Charles 'Wag' Partleton (1868-bef1921)

Charles 'Wag' Partleton brings 'In Their Shoes' to one of our puzzles. Though he had at least 25 grandchildren, most of whom are still alive, nobody - nobody - has any idea when or where or how Waggy died. To be fair, most of those grandchildren were born after 1921 when we believe Wag may be dead, but you'd' think maybe just one of their parents would have told them what became of their granddad.

And we still can't find a Death Certificate for Charles, which is very unusual, though perhaps not quite so surprising when you read the story of his life and his character.

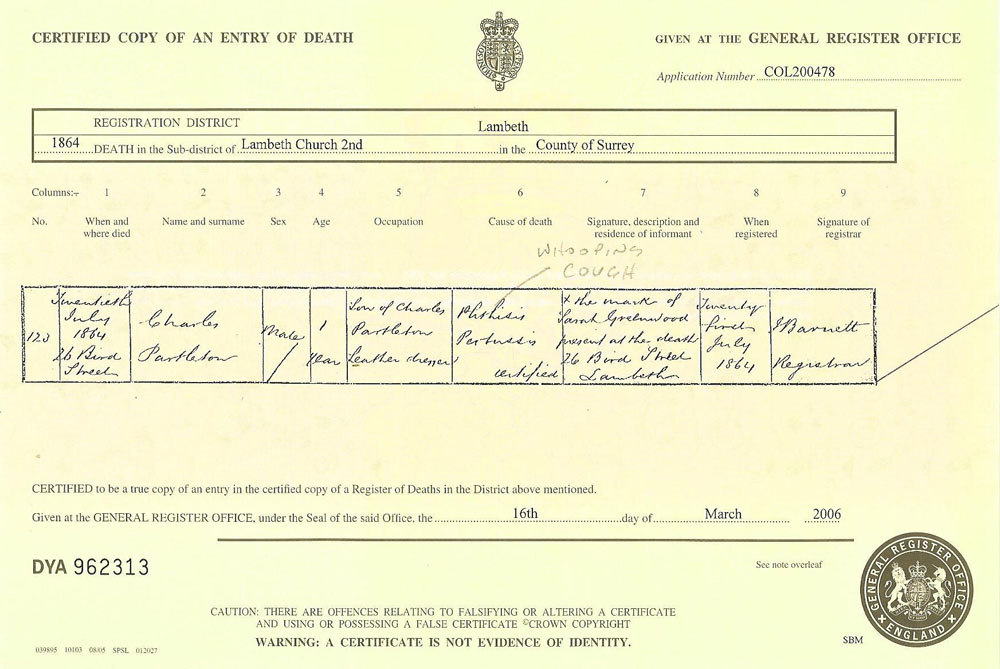

Charles George Partleton was born in July 1863, at 26 Bird Street, Lambeth, the first of nine children to Charles Greenwood Partleton and Jane Ann Willcox... but hold on... this is not our Wag. This Charles died on 20 July 1864, aged 1, of whooping cough.

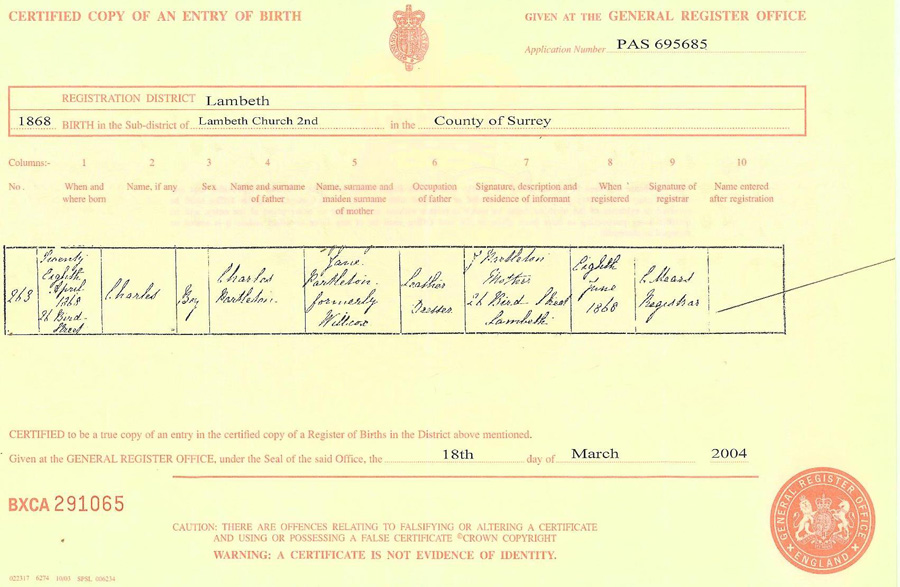

Two more children come, Marion (1864) and William (1866) before another boy is born on 28 April 1868 and the parents again decide to call the baby Charles. Giving a child a name that has already been given to a previous child which has died may seem strange to our modern sensibilities, but the Victorians did it all the time.

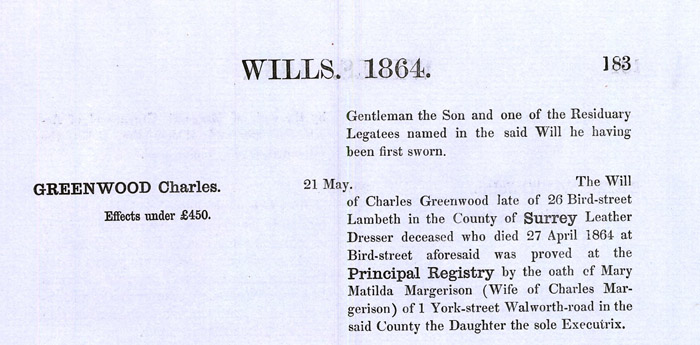

Baby Charles' dad - Charles Greenwood Partleton - had been made an orphan at age 13 when his mother Mary Greenwood had died in 1856, and consequently Charles Sr had been brought up in Lambeth by his mother's family, the Greenwoods. It is in the former home of the the baby's great-uncle - Charles Greenwood (1793-1864), at 26 Bird Street, Lambeth - that little Charles is born.

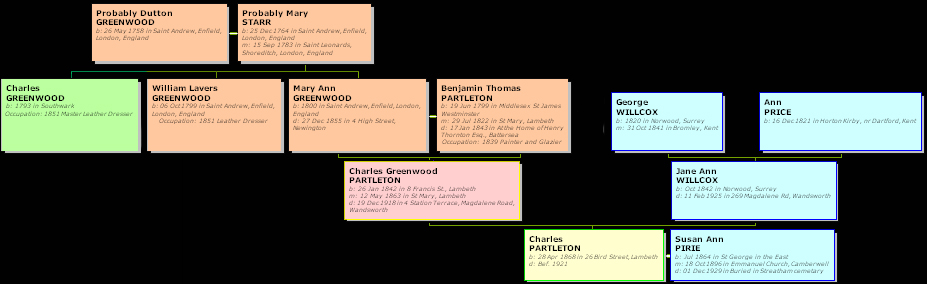

You may have experienced a slight swimming sensation in your head while reading that last sentence since there are too many Charleses with very similar names. Here's a tree which may help:

Charles Greenwood Partleton (b1842), orphaned at age 13, shaded pink, was raised for some years by his uncle Charles Greenwood, shaded green. Widower Charles Greenwood had been around in 1863 to see the first baby [the one at the top of this page] born in his home at 26 Bird Street, but he died in 1864:

His nephew Charles G Partleton is still living at 26 Bird Street in 1868 and it is at this address that our baby Charles, shaded yellow, was born.

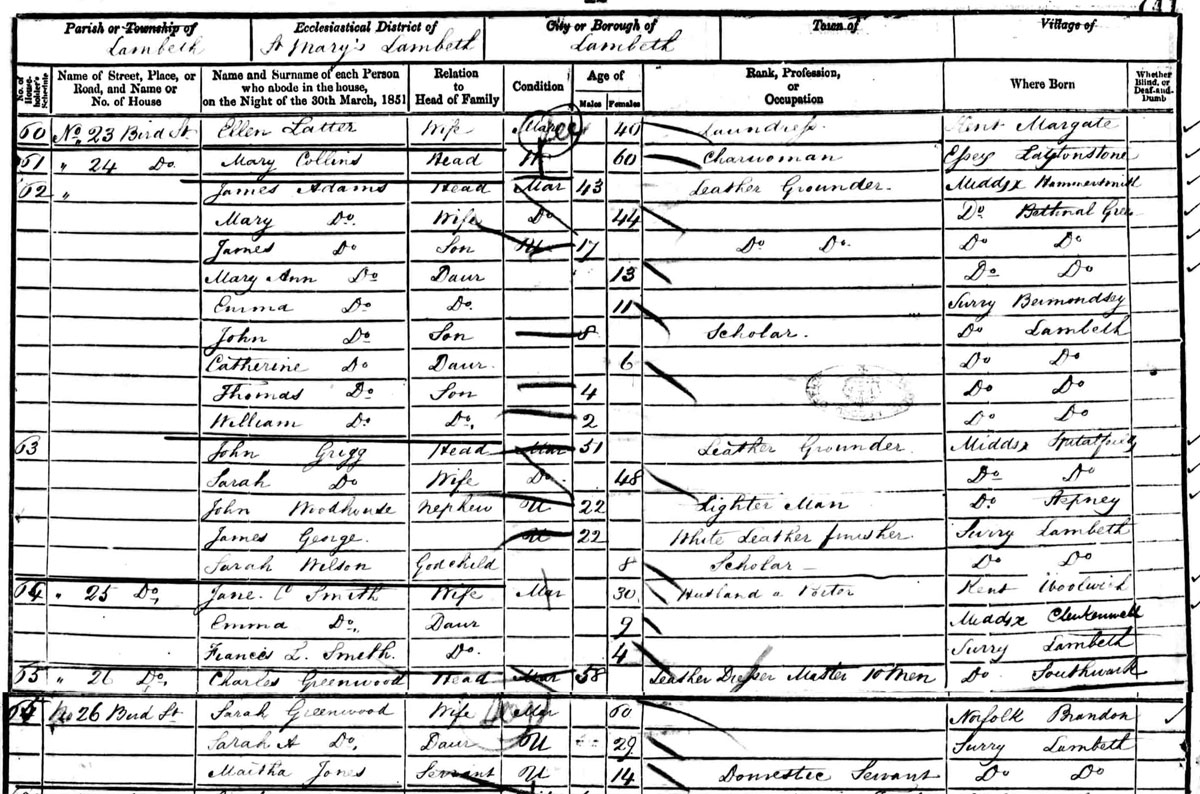

The Greenwoods had been, in a working-class way, comfortably well off. They'd been at Bird Street since at least 1817, and If we look at 26 Bird Street in the 1851 census, we find Charles Greenwood, 'Leather Dresser, Master of 10 Men' and employing a live-in maid:

Leather-dressing involves scraping the fat and hair off animal hides - which have been soaked in stinky chemicals - with a curved blade held in both hands. It's a smelly and unpleasant job, but it's a living, and it's the same profession which occupies our Charles' dad, Charles Greenwood Partleton. The illustration of leather-dressing below was painted in 1805 by William Miller:

I'm not sure Charles Greenwood Partleton would have worked in the open air like these chappies. In Lambeth I think it would more likely have been in a factory.

Let's take our bearings. Bird Street is at the point of the green arrow in the map of Lambeth below:

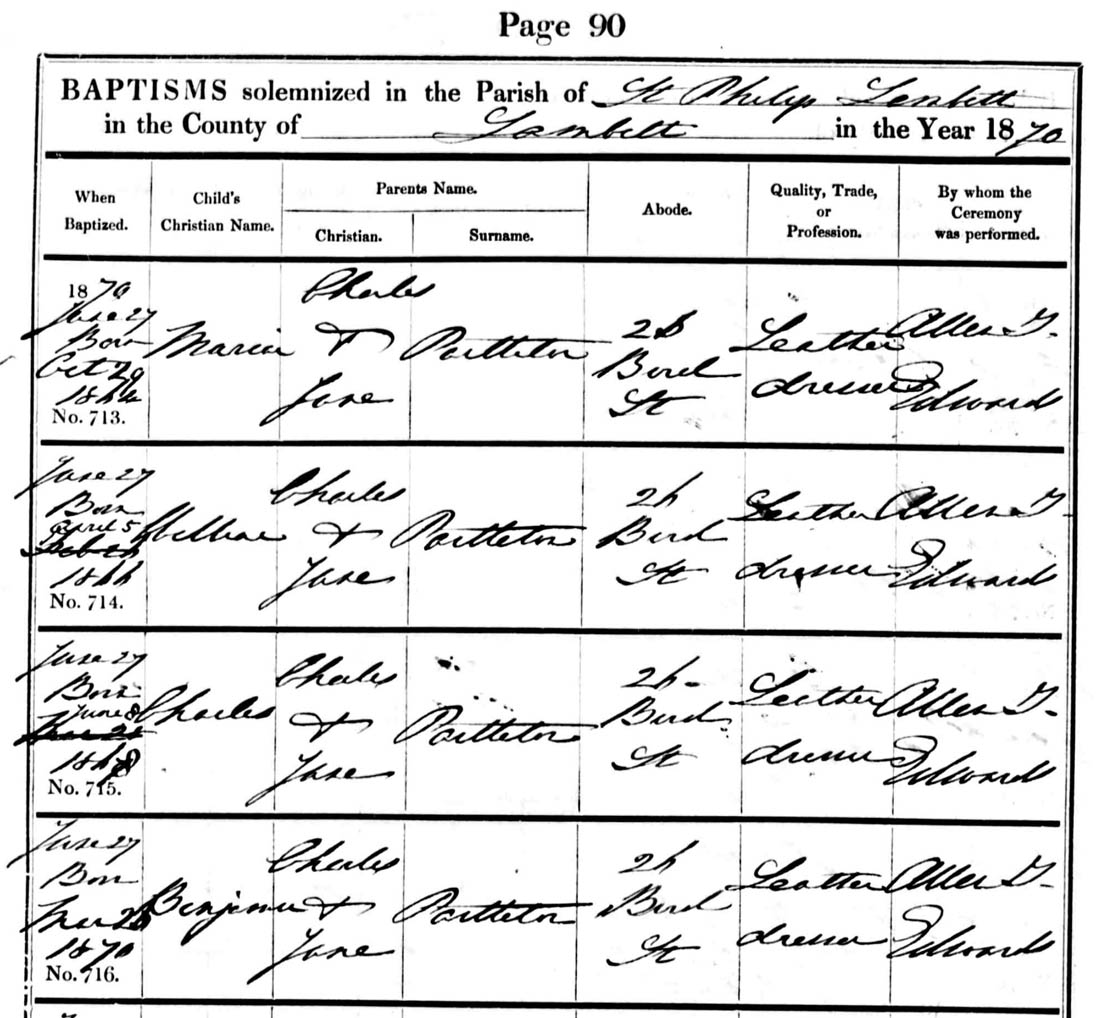

When Charles is two, his parents take him to church to be baptised:

The parish register gives us the clue that Charles' parents - Charles Greenwood Partleton and Jane Willcox - probably weren't particularly religious as they used the birth of their new baby, Benjamin, to catch up on the christenings of their other three kids, Marian (b1864), William (b1866) and our Charles (b1868).

The family was still at Bird Street, which turns out to be in the parish of St Philip Lambeth. This illustrates how quickly things are changing: the church is in the orange circle in the map below...

...except that this is Stanford's map which was drawn in 1862, and St Philip's wasn't built until 1863, so it's not shown.

The church was demolished in the 1960s. Here's how it looked:

Let's have another look at Bird Street in the map:

In the 1890s philanthropist Charles Booth visited Bird Street and found that it had prostitutes hanging around the housing at the end of the road, as we shall see shortly.

Watching MTV a few Sundays ago, I realised that, for the June 1982 filming of the video for Come On Eileen, Kevin Rowland and his dungaree-bedecked Dexy's Midnight Runners were flouncing around at the end of Bird Street. Here they are, at the end of the video, from the viewpoint of the blue arrow in the map above; Bird Street is the turning on the left:

If you have 3 minutes 48 seconds to spare, you might enjoy seeing the streets of 1982 in the video; some of the buildings quite familiar, I'm sure, to young Charles Partleton, some of them perhaps slightly later than 1871. Click the Play button in the box below to watch:

Vi's Stores seen in the still on the right above, are at the corner of Hayles Street, from the viewpoint of the red arrow in the map below:

In 1871, if you lived on Bird Street, as Charles did, you could hardly miss the fact that you are residing right behind the world's oldest and most famous lunatic asylum - the Royal Bethlem Hospital - seen below looking south from the viewpoint of the yellow arrow in the map above - better known by it's shortened form of name: Bedlam...

The hospital had relocated to Lambeth in 1815 from Moorfields inside the London City walls. It was at Moorfields that it picked up its terrible reputation of being a public attraction, a freak-show for which the public would pay for entry to gawp at the inmates, many of whom were chained, as depicted by William Hogarth in 1736:

The new hospital at Lambeth - the one just around the corner from our Charles, was very different; aimed at curing its patients - as much as medical knowledge of the day would permit - and at least tried to offer as much comfort and compassion as possible. There were no chains in the new Bethlem; even straitjackets were banned after 1851.

Here's the corridor inside Bethlem which accessed the female wards:

And here's a ward:

The main gates:

What remains of the Bedlam building at Lambeth is now home to the Imperial War Museum... But let's get back to Charles and his birthplace; Bird Street.

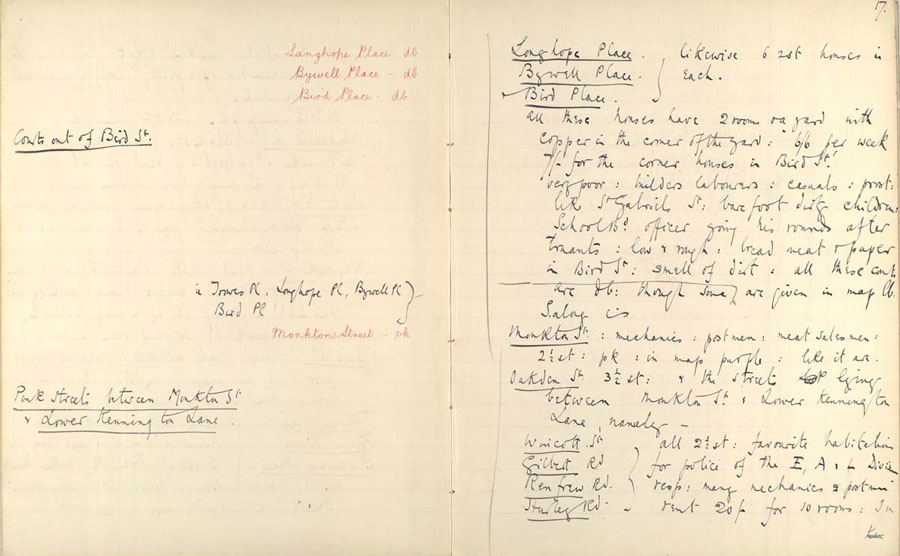

Bird Street is not the most auspicious of places to start your life. The street is poor, and the courts which lead off it - Birds Place, Princes Place, Hope Place, etc are even poorer. But don't take my word for it; let's seek the opinion of a man who actually walked down Bird Street in the late 1800s and took some notes for his famous Poverty Map of London; Charles Booth.

"Bird Place [one of the courts in Bird Street] : All these houses have 2 rooms + a yard with copper [a clothes-washing vessel] in the corner of the yard : 6/6 [6 shillings and 6 pence] per week 7/- for the corner houses in Bird St. : Very poor : builders labourers : casuals [paupers]: prostitutes : like St. Gabriels St. : barefoot dirty children : School Board's officer going his rounds after truants : low & rough : bread meat & paper in Bird Street : smell of dirt : all of these courts are db [dark blue] though some are given in map lb [light blue] :..."

What did Bird Street look like? Well, surprisingly, one small piece, on the corner with Walcot Square, has survived - though it looks very much like it has been repaired from the second floor up. That might have been WW2 bomb damage, which would explain the careless matching of bricks as a hurried post-WW2 patch-up.

Bird Street is the road branching off to the left:

We are looking from the viewpoint of the green arrow in the map below. I'm fairly sure that this corner shop, and perhaps the three adjoining buildings on Bird Street, were there in 1868 when Charles was born.

And some parts of the neighbourhood are even better preserved. The road branching to the right of the photo is Walcot Square, see the purple arrow below:

The whole of Walcot Square was built by a charitable trust in 1837-1839 and has been under watchful control ever since. If you choose to live here, you won't be able to paint your front door without someone's permission. And if you want a satellite dish, you can forget it!

The photo below is of the north side of Walcot Square, from the viewpoint of the purple arrow, and certainly presents exactly the same image to your eyeballs as it did to Charles in his childhood. These houses, shaded pink in Charles Booth's poverty map, are significantly posher than the one our Charles lives in:

So we've established where Charles was born - 26 Bird Street. Soon afterwards, his dad Charles Greenwood Partleton decides it is time time for his young family to move away. Perhaps the lease is up, or maybe it's too expensive.

The family aren't moving very far... in the 1871 census, with Charles nearly 3 years old, we find them living at No 13 Bird Street. The Partletons are lodging in the premises of widow Eliza Wrangle, 'Gold Size Maker'. Curiosity got the better of me here, so I looked it up. Gold size is glue made from gelatin, used as an adhesive for gold leaf:

This seems a good opportunity to decode some of those funny marks which we see on the 1871 census sheet. A double slash, highlighted by the red circles above, indicates a house separated from its neighbours. So we see No 13 Bird Street enclosed within its double slashes. A single slash such as we see in the blue circle, separates single rooms within a building.

From this we can tell that Charles' entire space for living and sleeping is just a single room shared with his mum and dad and his three brothers and sisters. And very soon it is to become four because his mum Jane is fairly heavily pregnant at the time of the census, which was held on 02 April 1871. In May of 1871, Charles gets a little baby brother, Harry Partleton.

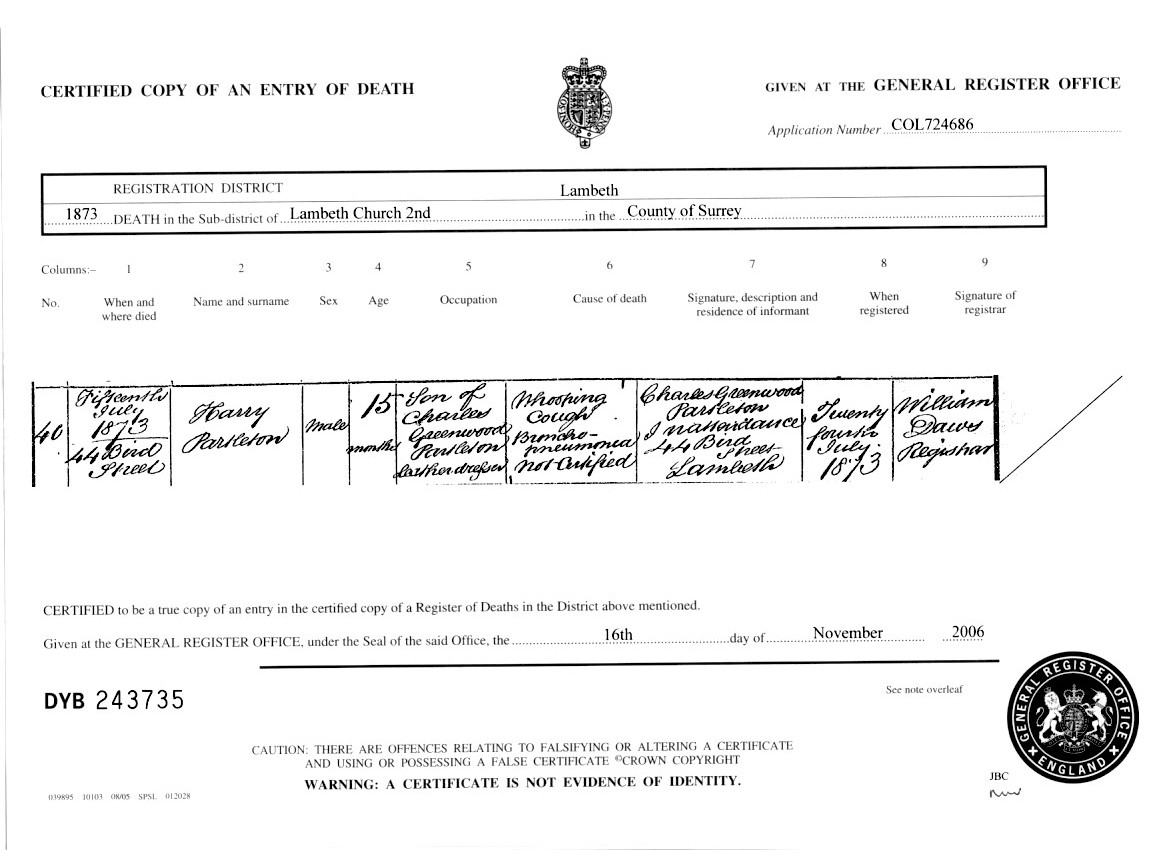

15 months later, 15 July 1873, Charles is now five; his new baby brother Harry catches whooping cough and dies:

Harry's the second baby in the household to fall to this disease, ten years after the first. Note that the family have moved yet again, but it's not exactly a big adjustment for little Charles; they're still in Bird Street - now it's number 44.

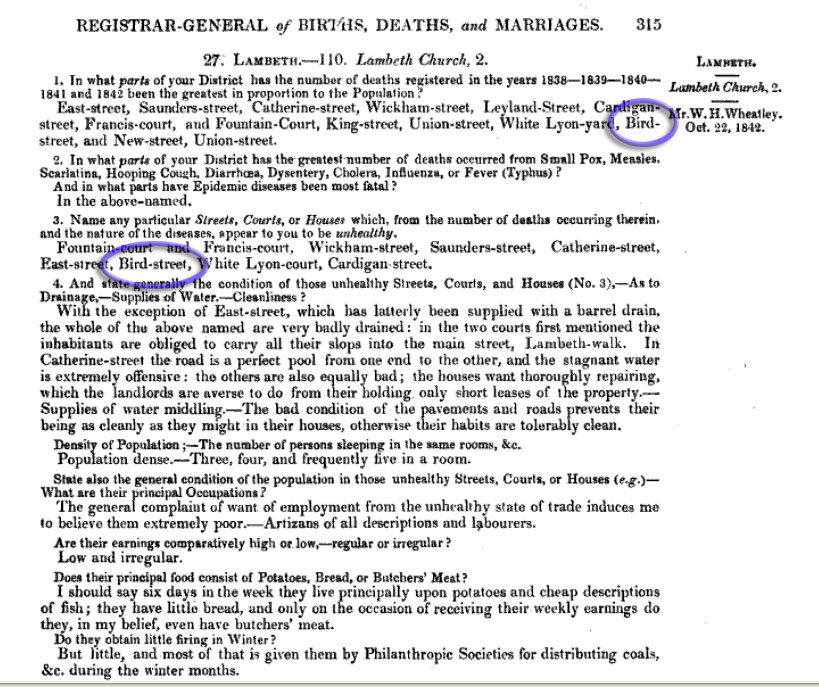

And we learn more about poverty and death in Bird Street in The Annual Report of the Registrar-General for England and Wales:

This report was published many years before Waggy was born, but it shows us that, for decades, even in a poor borough like Lambeth, Bird Street was one of the poorest streets.

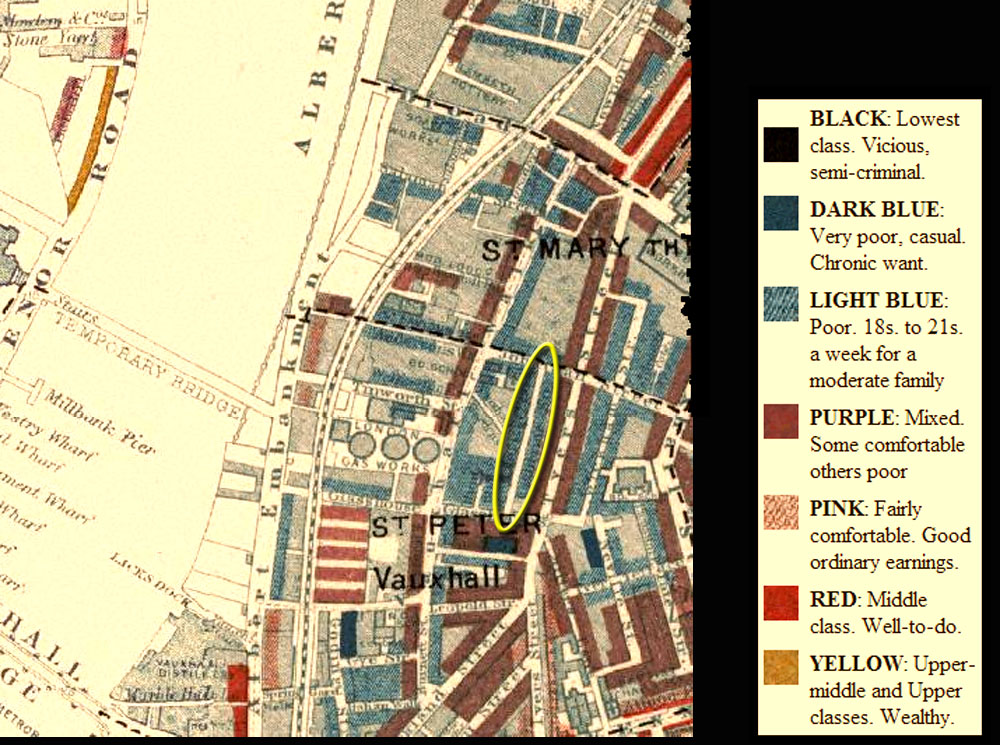

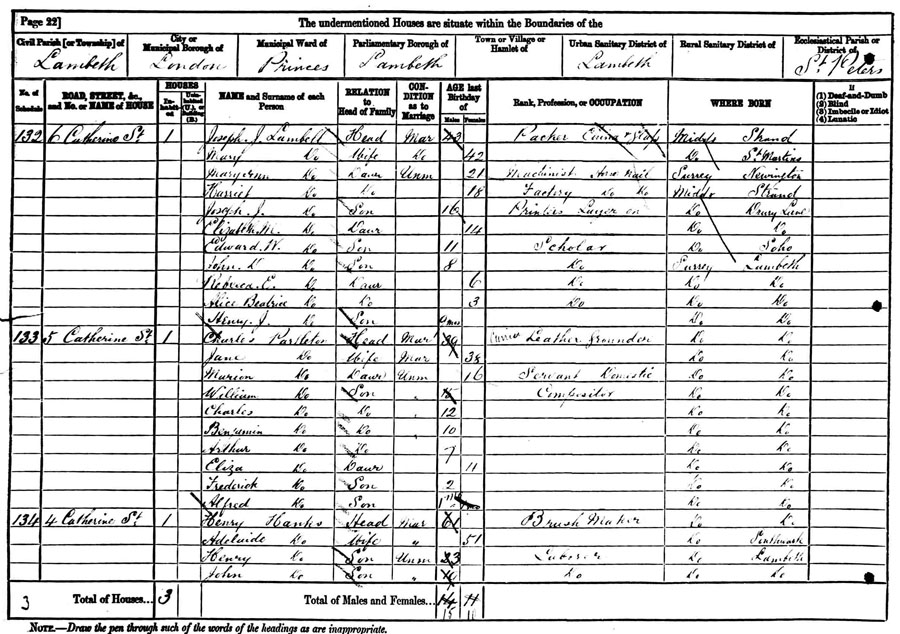

And so we move on to the 1881 census, where we find that the family has moved a mile or so south, to Catherine Street in the centre of Lambeth, circled yellow in the poverty map below, near the gasworks. Catherine Street was shaded by Charles Booth as light blue, meaning that it is poor, but perhaps it's an improvement on Bird Street...

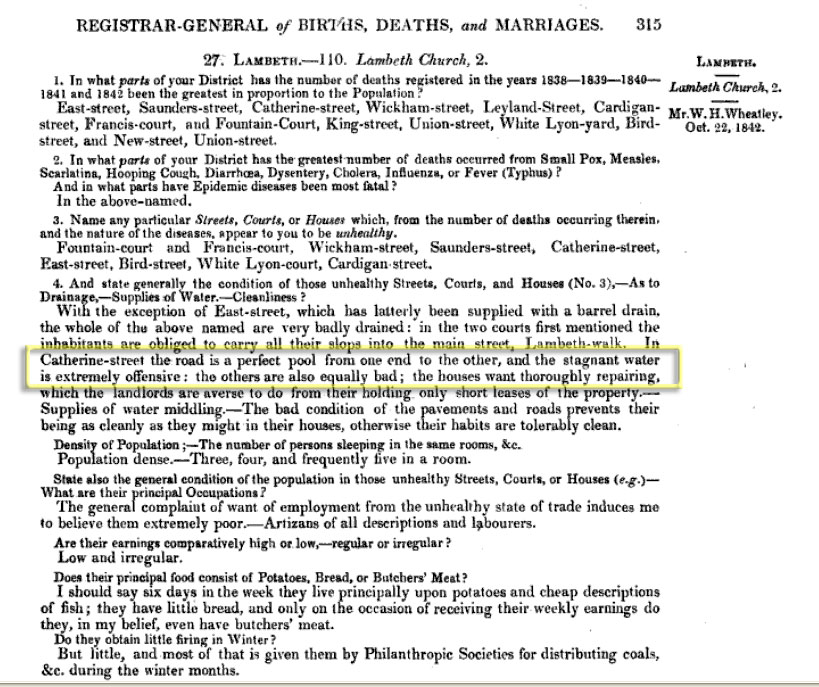

... but actually, on the contrary, in the same report, we learn that Catherine Street was also listed as one of the most unhealthy streets in the borough; indeed, as highlighted in yellow, there was no sewer, and the open drain which ran down the centre of the road had become a long, single, stagnant pool of human waste:

The Victorians, from the mid-1800s onwards, undertook programs of sewer-building, so it is possible that by the time Wag lived in Catherine Street, he may not have had to play around foetid puddles of excrement.

Let's hope the house in Catherine Street is a bit bigger than the one in Bird Street, 'cause there are now eight kids:

If you're wondering where all those census records came from, I can tell you that you'll find them in the extraordinary database of original scans held by Ancestry.co.uk. And if you're inspired by this website to seek out your own British ancestors as I have done, click here.

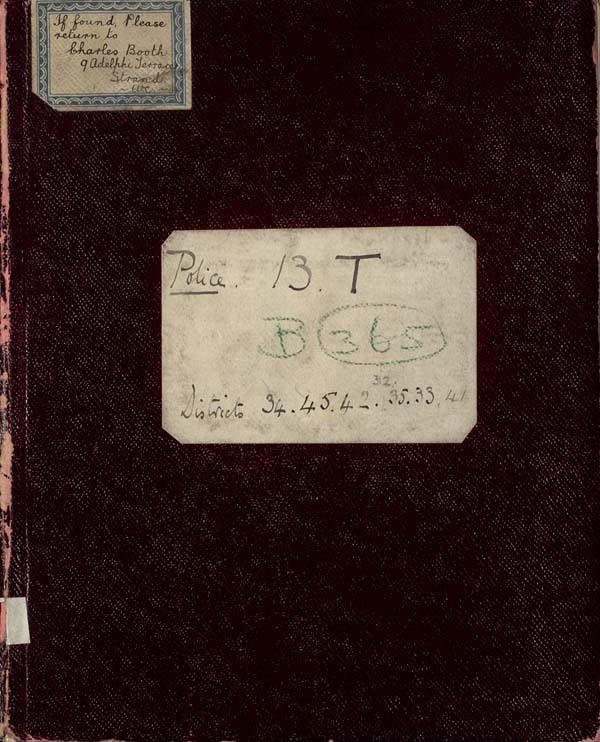

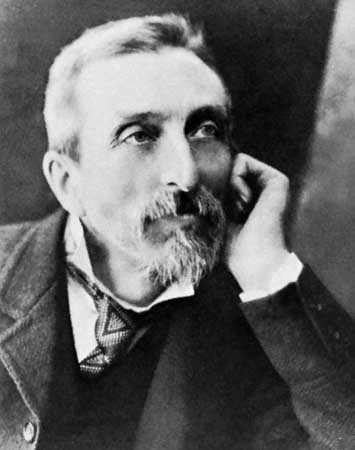

Let's get Charles Booth's original notebook out again, and while we are at it, have a look at the great man himself:

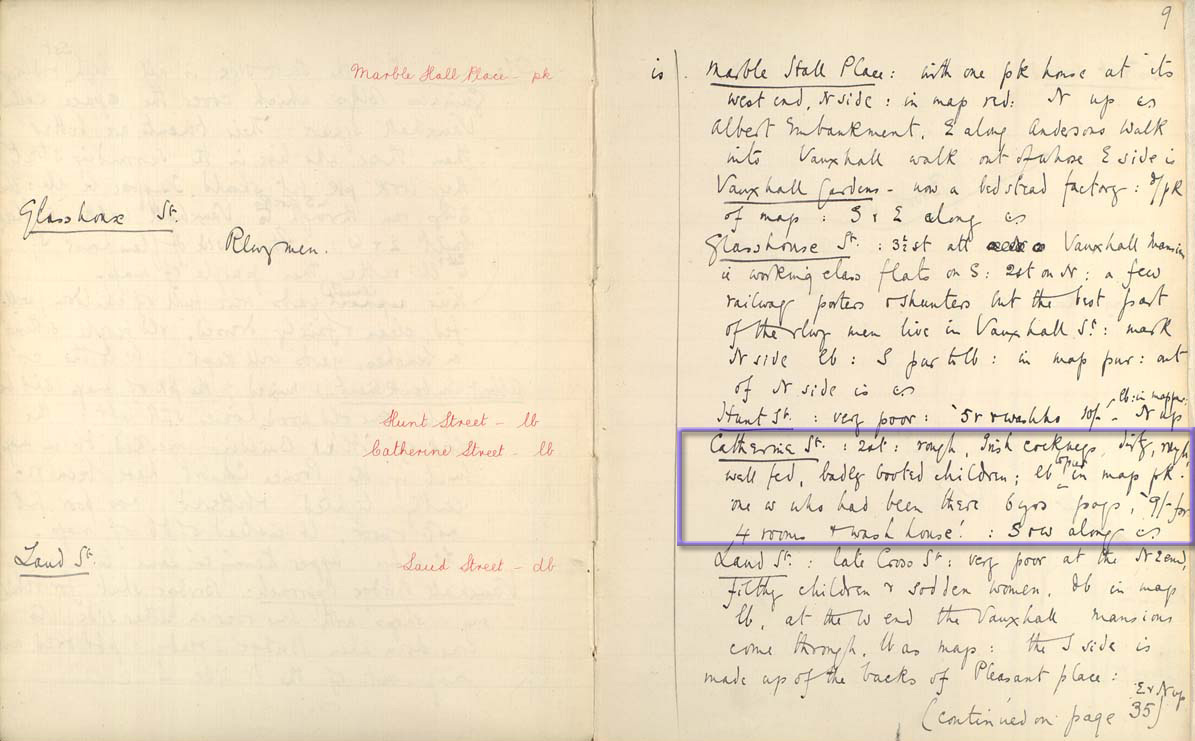

Here's Charles Booth's evaluation of Catherine Street:

Catherine St : 2 stories : rough, Irish cockneys, dirty, [illegible], well-fed, badly-booted children : lb [light blue], in map. One who has been there 6 years pays 9 shillings for 4 rooms & wash house.

Catherine Street can be seen more clearly, circled in blue the map below:

The proximity of the house to the London Gasworks, circled purple, is the most obvious geographical feature of the location of Charles' new home. The introduction of gas street-lighting to London in 1815 and, subsequently, gaslight in houses, created an unstoppable demand for coal gas in the 1800s. But it had to be extracted from coal, by heating the coal till the vapour comes out - a smoky and pungent process. Where to locate the gasworks? Somewhere near enough to central London to allow coal to be shipped in and gas to be piped to the houses?

London's industrialists stroked their chins... "How about Lambeth?" ... "Why Lambeth?" ... "Well, it already stinks like Beelzebub's underwear, so one more smell won't make much difference." ... "You're right. Spot of lunch?"

Gustave Doré, the genius Frenchman who engraved pictures of London's dark underbelly in the 1860s and 70s captured this image of working conditions in the Lambeth Gasworks exactly at the time Charles is living in the neighbourhood:

![]()

I've used so many of Monsieur Doré's pictures on this website, I think we should have a look at the artist. Here he is c1857 exhibiting a certain Gallic je ne sais quoi:

The gasworks also allows us to locate 12-year-old Charles' whereabouts in early photographs of the area.

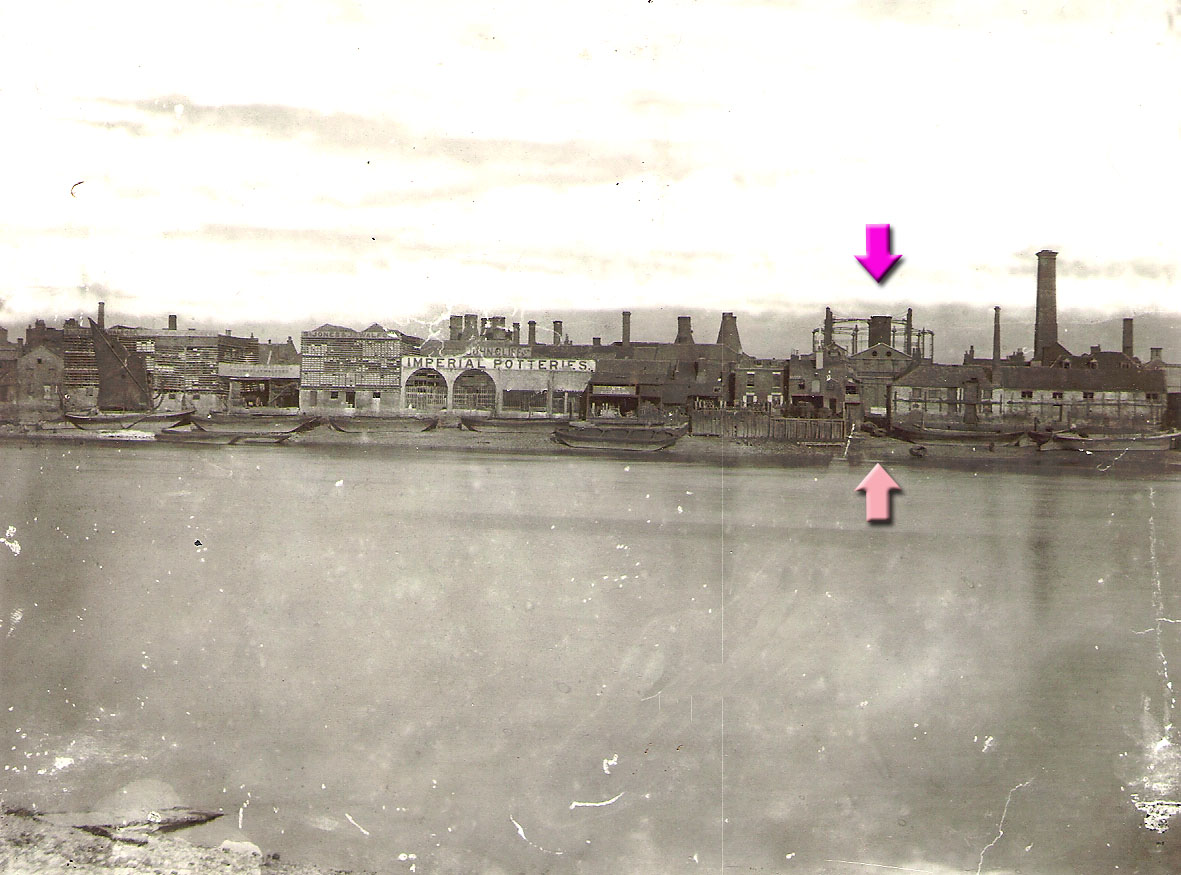

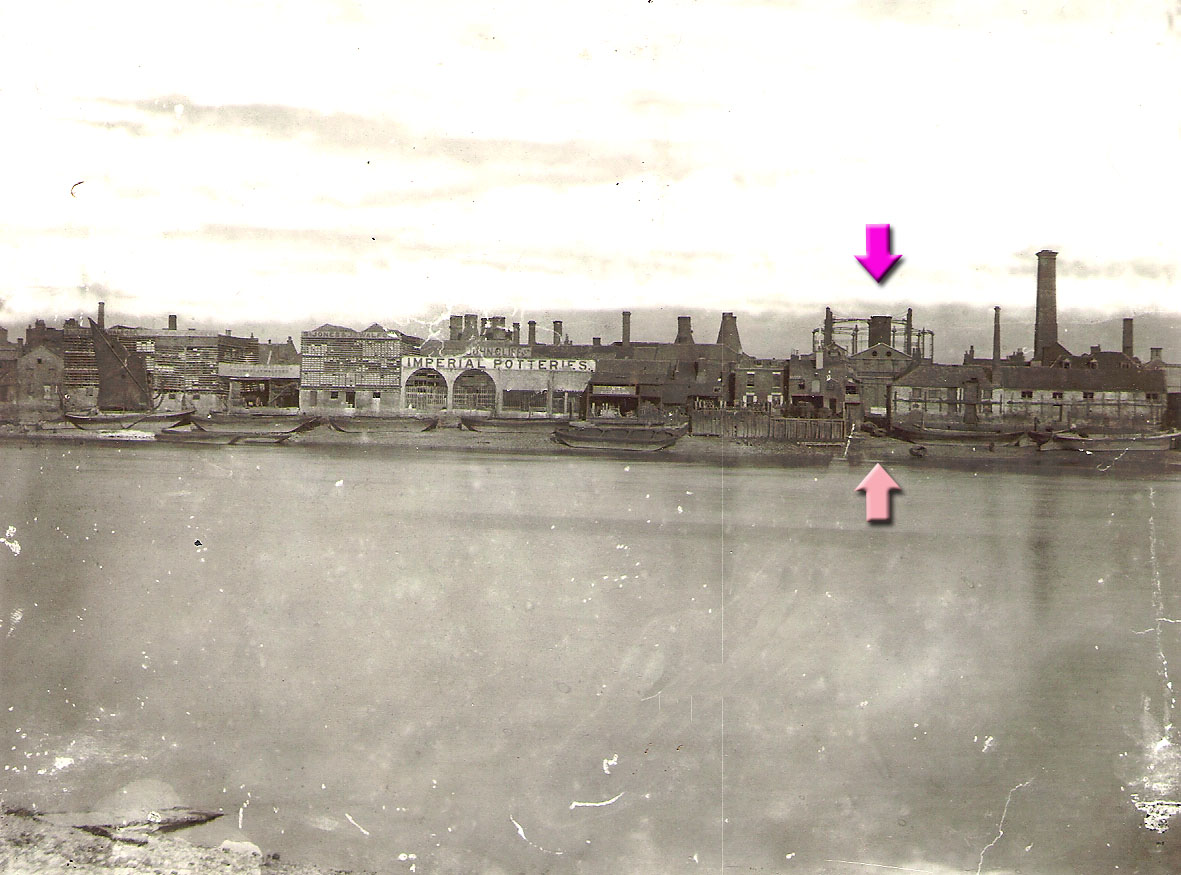

Here we are, transported back to the 1860s. We stand at the riverside at Millbank and point our camera across the Thames to Lambeth... Click! Or rather... (1) set up tripod very rigidly; (2) stick your head under black blanket and fumble large glass-plate negative into camera in the dark; (3) gently remove lens cap; (4) stand very quietly for 100 seconds and trust that you have the exposure right; (5) hope nothing moves; (6) replace lens cap; and (7) stick your head under black blanket and fumble large glass-plate negative out of camera in the dark; Voila!:

The result is a huge negative commonly 6.5 x 8.5 inches, sometimes even bigger, with a higher resolution that you get with a modern digital camera!:

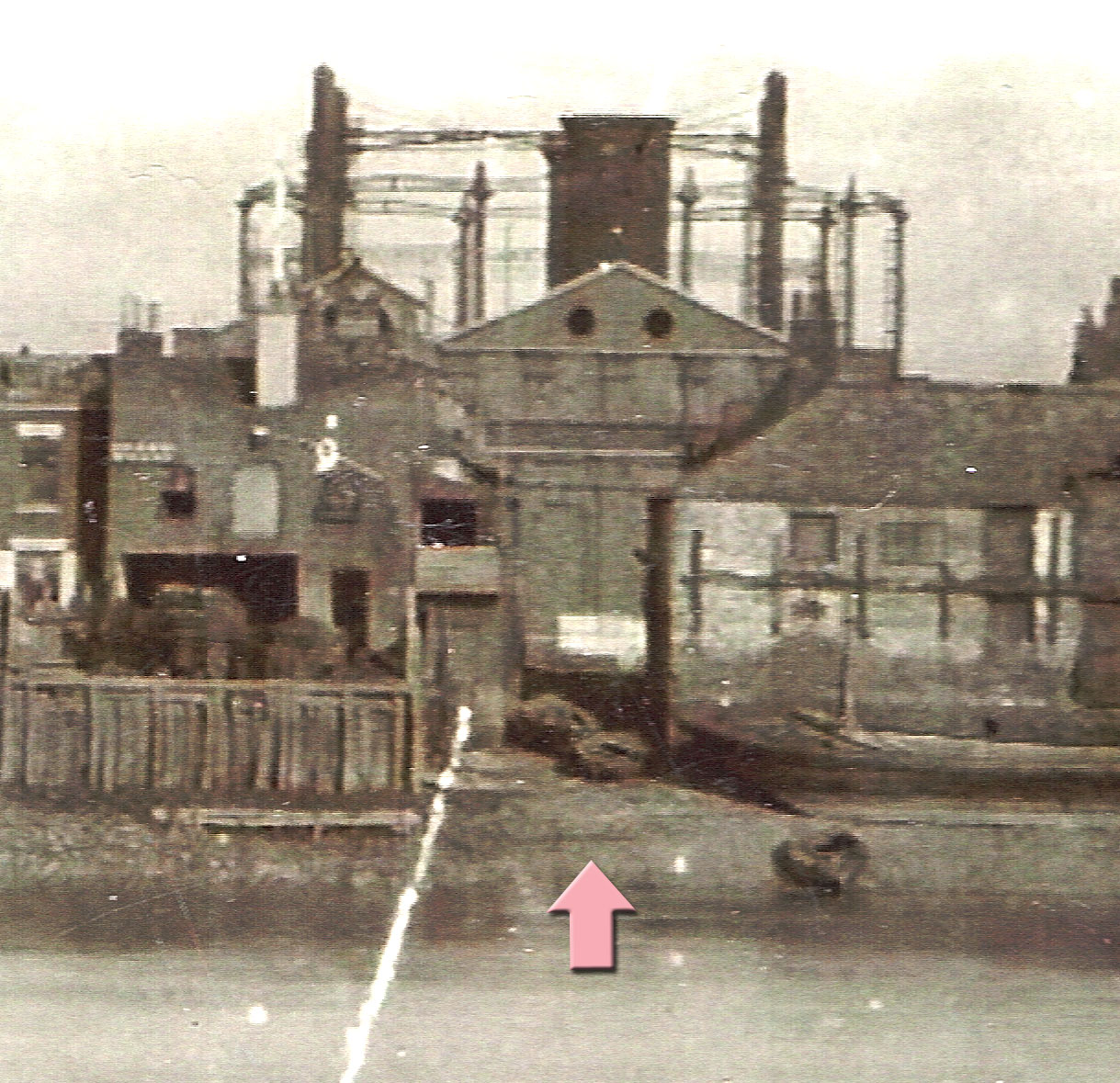

The photograph above was taken from the viewpoint of the turquoise arrow in the map below. The photographer, who may have been Richard Strudwick, stood with his back to the formidable walls of the Millbank Penitentiary. Charles' home in Catherine Street is behind the steel structures of the gasholders picked out by the purple arrow in the photo.

And here's another view. We are standing on Lambeth Bridge looking south, from the viewpoint of the orange arrow in the map, and we see our now-familiar gasworks in the smog in the distance at the point of the purple arrow. 12-year-old Charles is out there somewhere. Step into his shoes:

But let's just go back to that first view across the Thames because it's a good excuse to use my favourite photo a little further down the page:

Coal to fuel the gasworks surely came in by train, as we see it adjacent to the railway, but some coal may have been transported by river, in which case it will come in at New Street coal wharf, which we see circled in pink in the map below, and identified by the pink arrow in the photo above.

Lets zoom in across the Thames to New Street wharf, as much as my print of the original photo will allow:

This little wharf on New Street frankly doesn't look like it would handle very much coal; not enough for a gasworks. It's where you went to buy coal for your fire at home.

If we cross the river and stand in New Street, looking back towards the Thames, we see the coal wharf at the end of it; the Nag's Head pub, Clayton & Glass Coal Merchants, and the biggest Red Ensign flag ever, in this watercolour of c1850:

The towers which we see in the distance on the other side of the river are those the dreaded Millbank Penitentiary, where - among other things - criminals held for transportation to Australia were incarcerated whilst awaiting their ship.

But we have one more picture of New Street in the 1860s before we drop the frankly limited subject of gasworks:

Yes, I know you may have seen it before, but it's got to be worth another viewing! Welcome to Charles' world! See those kids - that's exactly how he looked.

At this point, our Charles is about to go missing from the records, so it's the perfect time to discuss his nickname, oft-repeated down the years; 'Wag'

The original version of this page carried a bit of an appeal to anyone who could cast more light on the nickname. We get perhaps one email a week from the general public, and in October last year, we received an email from Gary Thorogood who passed on this useful information:

My mum, Joan Partleton, when speaking about our Charles, who was her long-dead granddad (he'd died years before she was born) would always refer to him simply as Wag, not Charley Wag, but of course, his name was Charley, so this whole nickname has a ring of truth. And the email also prompted Terry Partleton to recollect that when he was at school, when someone was playing truant, this would be referred to among the kids as having 'gone off Charley Wag'.

Then in February 2009, we were contacted on the Partleton Tree guestbook by Lisa Barr who confirmed to us that Charles - who is her great-granddad just as he is mine - was indeed known in her family as Charley Wag.

So we need to go in search of the origin of Charley Wag, and that leads us to an interesting diversion:

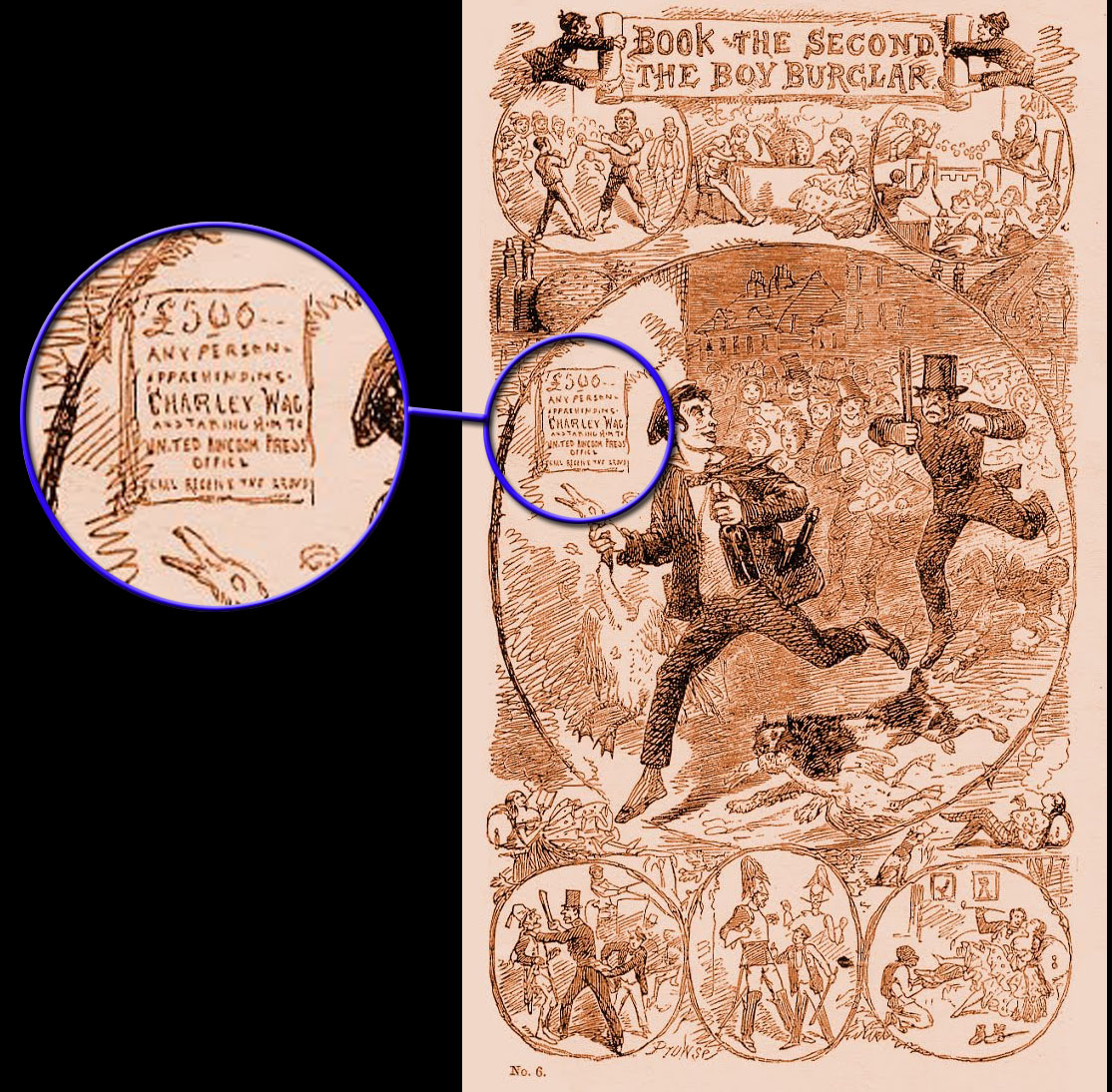

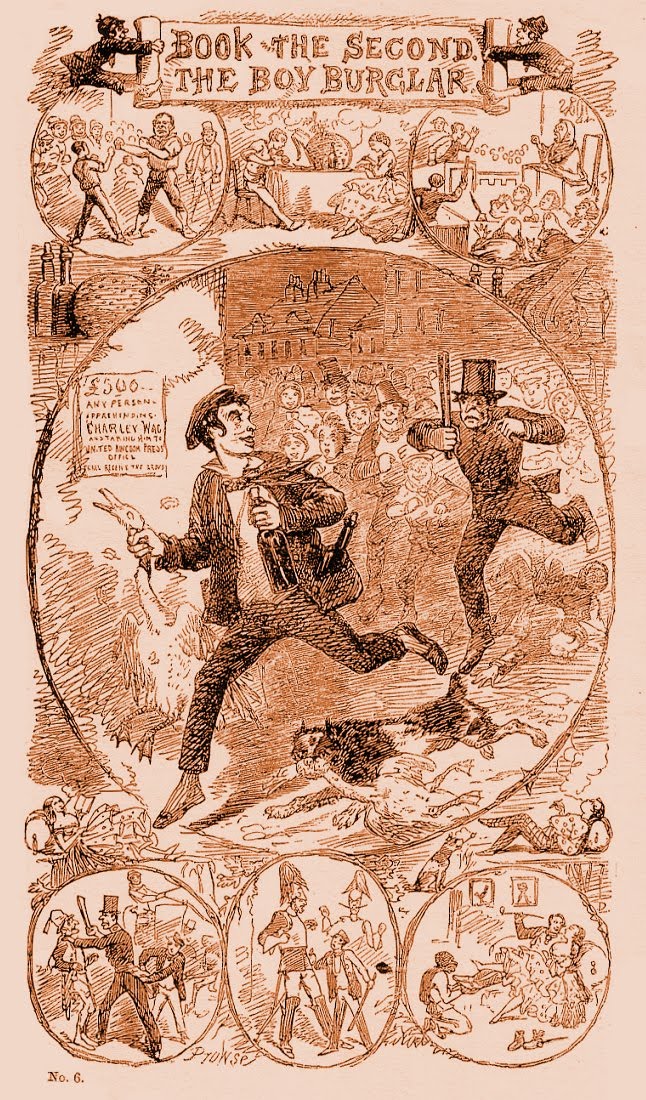

What we see above is the front cover of a popular Victorian Penny Dreadful. This was a term applied to nineteenth-century British fiction publications, usually lurid serial stories appearing in parts over a number of weeks, each part costing a penny. Penny Dreadfuls were printed on cheap pulp paper and were aimed primarily at working-class adolescents.

Working-class boys who could not afford a penny a week often formed clubs that would share the cost, passing the flimsy booklets from reader to reader. Other enterprising youngsters would collect a number of consecutive parts, then rent the volume out to friends.

Let's go back to that cover, which I found in a publication called DisreputableiPleasures by MikeiHuggins and J AiMangan. The hero of this particular Penny Dreadful, titled 'The Boy Burglar' is none other than the original Charley Wag, depicted running away, laughing, from a copper having stolen two geese and two bottles of booze. An appreciative crowd cheers him on. Behind him is a 'WANTED' poster offering a £500 reward for his arrest. This specific Penny Dreadful was very well-known at the time, and was first published in 1860 - eight years before our Charley was born.

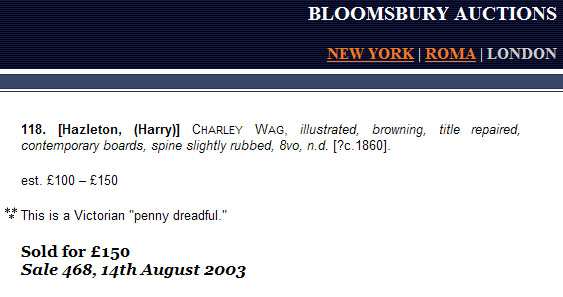

I innocently entertained the notion that I might buy a copy of a Charley Wag Penny Dreadful, for my research, for a couple of quid on Amazon or Ebay, but it turned out that I was being optimistic:

In spite of the fact that hundreds of thousands were published, the books were very flimsily produced on the cheapest possible pulp paper, and consequently very few indeed have survived. There were 240 old pence in the pound, so the book at the auction above sold for 36,000 times the cover price of one of the magazines!

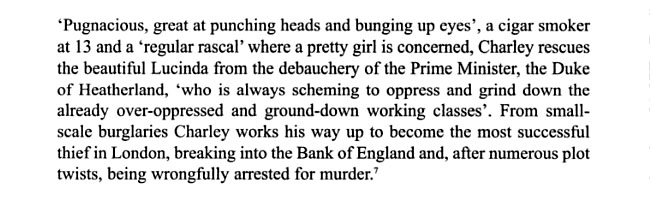

The fictional Charley Wag was abandoned by his mother as a baby; she flings him into the Thames. But he's rescued by Mr Toddleboy, a shambling alcoholic, who raises him, but not very caringly. By the time he's 13, Charley's spending his time truanting from school, smoking, drinking and stealing from houses. He's an unlikely-sounding hero, but the point is that he represents the oppressed, the underclass - the readers - cocking a snook at the Victorian establishment. He only steals from those who deserve it.

And of course he has his redeeming features; he's a joker; a charmer; a likeable rogue, as summarised by MikeiHuggins and J AiMangan, and we learn a little of the bizarre plot:

As a result of the success of this publication, the name "Charley Wag" in Victorian times could be applied to any young fellow who might be a bit of a chancer, a comedian, a character, a truant, a charmer, a rebel, especially if their name happened to be Charley. Below is a snippet from Charlie Chaplin - a CentenaryiCelebration by PateriHaining

So, does this give us any insight into the character of my great-granddad Charley Partleton? From what I have been told, the characterisation could certainly apply to his son, my granddad Frederick, whom I never knew. As for Charley, I certainly don't want to defame a dead man, but (the rather thin) family oral history has it that he loved to take a risk, indeed could be egged-on to take excessive risks, and was to some degree an alcoholic. That is of course, hearsay, and should be understood in that context. Sorry, Charley, if I got that wrong.

Anyhoo, aside from hearsay, we know some facts for certain. One of which is that his life is about to take an abrupt change of direction.

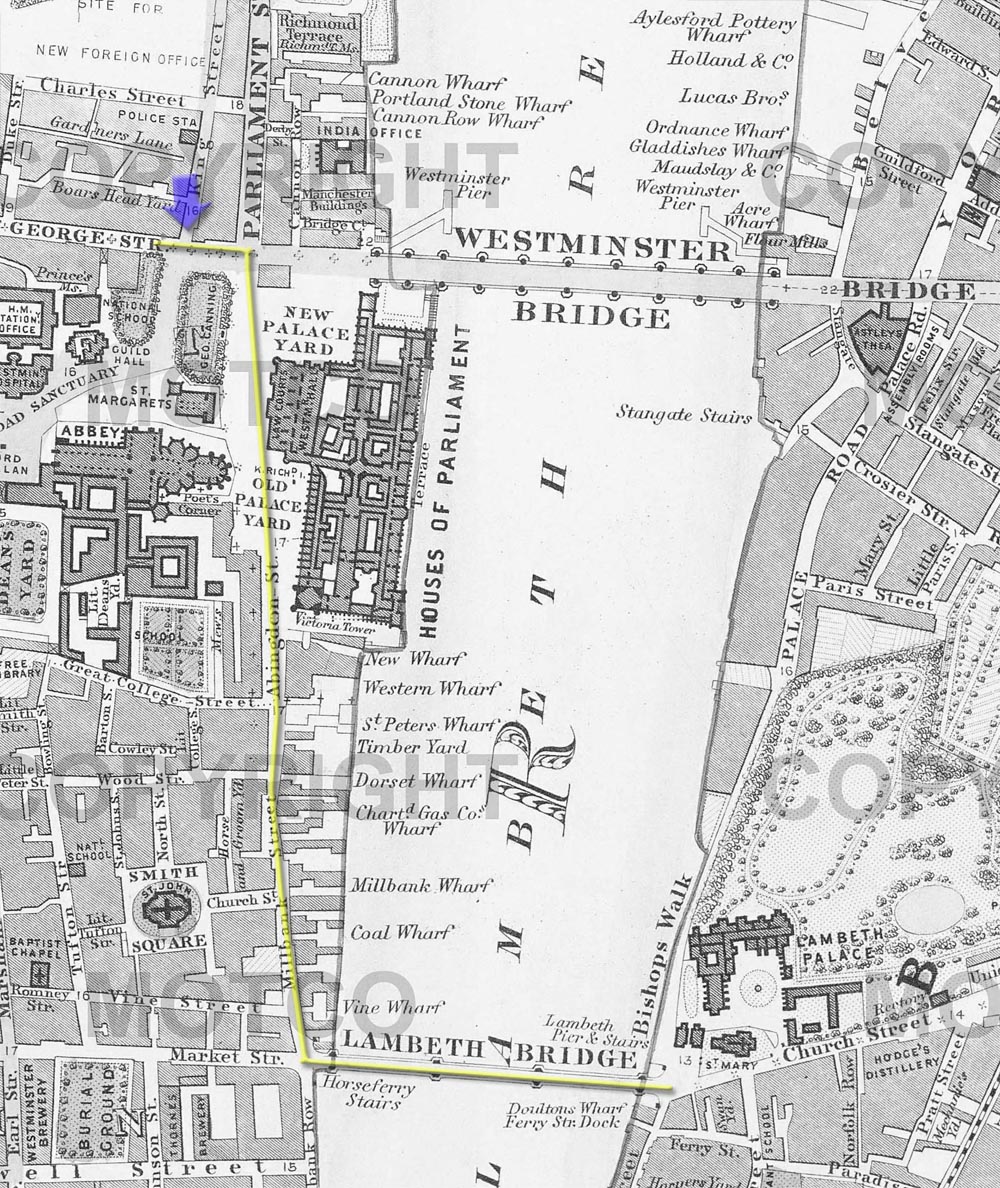

So, let's step into Waggy's shoes and use our imagination for a bit. He's 19 years old and perhaps he's been in town for a few pints with his mates. Heading home, his intended journey to Lambeth will take him through Westminster along the route shown in yellow.

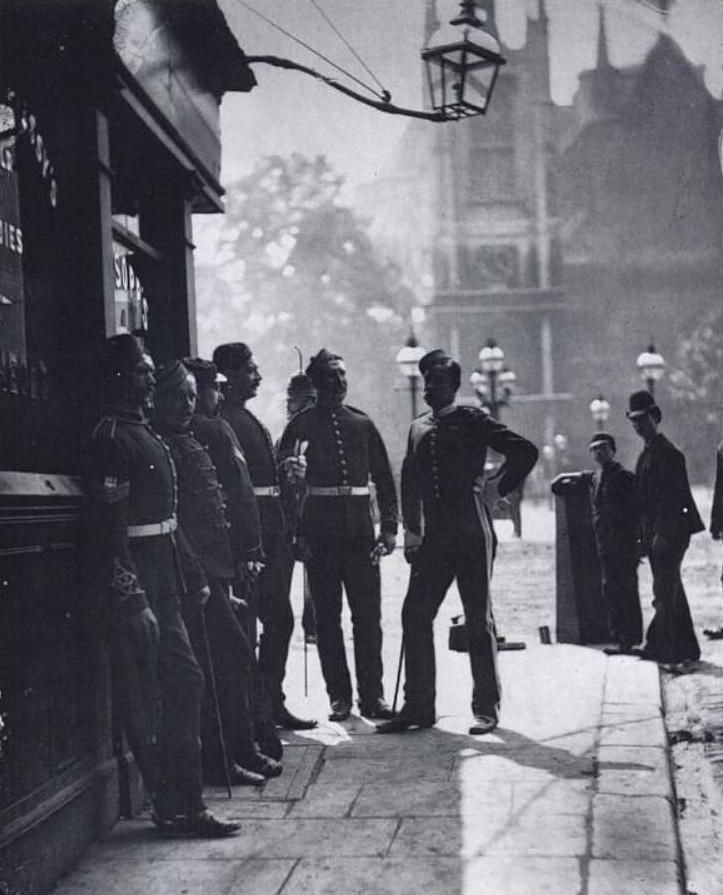

In the photograph below, you are an invisible observer standing outside the Mitre and Dove pub on the corner of King Street. Your viewpoint is that of the blue arrow in the map above. That's St Margaret's Church in the background which you can also see in the modern inset. A young man wearing a Derby hat enters the picture from the right... could this be our Waggy? Actually, no, because that chappie is a boot-black. So.... who are these military-looking punters hanging around outside the pub?

If you were a young man walking in this area through Parliament Square in the 1870s and 1880s, you would unavoidably be stopped in your tracks by one of these gentlemen. That's because they are in fact Recruiting Sergeants for the British Army, well-known characters, the same men working this patch for many years. The soldier furthest right is Sergeant Thomas Ison [whom I looked-up in a census - he actually resides in King Street] and his pals nearest him, Sergeants Titswell and Badcock. No, you haven't suddenly started reading a script for a Carry On movie, those are their real names.

So, Waggy is approached in a friendly and disarming manner by the Recruiting Sergeant; "Have you ever considered a career in the army, son? Why not come into the pub with me & I can tell you about all the fun of it over a couple of pints... you'll enjoy comradeship, travel, adventure..."

There was a tempting inducement of a shilling paid immediately when you signed on the dotted line - "the King's Shilling" - and the Recruiting Sergeant got £1 commission for every recruit who passed their medical. If you changed your mind after signing-up - let's say you woke up the next morning in a cold sweat; "What have I done?" - there was a way out. Waggy didn't change his mind - but if he did, there was a 96-hour cooling-off period during which you could buy yourself out again. That cost £1, a lot of money - compare the paltry pay on offer to the new recruit, which was £18 a year. A labourer in London would earn £40 to £50 a year.

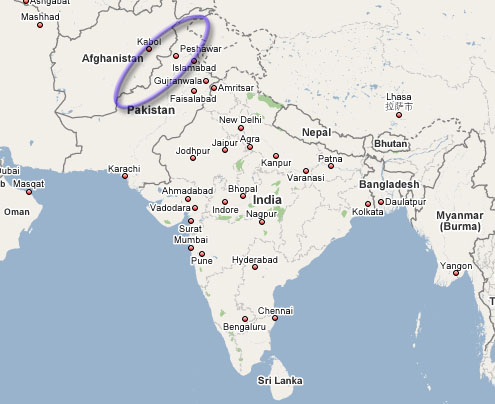

I'm not saying that Waggy was persuaded by a Recruiting Sergeant, but it was the commonest method, and it gave us all the chance to see that great photo. Whatever way he was recruited, we know straight from his mother's mouth, under oath, that he was posted to India where he served eight years, but unfortunately she didn't say when. I plotted the timeline of dates of his life, and by my calculation he must have gone to India in 1887 when he was 19, returning in 1895 when he was 27, give or take 1 year.

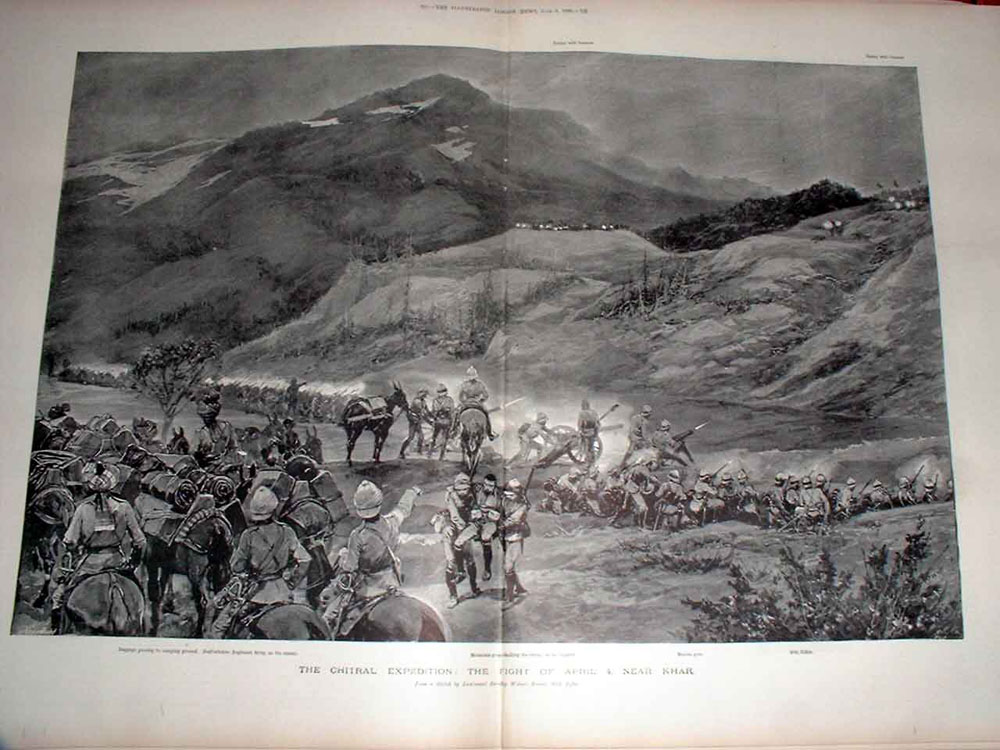

This is the era of the skirmishes on the border between India and Afghanistan known as the Northwest Frontier. Charles is probably involved in this, but I stress that this is speculation. We don't have any information at all on what Charles actually did in India, but let's try to step into his army boots:

Below is the British Army in action on the Northwest Frontier in the year 1891:

Here's where we are:

The border with Afghanistan was fixed by treaty in 1893, but the fighting didn't stop. The illustration below is the year 1895:

It's a pity we can't say any more about our Charles' adventures in India, but we just don't have any information on this. We're working on it.

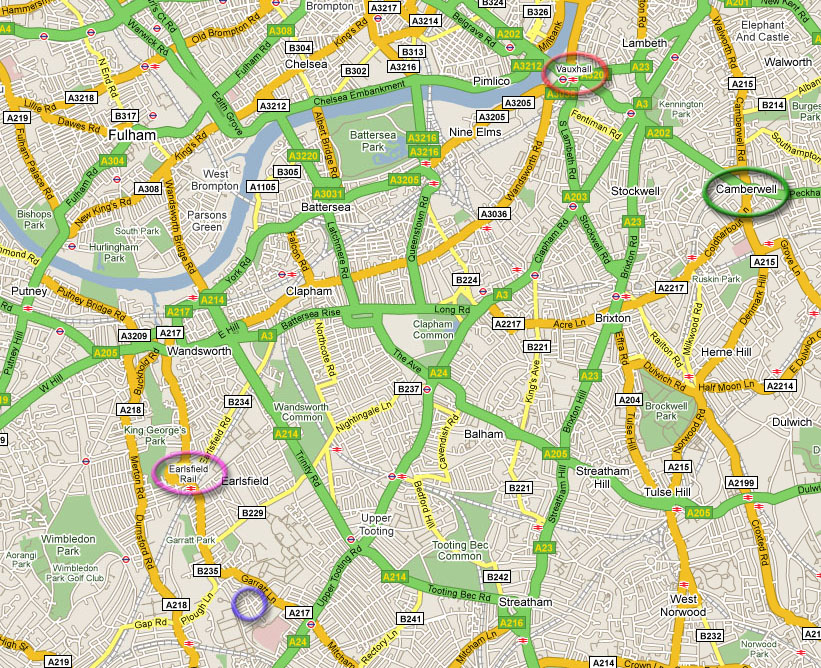

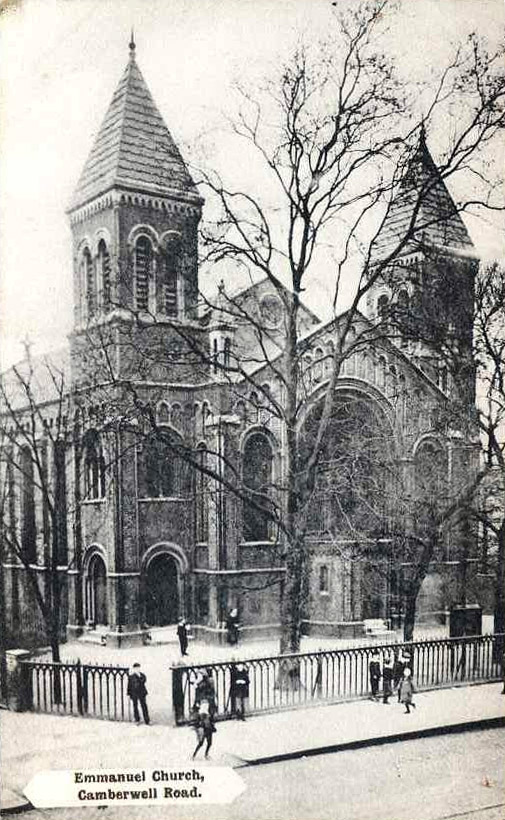

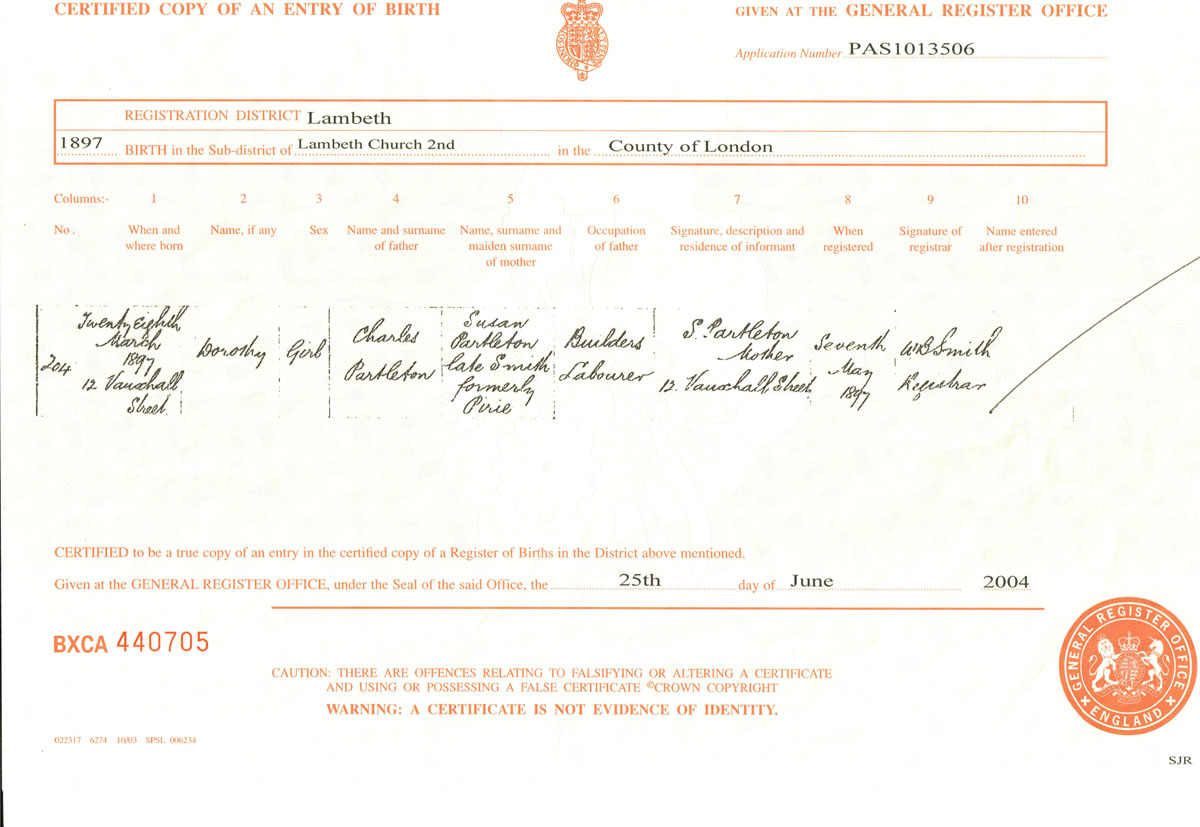

By 1896, we know he is back from his 8-year duty, because in July of that year he gets a Lambeth girl, Susan Pirie, pregnant, and on Sunday 18 October, they are married at Emmanuel Church, Camberwell, London.

Susan, originally from the East End of London, is a widow with two children of her first marriage, Rosetta and William Smith.

My great-grandmother Susan is the first of my ancestors to have their photograph preserved; here she is (in the 1920s):

Have a squint at the 'residence' given on their marriage certificate. Even though it's written twice, and looks quite neat, it's difficult to read - the family historian learns to curse handwriting - but just like the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, it has been deciphered. It's 27 Badsworth Road. This is in Camberwell, circled green below, a couple of miles from Lambeth, and it's my guess that this is Susan's place.

A funny thing happens as we approach the year 1900. Some bits of London suddenly start to look extremely familiar. 27 Badsworth Road - which was almost new in 1896 - still exists today, picked out by the yellow arrow below:

That's a very recognisable style of house to anyone who grew up in South London, as I did. The house is outlined in yellow in the 1895 map below. The photograph is from the viewpoint of the yellow arrow:

The wedding takes place at Emmanuel church which is seen in the c1905 photgraph below, taken from the point of view of the green arrow in the map above, at the junction of Blucher Road and Camberwell Road.

Emmanuel church was demolished in c1965.

As already mentioned, Susan was pregnant aas she walked through the church gates we see above. Five months later, her third child, and Charles' first - Dorothy, was born.

Now that Wag is married, he and Susan are heading back to Lambeth, so this seems a natural point to break off this excessively large page and continue the story with a fresh one.

Click here to go to Part 2 of the story of Charles 'Wag' Partleton.

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... or would you like to discuss any of the history... or if you have any observations or comments... all information is always welcome so why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'In Their Shoes' Page.