Charles 'Wag' Partleton (1868 - bef.1921)

Part 2

This page is a continuation of the story of Charles 'Wag' Partleton. Click here to return to Part 1.

To summarise, Charles Partleton, nicknamed 'Wag', was born 1868 in Lambeth. He grew up in circumstances where money was tight, and in his teens joined the British army where he was posted to India for eight years. Back in civilian life in London in 1896, Charles married widow Susan Pirie in Camberwell, and he has taken up employment working as a labourer in the building trade.

After the wedding, the married couple moved back to the centre of Lambeth. Their address is given as 12 Vauxhall Street - see the dark green arrow in the map:

A tiny chunk of Victorian Vauxhall Street survives today, which would be entirely familiar to Wag. From the point of view of the dark green arrow we can see a gasholder at the end of Vauxhall Street below - Waggy is back in the neighbourhood of his beloved gasworks:

Just when you thought we had left the subject of gasworks for ever, they have come right back into the frame. The gasholder we see in the picture above is not the London Gasworks which we saw earlier on this web page. This is the Phoenix Gasworks. And, if the world has a Most Famous Gasworks, then this is it!

The aerial photograph above, taken in 1938 - from the viewpoint of the large brown arrow in the map - shows Kennington Oval, one of the most famous cricket grounds in the world. Cricket lovers will know that the north end of the ground is affectionately referred to by the commentators as the Gasworks End and that images of the good old gasholder feature hugely every time there is TV coverage of major cricket internationals at the Oval. On 20 August this year (2009) England will face Australia for the grand finale of the five matches for The Ashes, cricket's most prized trophy, and one of the greatest rivalries in any sport. The venue will be the Oval.

My dad, who was Ukrainian, found cricket incomprehensible. A game which lasts for five full days, and ends - more often than not - in a draw. "Chonk, Chonk" he called it, in imitation of the sound of the bat on ball. But the funny thing is that in his retirement, with time on his hands at home, he eventually came round to enjoy watching the leisurely, fascinating progress of a game of cricket on TV; glorious summer days, the battle of bowler vs batsman, and indeed the sound of willow on leather.

So, we are going to have a diversion into the history of the Oval, because it's a major feature of Lambeth, and one which almost certainly featured significantly in Waggy's life.

In the 1799 map above, we see the Oval at the bottom right, surrounded by fields.

A closer look reveals curious markings inside the oval:

The reason for the striped appearance of the Oval is that it contains orderly plantings criss-crossed with paths. It's a market garden.

In the picture below, of 1815, we see a gardener at work in the Oval, and - if my eyes don't deceive me - a couple of pigs in the street outside the garden:

In 1845, the Surrey Cricket Club leased the Oval from its owners, the Otter family, and converted it to a cricket ground with 10,000 turfs brought from Tooting Common.

Soon afterwards, in 1848, our much-featured Phoenix Gas Works was built on the north side of the the ground:

In the engraving below, of 1849, and a game in progress watched by a smattering of spectators, we are inside the oval looking towards the south-east from the khaki arrow, with the clubhouse inside the ground at the left, and St Mark's Church in the background behind it:

And here's the Surrey cricket team of 1862:

In the photograph below, taken inside the Oval in c1860, from the point of view of the sky blue arrow, we are looking north, where we see the Phoenix Gas Works on the right. There are no covered stands in the photo, just fences around the boundary, indeed no covering for spectators was built until the 1890s:

I'm not sure who the gentlemen are, playing in their black suits and black hats in the heat of the summer, but there were some quite odd games played at the Oval, like this one in 1862 between two teams of wounded Army Veterans - One Arm vs One Leg:

The cricket County Championship began in 1864, with Surrey playing their home games at the Oval.

Our Charley was born in 1868, and the Oval is moving into an era when the it is going to host to massive events of world significance. The first of these was the first-ever international football match, between England and Scotland, held in front of a large crowd on 05 March 1870, when Charley was just two. The game ended 1-1. The England national team would continue to play football at the Oval until 1889.

Below we see a football game at the Oval, from the Illustrated London News of 1876. It's clear from the badges that it's England vs Scotland. The picture is titled Football at the Oval, but in 1876 the game - which was annual - was in Glasgow, so it's probably the 1875 game, which ended in a 2-2 draw. Pill-box hats were no obstacle to heading the ball, it seems.

The next huge event was the hosting of the first-ever football F.A. Cup final - held at the Oval on 16 March 1872, when Charley was four. This seems very apt as I am writing this part of the narrative on Cup-Final day in 2009. The Wanderers beat the Royal Engineers 1-0. The Oval would host all Cup Finals, with one exception, until 1892, on which occasion the attendance was 25,000.

All this football seems a bit much for what is - after all - a cricket ground. In 1878, when Waggy was 10, the Australian cricket team came to the Oval amidst much publicity, and the capacity of the ground was severely tested by 20,000 spectators jostling to cram in despite admittance being raised to 1 shilling.

The next Australian visitors were in Lambeth on 06 September 1880; the excitement at the Oval captured below in an 1880 newspaper:

Then on 29 August 1882, with Wag now 14, the first ever official Test Match was held at the Oval, seen below.

Australia won, a game of great drama, by 7 runs, and on 02 September 1882 this mock obituary appeared in The Sporting Times:

Thus The Ashes were born, reputedly the ashes of a bail held in the urn on the right.

What impact were all these spectacular events having on Waggy? Cup Finals and early England Internationals being held while he was growing up just a hundred yards from the ground?

One thing for certain is that, in later years, all his sons and grandsons had football in their blood - 'football mad' wouldn't be putting it too strongly - so it seems to me to be quite unlikely that he would have just ignored all of these great sporting events which were being hosted on his very doorstep when he was a teenager. Maybe he even attended one or two of those early Cup Finals or Test Matches. Below, the ground is creaking at the seams for a match in the early 20th century:

In WW2, the Oval was requisitioned by the government and converted to a temporary holding camp for Prisoners of War. Some fairly rustic-looking barbed wire fence-posts in evidence in the photo below. Hey - there was a war on!:

As things turned out, the Oval was never needed for this purpose, but it was used to house searchlights to pick out the Luftwaffe.

The next picture is a brilliant one: the year is 1953, but some of the the streets of Lambeth still look exactly as they did to Wag in the 1870s. Schoolboys play cricket, at some threat to the windows the the street:

This location must surely be Montfort Place, from the point of view of the purple arrow in the map below:

"Where's Waggy in 1953?" I hear you say... of course, he's long dead, but don't worry, we're nearly finished with the Oval.

Here's some spectators getting a free view to a match in August 1953 with our good old gasometer in the background. Their perch looks a little uncomfortable.

Gasometer fact: did you know that the huge tubular section in the middle rises up and down to maintain the gas pressure? You'll see it if you compare the many pictures on this page.

In 1957 the groundsman at the Oval found himself continually mobbed by angry pigeons as he tried to prepare the pitch. His solution - scarecrows:

In 1970 the barbed wire made an unexpected comeback at the Oval as cricket was threatened by anti-apartheid protesters who were angry about England's refusal to ban cricket with the white-only South African cricket team and England's cowardly dropping of its black player Basil D'Oliveira for a tour of South Africa:

In the next picture, some spectators are still getting a free view, 50 years after that first lot, this time from from the roof of a vacant pub, in the 2000s. You've got to be pretty keen to risk death just to watch a cricket match:

In 2004, the Oval received a much-needed improvement with a new stand.

Still the old Phoenix Gasworks stands sentry over the ground:

Yes, I know we have left Waggy far, far behind. It's high time we caught up with him again, so let's rewind rapidly to Lambeth on 18 July 1898 when my maternal granddad Frederick was born:

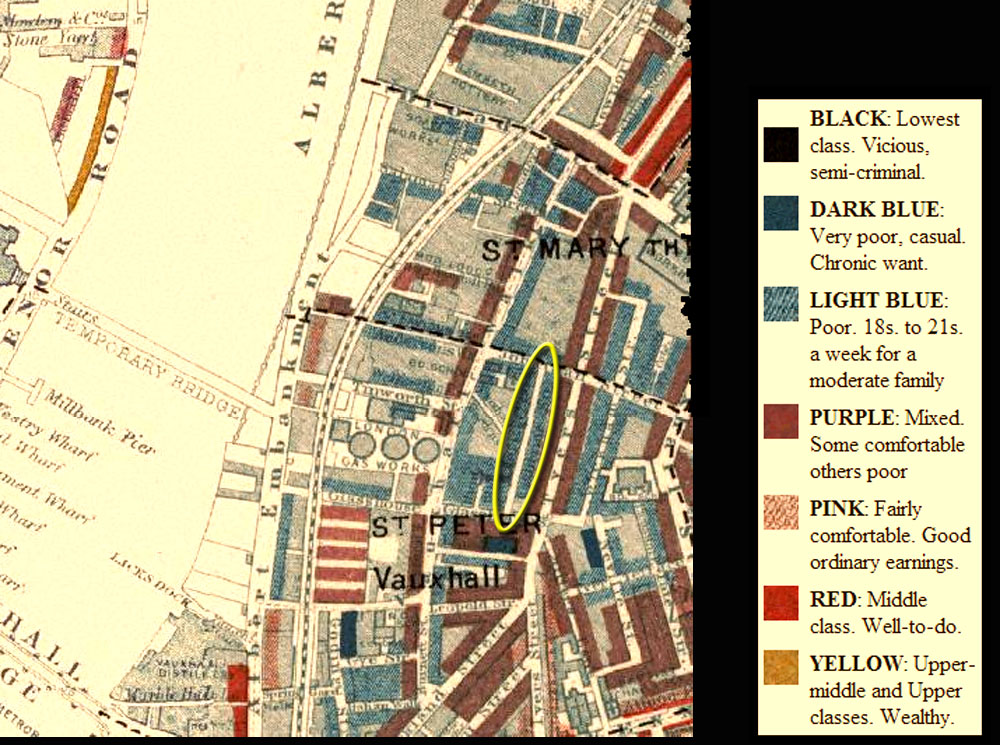

Their address in 1898 is Neville Street, circled in green in the map below:

Neville Street can be seen in the bottom right of Booth's poverty map below. The family are living at No 2, which logically means they are living at the end of the street. As we can see in the map, Neville Street is cut down the middle. 'Very Poor' at the north end, 'Mixed, Comfortable' at the south. Unfortunately, in this case, I have no way of telling which end our Charley and his young family are living in - but what do you think?

Domestic arrangements at the Partleton home will soon have to change. Charles might have thought that his army days are over, but he'd be wrong, because war is about to break out...

Possession of colonial land in South Africa had been under dispute for may years between British and Dutch settlers, and on 11 October 1899 this erupted for a second time into the Boer War. Waggy, now 31 and an experienced soldier, signs up and heads off to the war in late 1899 or in 1900.

Back home Susan gives birth to another daughter, Olive, in the April quarter of 1900. Charles is probably not in England for the birth of his third child.

Living conditions for British soldiers in the Boer War were notoriously poor. Here's a picture of British soldiers in the Boer War in 1900 alongside some of their Afrikaner guerrilla opponents. Charles was a rifleman just like these chaps:

Below we see the 1901 census; with Charles away at the Boer War, Susan is Head of the family, including little baby Olive who is now 1 year old:

Susan is living with her children at 32 Cardigan Street, circled in yellow in the map below:

Cardigan Street was owned at that time - and was demolished and rebuilt - by the Duchy of Cornwall. The Duchy of Cornwall is traditionally the property of the youngest son of the monarch - in the present day this is Prince Charles. I thought Susan was in one of these nice houses, but it turns out that they were built after 1901.

The house seen above and below is 51 Cardigan Street from the front and back.

This house is currently for sale (February 2008). The asking price... £565,000. Sharp intake of breath! It only has two bedrooms and 1 reception room... that's yer lot, for a million dollars.

Frankly it wouldn't make much sense for Susan to be living in that nice house, since we know she is absolutely skint, and we can see in the Poverty Map of the 1890s that Cardigan Street is just another blue-shaded poor street:

Here's Charles Booth's opinion of Cardigan Street, exactly at the time Susan is living there:

Cardigan St : East side down except at North & South [We can infer from this that demolition work has started in the middle of the east side of the road] : 2 stories : poor : carmen [carters or railway workers] lb [light blue] as map but less of it [Again a reference to the partial demolition]

Anyhoo, lets cut back to our Charles, who is at this time stuck in South Africa, Boer bullets flying over his head. In the Boer War 22,000 British soldiers died - about one third in battle and two thirds to disease. Thankfully Charles survived; the war ended on 31 May 1902 and Waggy returned home in 1902, but was "unsettled" - a common phenomenon for returning soldiers in any war.

A year later, in August 1903, Susan gives birth to another boy, Charles:

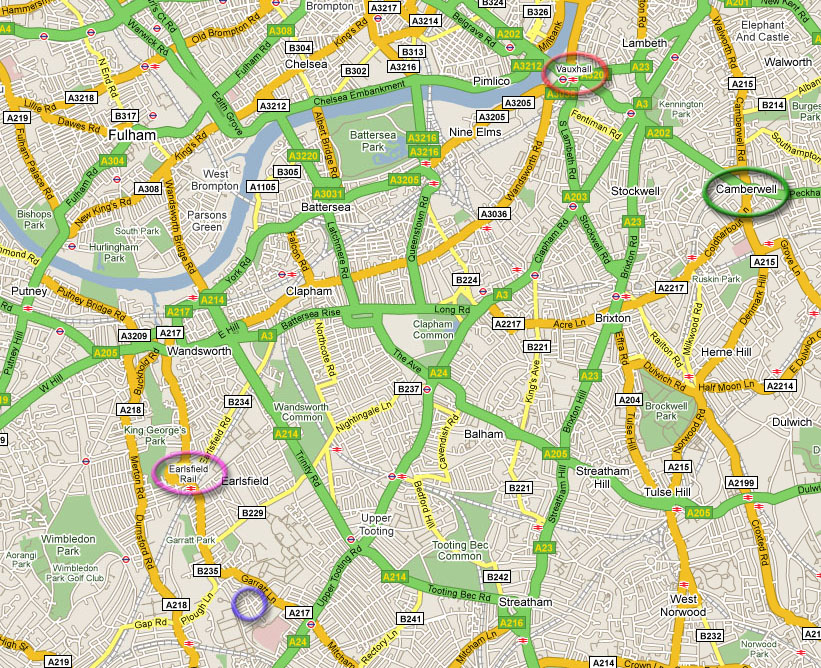

Of considerable significance here is that Waggy has finally left Lambeth. The family have moved out to Wandsworth / Tooting / Earlsfield, circled blue below, which is where the next generation of Wag's family will orbit:

Their new address, Pevensey Road, in the blue circle above, is very much still there today:

Left:

Pevensey Road 2009

Left:

Pevensey Road 2009

It seems Wag may still be commuting to Lambeth for some reason, in which case the obvious route is from Earlsfield Station, circled purple, to Vauxhall Station, circled red.

And it is at Vauxhall Station that Charles, now aged 34, tries to kill himself by jumping in front of a train. On 01 June 1904, Wag's story makes the pages of the Daily Telegraph (this cutting researched by Terry Partleton):

![]()

The incident occurred at Vauxhall railway station, seen here in the early 1900s, exactly as Wag saw it when he decided he'd had enough of the cruel world:

This picture of Vauxhall Station is taken from the viewpoint of the red arrow in the map below:

Here's an annotated transcription of that newspaper story:

Charles Partleton, 34, Army Reservist from the Rifle Brigade was charged with attempting his life by jumping in front of a locomotive at Vauxhall Railway Station.

Henry Hurst, a porter in the service of the South-Western Railway Company deposed that at 12:30 that morning the Prisoner leaped from the edge of the platform and threw himself across the metals, right in front of the approaching light engine. The Witness pulled him off the rails just in time to save him. The Defendant tried to break away, saying, "Why did you not let me do it?"

Left and Below: The Platforms at Vauxhall

Station. Don't Jump!

Left and Below: The Platforms at Vauxhall

Station. Don't Jump!

Defendant [Charles Partleton]: "I thank you now for what you did"

Mr Horace Smith [Magistrate]: "You may well do that, because he saved your life"

Witness [Henry Hurst]: "I hardly know how I managed it, for the engine was right on us. From what I have heard since I think the poor fellow has had a lot of trouble."

The Defendant said he deeply regretted his cowardly act, but he had been overwhelmed with misfortune. Ever since he had returned from the [Boer] War, things had been unsettled, and lately he could get no employment. He had sold up his home and everything he had got, even to his medals, and he had a sick wife and four little children wanting the very necessaries of life.

The Magistrate: "What are you?"

Defendant [Charles Partleton]: "I am a general labourer and handyman of good character. The last job I had was at Buckingham Palace" [He painted the gates; there are quite a lot of them as can be seen in the modern photo below]:

"I finished work there on Christmas Eve [1903], to go home to be laid up with rheumatic fever. I was nine weeks on my back, and since then I have had no regular employment."

The mother [Jane Willcox] and wife [Susan Pirie] of the defendant, both sobbing at the back of the court, were called forward and the older woman, almost overcome with emotion stated that her son had served eight years in India. She was, unhappily, not in a position to help him and she knew that all the chairs went last week to buy a bit of food for the little ones.

Mr Horace Smith [Magistrate]: "The Missionary [a church charity] will see what can be done, and I think that the best thing I can do is to order a remand for a week."

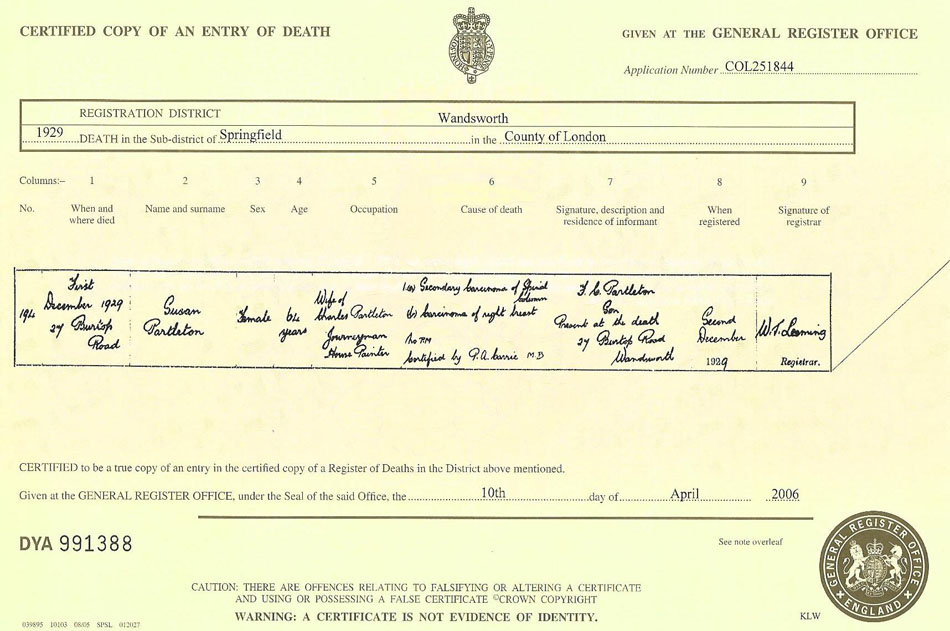

Defendant [Charles Partleton]: "Don't shut me up, sir, for a week. My poor wife has lately been under an operation at the hospital for a tumour in her head. [Susan actually died 25 years later of breast cancer and secondary carcinoma of her spinal column]

Mr Horace Smith [Magistrate]: "I will look after your wife and children while you are away. You can do nothing for them."

The defendant's wife and mother were escorted from the court weeping bitterly.

Left: Vauxhall Station

in 2008 with its striking sculpture!

Left: Vauxhall Station

in 2008 with its striking sculpture!

I've had some time to think about this suicide attempt & I've personally come round to the view that it was a 'cry for help'. A serious attempt would not have offered onlookers any time to leap down on to the rails to foil the effort. You can decide for yourself.

What did Wag think would happen to his little children after he was dead?

Some kindly soul of 1904 organised a collection for the unfortunate Charles, and there were some very generous donations. (A week's rent was about 10 shillings, so 5 shillings was a goodly sum). Below we see the generosity of a number of individuals, including William and Bob Falcon and Jack Hudson, preserved for posterity:

Of note on this document is that Wag is referred to as Wag Miller. Frankly this doesn't help with our understanding of his nickname. Perhaps Wag Miller was a Music Hall comedian? I can find no reference to this name.

We can see that the subscriptions were taken from employees of St George's Baths aka Lambeth Baths, location in 1904 shown in red in the map below, and the G.P.O. [ie Post Office], shown in blue. Why these particular institutions? We don't know, but the fact that they are right next to each other suggests that Waggy was working in the neighbourhood.

Lambeth Baths were quite new at the time, having opened in 1897:

Below is another view of Lambeth Baths, photographed in 1903. In fact, it's possible that St George's Baths referred to on Waggy's document is a different public baths on Westminster Bridge Road. The two institutions are very muddled in the historical record & I can't separate them, so let's just stick with Lambeth Road... somewhere in there, someone is making a collection for Wag:

On 04 January 1945, as we see below, Lambeth Baths on Lambeth Road suffered a direct hit from a German V2 Missile. Wallop.

It seems that Wag regrouped from his failed suicide attempt of 1904, because on 23 December 1906, Susan gave birth to another son, Alfred Ernest Partleton.

This is Charles' last child. The house at this address, 55 Beechcroft Road, Tooting - not far from their previous address at Pevensey Road - is no longer there.

We don't have any surviving photograph of Wag, but perhaps we can get some idea what he might have looked like by looking at his children in the 1930s, so it's a good moment to put up his family tree:

At the birth of his last child in 1906, Alfred, Waggy is still just 38 years old - but he may not have a whole lot more years left.

As mentioned at the beginning of this page, there is no Death Certificate for Wag at the General Register Office, which is very unusual. This means that we will have to get our Sherlock Holmes magnifying glass out to search for tiny clues elsewhere.

On 02 June 2009, Terry Partleton paid a trip to Battersea Library to check out the Electoral Rolls for this period:

The key dates here are October 1914 and the mention of the 1911 census, which we now have.

Below is Charles' original 1911 Census Return, not filled out by an enumerator, but in his own fair hand. He put the girls in the wrong column and then made a correction:

We can see from the declaration at the bottom of the census sheet that there are seven people in the family, crammed into just three rooms - including the kitchen, assuming they had one. The census was held on 02 April 1911.

But the next information we have - the Electoral Roll of October 1914, mentioned in the email above - Susan was at home, alone, as Head of Household. Where was Waggy?

On 16 November 1914, Wag's son Frederick, lying about his age, signed up to fight in WW1:

At the bottom of this Military History Sheet, which was - by all logic - created on 16 November 1914, Frederick gives his next of kin as his father, our Waggy. This is clear evidence that Wag must have been alive in November 1914, apparently at 171 Mitcham Road. But why wasn't he there a month earlier in October when the Electoral Roll was taken?

The 1914 date gives us one obvious idea; that experienced ex-soldier Charley, even though he was now 44, might also have signed up for WW1, which had started in August. But then we would expect to find army records for Charles, and we don't.

Two years later, on 21 September 1916, young Frederick, fighting in France, makes a will:

Frederick names his mum, not his father Wag, as his beneficiary. Perhaps this doesn't signify much.

We've seen the address on that will of 171 Mitcham Road several times now, and fate has recently turned up a photograph of it. We know it's one of the cottages on the north side of Mitcham Road in the picture below, probably the one on the far right, next to the premises of John Cragg Fowls. I can't imagine the Partleton family could afford to rent the whole of this pretty cottage; perhaps just a part of it:

Still we hunt for Wag, but the best clues are being provided by his son Frederick. Frederick was discharged from the army in 1917 for poor health, and in December 1918, with WW1 over, he gets married:

Witnesses to Frederick's marriage are his mum Susan and his sister Olive, but not Wag.

By 1921, it's now 10 years since we have seen Wag on a census or Electoral Roll. But when his daughter Olive is married on 22 May 1921, we are given a fairly decisive clue. Olive's father is declared as Charles Partleton (Deceased).

I find this compelling evidence, but Terry Partleton points out quite rightly that in later years when Waggy's children Charles and Alfred were married in 1928 and 1932, Wag is declared as the father, with no mention of 'Deceased'. You can decide for yourselves if this is significant.

Assuming we believe Olive's Marriage Certificate, then Waggy would have died between November 1914 and May 1921. That's a gaping 7-year range which happens to encompass the First World War.

We are pursuing a couple of paths of investigation to home-in on Waggy. We are fairly sure he was a Chelsea Pensioner (as an out-pensioner) after he left the army. Chelsea Pension records are available at the National Archives at Kew, if you know where to look - which we don't really, but we are making some headway. Hopefully this may furnish us with Wag's addresses through the years and the termination of his pension.

Also, we are having a close look the Electoral Rolls. We know that from 1917 till the 1930s, Susan and her children remain at 27 Burtop Road, long gone, which was off Garratt Lane in Earlsfield, Wimbledon, close to the newly-built Wimbledon Greyhound Stadium in the 1920s.

Wag's wife Susan Pirie passed away on 01 December 1929:

The informant is Susan's son Frederick. Again Charles is recorded as the husband without a mention that he might be deceased. I don't think this is significant, and it's my view that he's dead, but you can make up your own minds. He'd only be 61 at this date.

Finally, a reminder of what Susan looked like.

Three of the above portraits are lifted from a single photo sent to the Partleton Tree by Heather Partleton in Australia. Before that we had nothing.

Sooooooo..... We don't know what happened to Charles 'Wag' Partleton [yet], but we do know that he has at least 121 descendants; grandchildren; great-grandchildren, great-great-grandchildren. In fact, he probably has 200+ descendants since the family tree is far, far from complete in the female line. Most of these descendants are alive and kicking today. Someone out there must have some more pictures - not just of Wag but any, pre-war.

Who's got dusty old pre-war family photos in a shoebox somewhere? We all have! So, c'mon - dig them out, blow the dust off and email them in, even if you don't recognise who is on them!

Meantime, the hunt for Wag goes on! If you want to see the tracks we are pursuing, click here to view Wag's addendum.

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... or would you like to discuss any of the history... or if you have any observations or comments... all information is always welcome so why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'In Their Shoes' Page.