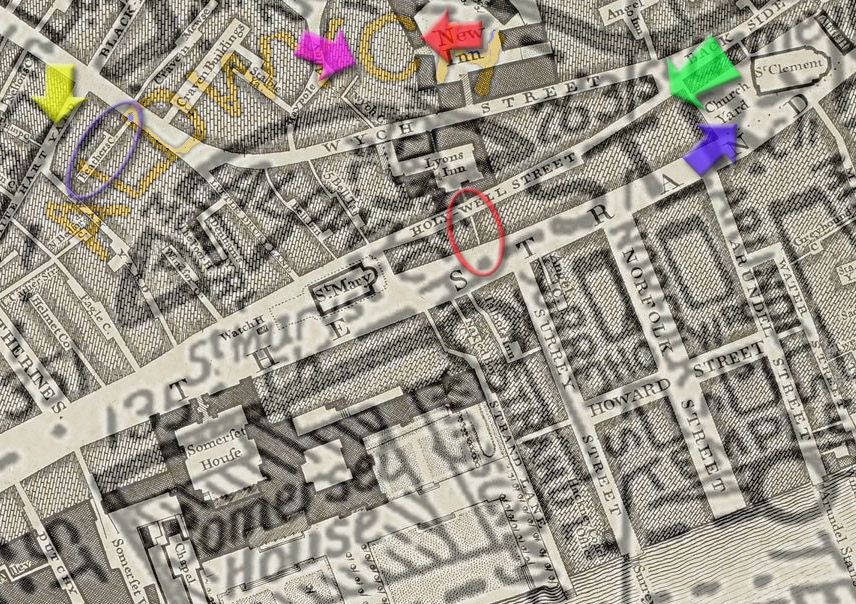

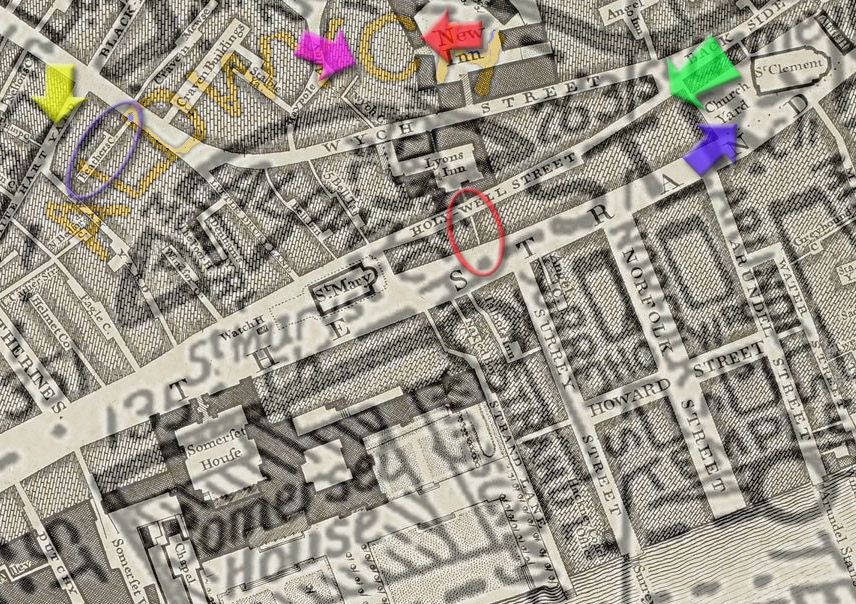

We're going back to James' place of birth, where he lived till he was nine years old; Drury Lane, in the blue circle:

From age 2 to 9 years old, James lived at Feathers Court, circled blue in the map below:

As a child of London's poor, it's unlikely that our Charles actually had shoes. He would have been a typical barefoot street urchin.

So let's step into his bare feet - if that's possible - and have a run around his childhood stamping-ground with him. He can be our guide - he would know every square inch of these streets.

Our first picture is from the viewpoint of the yellow arrow - along Wych Street, which we see below by an anonymous artist. It's a new picture to this website, the spire of St Clement Danes church giving the picture some distance:

This was engraved some years after James had left the area, but of course, the streetscape was unchanged.

Also from the exact same viewpoint of the yellow arrow, we can compare an earlier image (1825), below. The artist stood at the entrance to the New Inn, one of London's ancient Inns of Chancery, legal establishments where solicitors carried out their business, as evidenced by the lawyer at the bottom left of the picture. The houses below can be matched one-to-one with the later engraving which we saw above:

This is a rather 'chocolate-box-style' painting: the road has been widened by the artist, everyone is dressed in their finery, and the the stagecoach is apparently thundering down the road at some speed, which if you look at the previous engraving, would have quite impossible in narrow Wych Street.

Indeed, it's altogether a rather unusual-looking image... is it a tapestry? Can you figure out what the picture is printed on?

In fact what we were looking at is a book, edge-on, with the image printed on the edges of the leaves. Now that we know that, it becomes obvious. The book is The Rambler, by Samuel Johnson, printed in 1825, owned by the Boston Public Library in the USA.

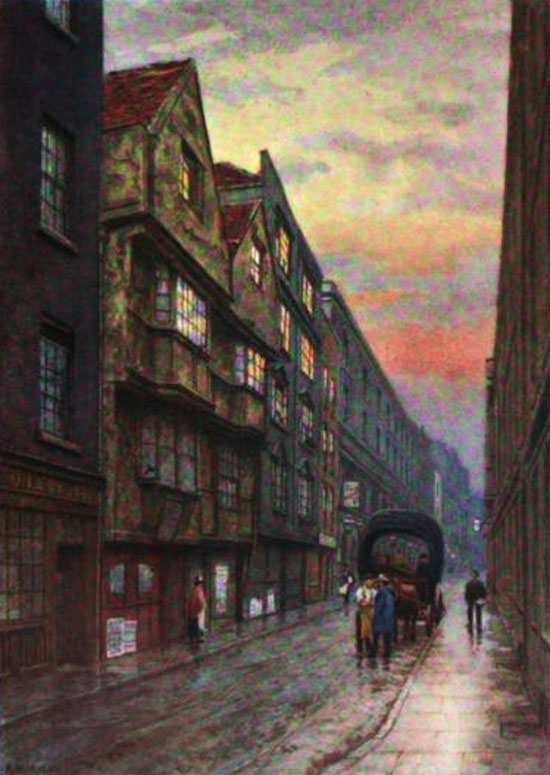

In our last image of Wych Street, an anonymous Victorian painter - I can't discern the signature - captured the following scene, from the viewpoint of the dark blue arrow, looking west towards the pretty sunset, at dusk after a rainy day, c1900. Wych Street has a melancholy air; the whole street was soon to be flattened, during the first decade of the 20th century, as part of a massive slum clearance and redevelopment scheme:

Next, we are going to make a long journey into the tale of Holywell Street, at the point of the pale green in the map.

You may feel that we lose our James somewhat amongst all these images, before and after he was born.

But - whatever - let's start our detailed odyssey through his childhood haunts.

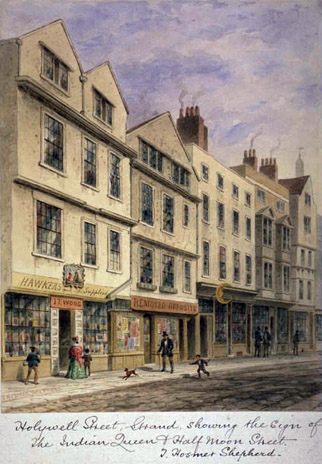

In the painting below, by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd, we stand with our back to St Clement Danes church, from the viewpoint of the turquoise arrow, and look westwards towards the junction of Holywell Street, branching left, and Wych Street, branching right.

The view we see above, which was executed c 1851 is exactly how James would have seen it as he lived in this area from 1837 to 1846.

Below we can contrast Thomas Shepherd's image of 1851 with the one on the right, by John Crowther, fully 30 years later, in 1881:

iiiiiiii

iiiiiiii

Holywell Street was famous, notorious even, for two things: second-hand books and second-hand clothes, and we see one example in the 1851 painting on the left above - Joseph Dashwood's second-hand clothes shop at No 1 Holywell Street.

The 1881 painting shows the building on the right has been converted into a pub, The Rising Sun, and in the photograph below - which was taken in the early 1900s - we can barely see the Jacobean building behind the gaudy advertising which includes a newfangled electric sign for Dewar's Whisky:

Also evident in the photo above are numerous Edwardian gents perusing the contents of the bookshops along Holywell Street. Some of the customers may have been a little furtive, as many of the bookshops were notorious for selling pornography, about which we learn more later.

60 years earlier, James Partleton's mum, Mary Ann Garrad (1807-1873) had a brood of six little kids when the family were living at Feathers Court. She had to clothe them all, and with very little money available, it seems to me quite certain that at some point she would have browsed and shopped along Holywell Street at establishments like Dashwood's for used clothes for her family:

So, now we know where we are, let's examine some views of Holywell Street in chronological order:

Here it is from the pale blue arrow. We are looking eastwards and it's the Church of St Clement Danes peeking out in the background. The year is 1816; the artist; Robert Schnebbelie:

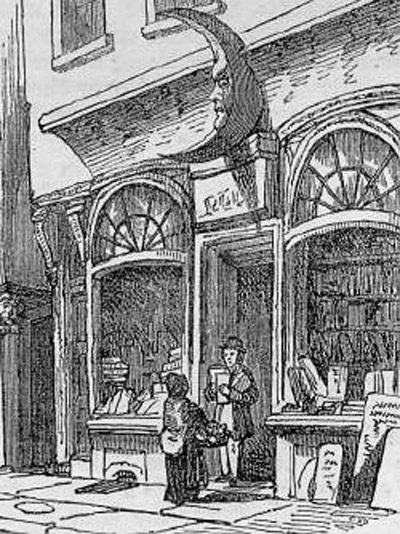

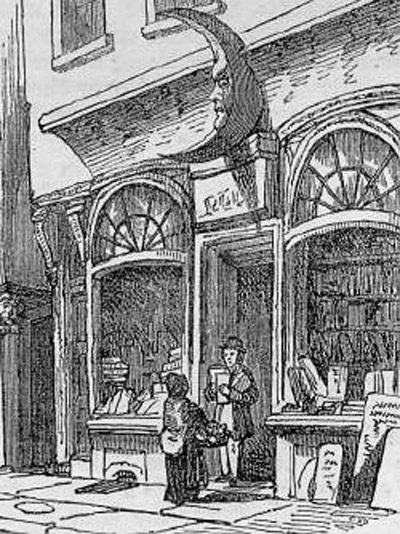

See that half-moon shop sign? Keep your eye on it 'cause our James was familiar with it, and you'll see it in every picture from 1816 to 1900.

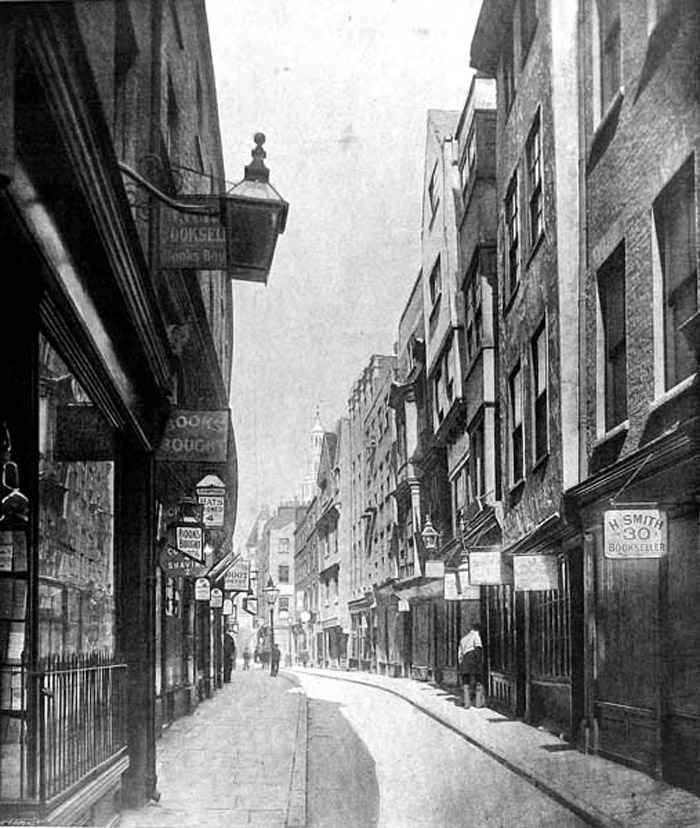

Roughly forty years after the previous picture, close to the time when young James Partleton was knocking around, we see the same shops in the 1850s, from the opposite direction, the pale green arrow. This time - because we are looking westwards - it's the church of St Mary-le-Strand in the background:

In fact we can see two near-identical views of this spot as the Victorian artists jostled elbows, figuratively speaking, to depict these charming old houses:

iiiiii

iiiiii

The painting on the left above is by a Victorian friend to this website, Thomas Hosmer Shepherd (1793-1864), whose depictions of Victorian Streets will surely endure the ages. The one on the right is by W Richardson, the buildings apparently leaning over to peer at the buzz of human activity in the street.

Again we clearly see the good-old half-moon sign in the painting below, which is held in the British Museum; the year, 1862; the artist; John Wykeham Archer:

And the one below is by another Victorian hero, John Crowther, who painted almost exactly the same scene 20 years later, in 1882.

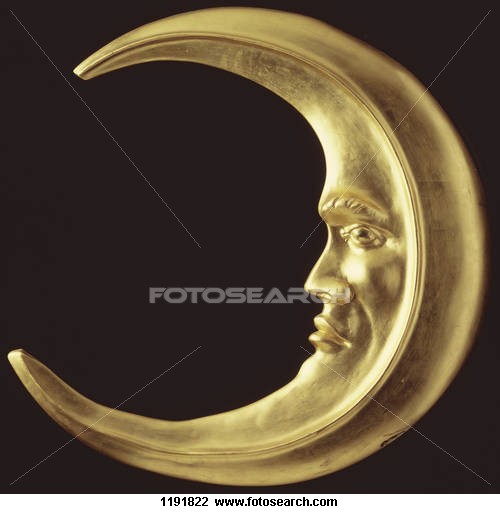

And John Crowther also took the trouble to depict the beautiful half-moon sign close-up; we see its wonderful stern countenance:

The sign was well-known; we can turn to a cute Victorian history book for some more information:

Just look at that angry moon - James Partleton, or any child, running down this street in the 1840s would certainly be interested in it!

Clearly the Victorians were already regarding this sign as a rare relic of a disappearing past.

Before the 19th century, shops, especially mercers, often had signs, and these often bore no relationship to what they sold. Just like the pub signs with which we are all familiar. The sign was simply a powerful mnemonic by which people would remember the shop.

The sign can still be seen - 80 years after our first painting - in 1896 in an illustration from the book Reliques of Old London:

Finally, we get to see an exquisite photograph of 1901, looking eastward down Holywell Street, with the demolition of the street looming, and we observe the bookshops close-up:

This time, we look carefully again at the right-hand-side of the street and... it's gone! The half-moon sign has been removed! Holywell Street was doomed to destruction quite soon after this photograph, and I reckon, hopefully, someone has probably taken down the man in the moon to preserve him...

Let's dig out Thomas Hosmer Shepherd's watercolour of 1853 again. He graciously uses the name Half-Moon Street in the title of his painting;

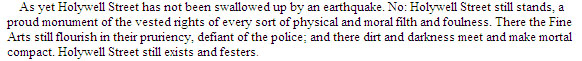

but this was really Half-Moon Alley, aka Half-Moon Passage, a tiny alleyway linking Holywell Street to The Strand, circled in red below:

We see the alley clearly in this 1847 watercolour by John Wykeham Archer, squeezed between 36 and 37 Holywell Street. It barely looks passable:

By examination of this watercolour, we can discern that the Half-Moon was obviously a junk shop in 1847, a year after our James lived around the corner. Also noteworthy in the above picture is the lion's head which adorned the top-left corner of Half-Moon Alley.

The lion's head is there because this alleyway leads from The Strand to Lyon's Inn on the north side of Holywell Street.

"What's Lyon's Inn?", I hear you say. Well, Lyon's Inn was a legal institution, another of the Inns of Chancery. Now, I know, gentle readers, that information doesn't move us very far forward, so let's try a little harder. A chancery court is a court that is authorized to apply principles of equity, as opposed to law... Mmm, this ain't helping. But if we add the knowledge that the notion of equity allows the court not to be bound absolutely and inflexibly to the letter of the law, but to be able to use some discretion to apply a measure of common sense and natural justice to its decisions, I think we have grasped the basic premise of the Inns of Chancery.

In his 1907 book Origin and History of English Inns of Chancery, author H Spenden Steel says that Lyon's Inn became a disreputable institution that 'perished of public contempt long before it came to the hammer and the pick'. It was dissolved in 1863. James Partleton would be familiar with the sight of lawyers in their robes wandering through Wych Street and Holywell Street, but he may not have been aware that Lyon's Inn was inhabited only by the lowest lawyers and those struck off the rolls.

Below we see the internal courtyard of Lyon's Inn, with the aforementioned hammers and picks in evidence, under demolition in 1862. The archway in the middle distance leads either to Wych Street or Holywell Street:

So that was the end of Lyon's Inn. It was replaced by the new Globe Theatre. But the lion on the wall at the entrance to Half-Moon Passage lived on...

In 1880, John Crowther decided to give us a superb close-up view; [courtesy of the City of London Archives, whose watermark is splatted over our lion's face]. You can also see the big cat in the c1840 engraving on the right:

iiiii

iiiii

But when John Crowther returned in 1882, the entrance to the alleyway has been smartened-up with an arch, or so it appears;

I wondered about the fate of the lion's head; and after some persistence the answer emerged in the book London Signs and Inscriptions, written in 1893 by Philip Norman, who repeats some of the story published in 1883, but we also learn more about the good old Half-Moon:

The author blushingly refers to Half-Moon Passage as previously having an 'unsavoury name' but coyly does not reveal what it was. Anyhoo, the stone lion's head ended up in the Guildhall Museum, which became part of the Museum of London in 1976, and it must still be there now in their collections. I shall surely go to look it up one day.

That still leaves the mystery of the missing-alleyway-name, and, since Mr Norman cites his source as Strype, we can go to the original text, from the book Strype's Survey of London, originally published in 1720:

This later edition of the book is also a little coy about printing such a vulgar name, but I have no such scruples. If you can't fill in the blanks, I can reveal Half-Moon Passage was originally called Pissing Alley, named plainly in John Stow's 1720 map below, circled in red, and I think the description is surely a literal description of what it was used for, as alleyways often are, rather than a mark of contempt as speculated by John Strype.

In our James' time, the Victorians called Holywell Street Booksellers Row, because of the preponderance of... well, bookshops of course. The Strand becomes Fleet Street a few yards east of St Clements Church. Fleet Street, as our British readers will know, was famous as the home of British publishers and newspapers for nearly 500 years till the late 20th century. Publishing was also big business on The Strand.

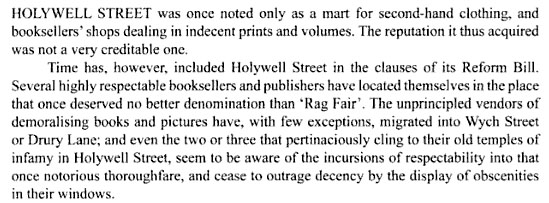

We know our James was not a big reader - he couldn't even sign his name - but in this case it possibly was for the best that he was illiterate. Many bookshops on Holywell Street were notorious for selling pornography, as we learn in The Mysteries of London, by George Reynolds, written in 1844 whilst 7-year-old James was living at Feathers Court just around the corner:

The writer's optimism was misplaced. The x-rated bookshops did not just go away, and continued to be lambasted in the press for the whole of the 19th century, as typically reported in The Times of 23 July 1857:

'It is a fact that in certain parts of London, and notably in Holywell Street... prints, song-books and other publications of the most disgusting character are exposed to public view'

And the satirical magazine Punch on 19 January 1856 had hoped that Holywell Street might be smitten by God with an earthquake:

Three months later; 08 April 1856, and Punch reports with some satisfaction that some of the dirty-book dealers had been arrested, and suggests life-imprisonment in a lunatic asylum as a suitable punishment:

What constituted pornography in Victorian times? Perhaps we might find it all a bit tame? But a bit of internet research yielded the fact that the predominant magazines purchased on Holywell Street were The Boudoir and The Cremorne. The content of these magazines pandered to some pretty bad taste tending towards sadism, and were graphically illustrated. And a page of dirty limericks which I found was about as coarse and vulgar and unfunny as you can imagine; not for repeating in a family-tree website.

Let's move on.

As you can see in the map below, the two churches which stand in the middle of the road in The Strand - St Clement Danes and St Mary-le-Strand - cause a narrowing of the street and considerable traffic constriction. As a consequence, Holywell Street and Wych Street lived for a long time - at least 60 years - under the threat of their demolition for road-widening schemes.

The irresistible forces of change, and the city planners, eventually got their way. Holywell Street fell to the wrecking-ball - though James never witnessed it; he was long dead.

To finish off the subject of shop signs, there was another in Holywell Street which might not be quite so appealing to a child, but which James would have passed by many times:

xxxxx

xxxxx

In Thomas Hosmer Shepherd's 1853 painting above, he references the sign of the Indian Queen, a shop two doors up from the Half-Moon, and we get a tantalising glimpse of the aforementioned queen on the shop sign in the painting, seen larger in the inset above right. The Indian Queen was quite a common name, both for pubs and shops [as was the Half-Moon]. In this case the shop on Holywell Street had certainly been a mercer in 1783.

I can't let that just drift by. What exactly is a mercer? I've heard that word, but it has fallen out of use, and I never knew its meaning, beyond being a merchant of some kind. It turns out, as many of our gentle readers probably already knew, that a mercer sells textiles.

We can't see the Indian Queen sign in the 1816 painting - it's obscured by a carriage:

But we can use this picture to illustrate our next story; a theft which took place at the Indian Queen on 25 October 1817, as noted in the records of the Old Bailey Courthouse, courtesy of the website Old Bailey Online:

We shall need to dip into the dictionary again. A tippet is a cape with long ends. The story doesn't tell us what was sold in the shop; the stolen articles seem to be personal possessions of the owner.

Finally, I'll put the three paintings side by side, 1816 (left), 1853 (centre) and 1882 (right), because they are interesting to compare. Nothing changed in our James' lifetime!

iiiiiii

iiiiiii iiiiiii

iiiiiii

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Sword of Damocles which had been hanging over Holywell Street and Wych Street finally dropped. The shopkeepers were kicked out in 1901, and the London County Council commenced demolition of the whole area at the south end of Drury Lane. It was a gigantic piece of work which took decades to complete.

Below we see the sad remains of Wych Street and roads to its north on 26 May 1903 in a photograph held by English Heritage:

We can see the steeple of St Mary-le-Strand in the background. The photo is taken from the yellow arrow in the map below:

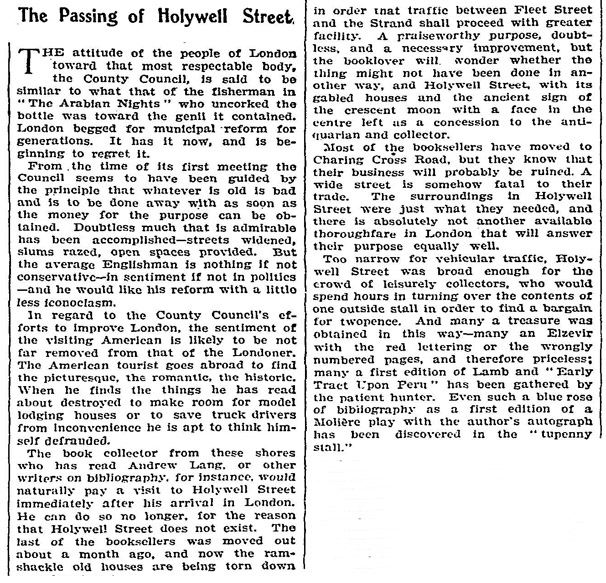

Surprisingly, the best source I could find lamenting the loss of the old Elizabethan buildings in Wych Street and Holywell Street was in the New York Times of 01 September 1901:

Lastly, we see an aerial view of the redevelopment in progress, in the 1910s. Bush House - the main feature of the new Aldwych - hasn't been started yet; its site is occupied by workmen's huts. There were complaints from the public about the slow pace of the work:

In fact progress on the Aldwych was incredibly slow. The next photograph is 1921. Bush House has only just been started; scaffolding is up. The first part of it was eventually opened in 1925, and having cost $10million, it was described in 1929 as 'the most expensive building in the world'.

When you walk past Bush House today - as I do every day in 2013 as I make my way from Waterloo station to Holborn - its appearance is so ordinary that's it's hard to understand why it took so long to build or cost so much. From 1941 to 2012 Bush House was home to the BBC World Service radio station.

Built and funded by American business magnate Irving Bush, the BBC have never owned the building; as is often the case with buildings, its owners over the years have been weird and wonderful; the Church of Wales; the Post Office; and presently [2013] a Japanese business conglomerate. That's a little ironic since it was created by Irving Bush to be a majestic symbol of Anglo-American trade.

To show just how vast the Aldwych/Kingsway scheme was, below I have overlaid a 1930s map on top of the 1740 map, below. You'll have to work with me here - look carefully and you'll see both maps! Compare the inset for help.

The aerial photograph is from the green arrow looking at St Mary-le-Strand. See if you can figure out where Wych Street and Holywell Street used to be!

iii

iii

Note also, top left of the map, Feathers Court, circled blue, being swallowed up under the new road surface of the Aldwych.

The Aldwych today is a rather uninteresting sterile piece of centrally-planned workmanship.

So - I hear you ask - "Does nothing remain of old Holywell street?"... aside from the stone lion...

well...

What you see above turned up as a pleasant surprise in a google search. Clearly it is our half-moon sign; the dating, 'mid 18th century' is bang-on - it's even tagged - not for nothing - with Holywell Street, circled in red.

Unfortunately fotosearch.com do not cite the location of this artefact, though it seems highly likely that it must be sitting in a museum somewhere [maybe the Museum of London like the lion], as it has been catalogued and carefully photographed. We can get a closer look:

One thing's for sure in all this; our James, as a young boy in the 1840s, would certainly have gazed up at that half-moon sign with its apparently frowning moon-face!

James Partleton's home, Feathers Court, circled blue, as mentioned earlier, was also demolished at this time, but it was not especially old and it certainly wasn't charming like Holywell Street. It was a squalid overcrowded slum. Here's a photo of Angel Court, just 30 yards away as the crow flies, seen from the red arrow, which will give us a pretty good idea what we should envision. This is what young James' home looked like from the outside:

If you're ever in the neighbourhood of the southern end of Drury Lane, there's no use looking for any fragments which might remain from James' time. It's all been replaced. All the buildings are Edwardian or later.

When Feathers Court was knocked down, here's what replaced it on the exactly the same spot - the Aldwych Theatre, which I know still looks exactly the same [2013], because I walk right past it every day on my way to work at Holborn. The horse and cart in the picture are directly on the location of the former Feathers Court, James Parleton's childhood home.:

The Aldwych Theatre was completed in 1905.

Its facade was blown out and windows broken by a V-1 flying bomb on 30 June 1944:

The above picture was taken from the viewpoint of the purple arrow in the overlay below:

iii

iii

An uncredited photographer standing in Fleet Street, with St Dunstan's church in the foreground, took the following extraordinary photograph of the event a few seconds after it occurred; some Londoners are scurrying into the street to rubberneck the spectacle occurring a mile or so away; others hop off a bus and, - since there's absolutely nothing they can do about it - turn their backs to the mayhem, as I would do. They've seen it all before.

iii

iii

The Aldwych Theatre - the location of the former Feathers Court - can be seen in the photograph below, picked out by the yellow arrow. The photographer stood from the viewpoint of the red arrow in the map above:

iiiii

iiiii

The road turning to the right in the two photos above - 1944 and 2009 - is Houghton Street, where James was born, circled in red below, though the house had been demolished long before Hitler tried to blow it up - to make way for part of the London School of Economics.

Here's Houghton Street, looking south towards the Aldwych:

Left; 2009--- --Right; 1928

Left; 2009--- --Right; 1928

In the 2007 photograph, left, all the buildings are of 20th century, the LSE. In the 1928 photograph on the right, we see the same arch in the distance, but we also see Houghton Street as it looked when James was born. What we see is the row of houses opposite James' birthplace.

In a separate incident, the church of St Clement Danes did not escape the blitz, as, in another extraordinary photograph, we see it ablaze from the Strand in 1941:

The fact that The Strand is right next to Fleet Street - home for decades to national newspapers and their photographers - may account for some of these great pictures, though they are uncredited. The photo was taken from the blue arrow in the overlay map below. The tower survived the fire, and the church was restored after WW2.

iii

iii

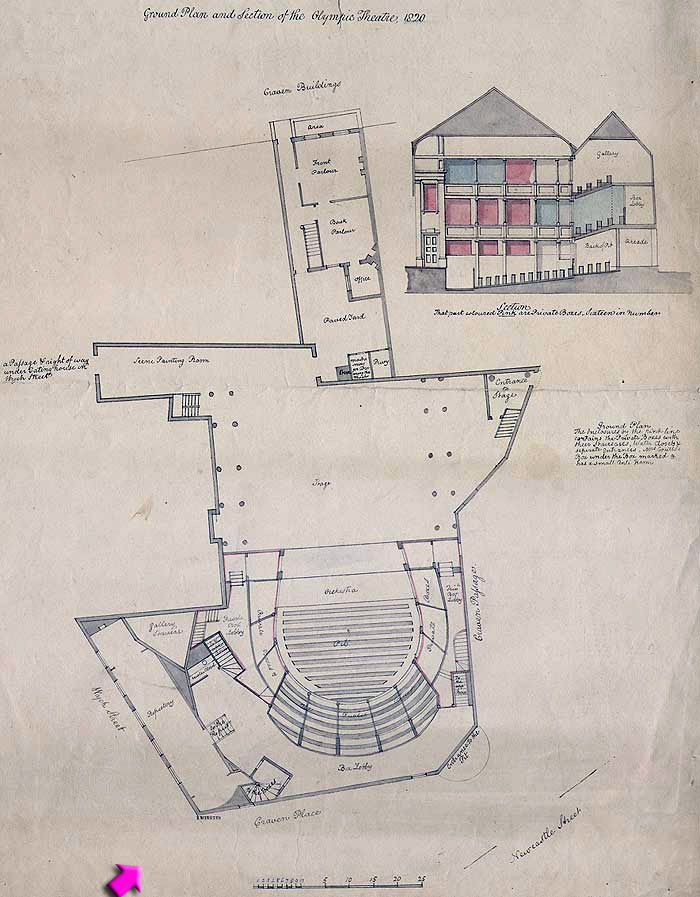

Let's get back to our James. Rewind 100 years from the 1940s to the 1840s. Right on his doorstep, on the short walk between Houghton Street and Feathers Court, was the Olympic Theatre, outlined in purple in the map, with its entrance on Wych Street:

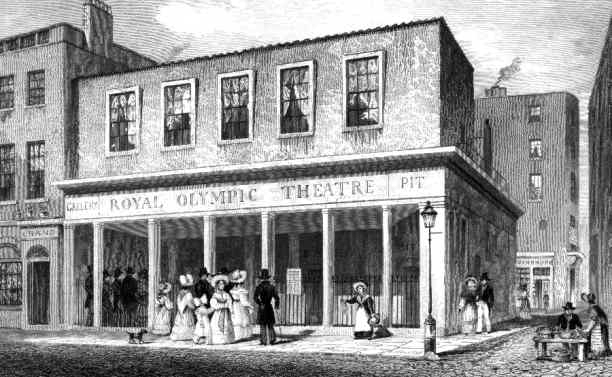

In the engraving below, we can see its frontage exactly as James would have seen it, from the viewpoint of the purple arrow:

The small Olympic Theatre was built in 1820, replacing an earlier structure built by entrepreneur Philip Astley. While searching on the internet, I found the 1820 architect's plan. The above viewpoint of the frontage from the purple arrow, on Wych Street, is indicated on the plan:

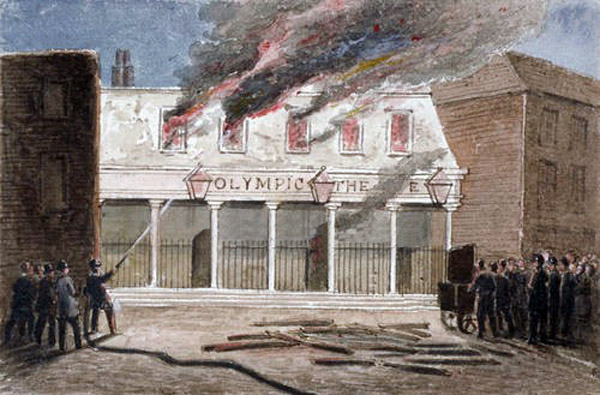

It must have been the naked-flame lighting, or something, but theatres in those days used to combust like dry gunpowder. The Olympic Theatre burned down in 1849, 3 years after our James had left the neighbourhood.

It was replaced within the year by a new theatre built to a very similar design, which we see below. I suspect they might have just blown the dust off the original architect's plans:

I found the engraving below described as the interior of the 2nd Olympic Theatre. But I'm not so sure - from the fashions I think it might be the first one:

In a short-sighted manoevre, the Olympic was rebuilt yet again, in 1890, even though it was common knowledge that whole neighbourhood might soon be razed. Below we see it in its 3rd guise - it only survived about 13 years before it came down again with the Aldwych redevelopment:

As for James Partleton. Even though his family were dirt-poor, his dad had been a stage performer in his youth, and it would be highly surprising if they didn't occasionally visit the theatres which bristled in every available spot in this part of London, as they still do today.

As a postscript to this tale, I had a look for the Holywell Street half-moon... and found it! It's definitely in the Museum of London:

Perhaps I'll tell them that it's not from a pub... and that they've spelled Holywell Street wrong!

In December 2011, Partleton Tree correspondent Paul Little wrote to say that the half-moon was on display in the museum for an exhibition of Victorian London:

But sadly, by the time I got to visit the museum in October 2012, the moon had been returned to storage. Doh.

And that's that for our diversion into the childhood of James Partleton (1837-1876). If you think it ended a little abruptly, well, it was only an addendum!

To read the whole of James' story, click here.

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'In Their Shoes' Page.