Catherine Partleton (1810-1895) in 1826

Part II

This page is a continuation of Part I of the story of Catherine Partleton. Click here to return to Part I.

To summarise: Catherine Partleton had been born in Westminster in 1810 and had appeared as a young actress on the London Stage. She was married to shoemaker James Cunningham in 1832 and set up home in a poor part of Southwark, London.

Catherine and her husband James appeared in the 1841 UK census, and had children up until late 1848, but they cannot be found in the 1851 census or any subsequent record. Did they die? What became of them? Why do they disappear from the record? It seemed to be a dead end.

But in July 2007, the Partleton Tree website received an email from Terry Bigler who lives in Corydon, Indiana in the United States:

Here's what Terry was able to direct us to; a ship's passenger list of March 1850:

Incredibly, what we see in the above document is the departure of Catherine Cunningham nee Partleton from the shores of England, bound for New Orleans, never to return. With her are her five children; James, Hannah, Martha, David and Jane who is just a baby. Also travelling is Catherine's young brother-in-law, Walter Cunningham, aged 20.

They sail on the good ship Soldan [an archaic spelling of Sultan]. This is the era before steam-powered ocean liners: the Soldan is a square-rigged sailing ship, and not a particularly big one. There are just five families on board - The Ashleys, the Pages, the Lawrences, the Cunninghams and the Dobles. I couldn't find a picture of the Soldan, but here is a passenger vessel departing Britain bound for America in 1853:

The Soldan had been built in Medford, Massachusetts in 1841 by the firm of Sprague and James and had been ferrying emigrants across the Atlantic from Liverpool and London to New Orleans since at least 1843. I found this mention of her in a maritime review of 1846:

We see from the ship's manifest that Catherine has all her worldly possessions packed into five boxes. Her husband James Cunningham had already sailed to America in December 1848 on board the Forfarshire (Click here to see the passenger list). No doubt, much letter-writing has ensued, and by 1850, he has cleared the way for the family to follow.

If we put on our Sherlock Holmes hat and puff on our pipe, we can unearth great deal of evidence about the circumstances of Catherine's sailing across the great Atlantic Ocean in 1850. The first comes from a very interesting book published in 1855 by Frederick Hawkins Piercy, who was a Mormon:

It's a guide to emigration called The Route from Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Valley, and in it is revealed the cost of a journey across the ocean in 1855 :

What we see above is the cost of passage from Liverpool to New Orleans in 1855: Departing from London, as Catherine did, would have cost a little more, but let's assume that she has managed to secure the cheapest tickets. One adult and four children; total cost £15 10s. Catherine's baby daughter Jane goes for free.

Was that a lot of money? We learn from the Reading Mercury of Saturday 19 May 1849 that shoemakers might typically earn 3 shillings a day:

Thus, Catherine's husband James was earning about 18s for a six-day week; they were poor - money was tight. Let's assume they might have 20% of that to spare. In that case they would have had to save every single spare penny for two years to pay for those precious tickets.

So come on, let's pack Catherine's five boxes on a cart, depart Catherine's home in Southwark, and make our way to the London Docks. The most likely route from Southwark would surely be across London Bridge and down the Commercial Road. It's about 5 miles:

We don't know which specific dock our Catherine departed from - it could have been the port of London near the Tower, but here's the biggest, seen from the blue arrow in the map above... the West India Dock, which we see in the painting below, published in 1862 by artist William Parrott:

There were a number of Passenger Acts passed in the 1800s both in Britain and the USA, intended to protect emigrants from exploitation by boat-owners and to set minimum standards. The downside of this, of course, was that it drove up the cost of the passage. For Catherine's voyage, the Passenger Act of 1849 applied. This document really is a very interesting insight into the age, and most excellently devised. Well done to those Victorian legislators. Here's an example; Catherine's £3 10s ticket, by law, had to include her food for the passage:

As we see above, in addition to her daily ration of 3.5 litres of drinking water, Catherine gets plenty of food - more than she's used to at home, no doubt - in fact more than she could possibly have eaten. Aside from baby, there were 6 persons in Catherine's party, which meant that they were entitled to 30lb of oatmeal an 12lb of rice a week!. And, interestingly, the rations are measured in their raw form - for example; flour. This is because - unless there are more than 100 passengers [for Catherine's voyage there are only 44] she'll probably have to cook the food herself:

Passengers were advised in traveller's guides to bring a few cooking pans and a few luxury food items if they could afford it, to supplement the plain fare supplied on ship.

In winter, the ship was required by the Act to carry 80 days' provisions for every passenger at the quantities prescribed above. In the summer, as was the case for Catherine, it was 70 days, so this was obviously the extreme maximum time the journey was expected to take, ten weeks, whereas a typical voyage time was six weeks. In some cases, depending on the ticket, passengers were allowed to keep any surplus when the journey was shorter, which could amount to quite a lot of food. How they would carry it must have been a problem. I suspect Catherine's economy passage would not have included this bonus.

In the 1840s the Illustrated London News were aware that their readers were curious about the conditions experienced by the hundreds of thousands of British subjects who were emigrating all over the world at that time. For their edition of 13 April 1844, they dispached an artist to draw a view of the accommodation, which is great for us, because we are also very curious to see what it looked like:

I think that's a pretty clear view of what it was like for our Catherine and her young family. That could be her in the image above, with her little baby, Jane, on her lap.

A very similar view is provided in the engraving of 1850 below, from an anonymous artist:

You got bare boards in your bunk and had to provide your own bedding. As for the living space offered, here are the specifications laid down by the 1849 Passenger Act:

I don't know about you, but I'm 6'1" and I like a nice big king-size bed. I might have a problem sleeping in an 18-inch-wide bunk.

Now that Catherine is safely on board, let's have another look at that passenger list:

Aside from Catherine's clutch of five, there are nineteen other kids on the voyage, of all ages, for them to play with during the six-week voyage. I think it's a fair bet that they are going to have a great time of it.

Catherine also has to adjust herself to life on board, and to her travelling companions. She was advised by the newspapers that the best strategy was to secure a berth as close to the fresh air as was available, and here I find Frederick Piercy's experience very useful in illustrating what it must have been like:

Frederick, as a Mormon, was a very God-fearing man, and several times in the book takes rather comical exception to the rough-and-ready sailors who swear profanities with every other word, and also shows us the bonds which must build between fellow-travellers:

The legislators knew the importance of keeping booze off the boat on a long voyage, as we see in clause 36 of the Passenger Act, below. A 20 quid fine would just about wipe out any profit for the Soldan:

![]()

After six weeks on the high seas, cooking and looking-after her five kids, Catherine's port of arrival hove into view: New Orleans. When we read the account of Frederick Hawkins Piercy - who travelled in 1853 on the same route on a ship laden with Mormon converts - we discover that the first counsel Catherine may have received upon approaching her New World was probably; "watch out for thieves":

As for Catherine's personal experience of the voyage, Terry Bigler provides us with a short but wonderful Cunningham family tradition - which has the absolute ring of truth about it - of Catherine's adventure, to fire our imagination:

'Catherine brought 5 children who had all been born in England. One child, Catherine, died earlier & was buried in England. An often told tale about their voyage was that a passenger had died onboard ship & his body was thrown overboard. A whale could be seen following the ship for sometime afterwards. The voyage lasted about 6 weeks.'

The death of the passenger was bad news for the ship-owners who were, by law, held responsible for the well-being of all on board. They could be fined for every person who died during the journey. And - by the way - the dead person's relatives were entitled to a full refund of his ticket! Fact!

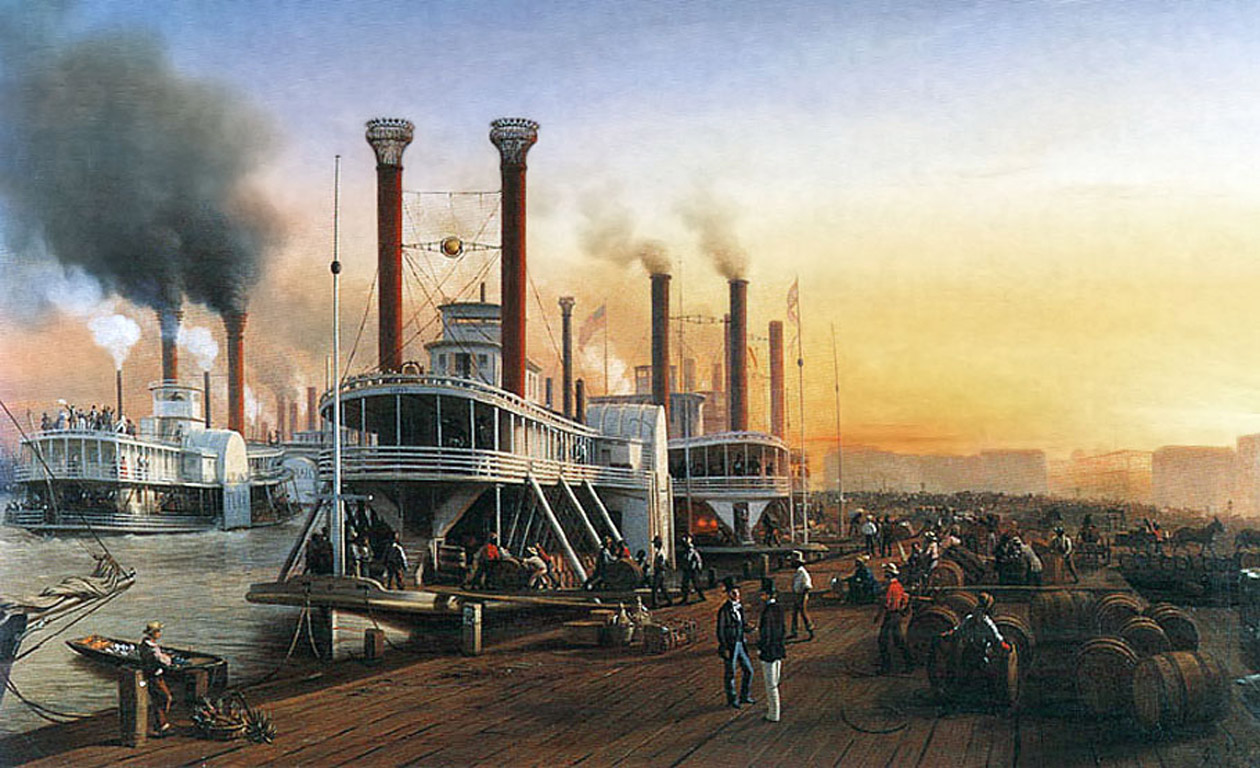

Catherine's destination is New Orleans, which, being the year 1850, is close enough for me to call the Wild West. Imagine the culture shock for Catherine. She has probably never even travelled from London to Brighton, and now she is arriving in the glory of the deep south, giant riverboats ploughing majestically through the waters of the Mississippi. New Orleans, seen below - obtained by America from France in 1803 as a part of the Louisiana Purchase - is already a large bustling city:

The beautiful picture we see above was drawn by artist J. Bachman in 1851. The seafaring sailing ships are at the right of the picture, and just a few hundred yards along the riverbank are the riverboats, some of which are setting off upstream along the Mississippi.

Catherine has no reason to hang about in New Orleans, which could be a den of iniquity, brothels, bars, gambling houses. She'll be on her way immediately, which we shall examine in a moment, but first, let's figure out where she's headed...

Catherine and her family had arrived in New Orleans on Saturday 23 March 1850. Just four months later, 22 July 1850, James and Catherine have been reunited and appear in their first United States census in Corydon, Harrison County, Indiana.

Circled in the map below, in the red circle, we see the location of Corydon, Indiana... It's a long, long way from New Orleans:

Now that we know Catherine's destination, let's review her journey. Upon arrival at the port of New Orleans from London, she'll say her farewells to the friends she made on the sea voyage, but Catherine's journey is not at an end...

It's only 100 yards in New Orleans from the ocean ship landing to the riverboat landing, but our Catherine has a huge journey, sailing up the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, ahead of her! I used that admirable resource, Google Maps, to calculate the distance along modern roads following the approximate course of the river, and it comes to 900 miles: but look at that that river - it ain't straight like a road. It's got to be at least 1200 miles, probably much more, maybe even double.

And Catherine's on a Mississippi paddle steamer for goodness sake! The painting we see below, of New Orleans in 1853, by French artist Hippolyte Sebron, is titled Bateaux á Vapeur Geant [Giant Steamships]:

And if we want to envisage the Mississippi River, we have the perfect example - Mark Twain who grew up on the Ol' Man River and who set his adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn in exactly this time and place; the 1850s:

Catherine's riverboat journey must have taken quite a while, and she probably had to change boats several times. and may have stopped off at towns on the way.

But let's say a speed of 10 knots, 12 hours a day. By my reckoning, to cover 1200 miles, that's an absolute minimum of 10 days - perhaps less if they could navigate efficiently by night. And it's yet another cost for the family to fork out for, so let's have a close look at a steamboat in a great photo of c1856:

Let's hear what our Mormon author Frederick Hawkins Piercy has to say about the riverboats in 1853, but before we do, I must caution you that I have included his words in this passage in the interests of historical accuracy as an illustration of the culture which prevailed in the USA at this time:

I must add that, later in the book, Frederick shows himself to be more liberal and defends black people against slanders even worse that the one in that paragraph.

Let's move on. We need to know what kind of accommodation Catherine will experience for her journey up the Mississip'... but she won't be travelling first class, she'll be among the 'ordinary passengers' lying on the boards of the deck:

The Cunninghams were not alone in the exodus to the USA. British newspapers in the 1850s were full of advice to would-be emigrants.

That Catherine and her family had to spend their nights, many nights, travelling up the Mississippi sleeping on the open deck of a paddle steamer is confirmed by the Morning Post of Wednesday 24 September 1851, giving caution to readers who were contemplating emigration:

So it is likely that Catherine and the kids made their beds on the open-air flat deck, which I would say is preferable to shoehorning oneself into an 18" berth as they had on the sea voyage, except for the additional nuisance of mosquitoes. What they did when it rained is not recorded. Presumably there was some cover.

The steam engines on the riverboats were fuelled by wood, and they had to stop to stock-up. This involved hard work for the all deckhands, whom Frederick Piercy describes...

Below we see the steamboat Grand Turk stocking up its 'Wood Pile' on a remote stretch of the Mississippi, a similar scene which Catherine and her kids must have witnessed, no doubt gawping in amazement at it all, and at the vastness of the territory:

And there it was. After such a long and arduous journey, Catherine and her kids must have been heartily glad to reach their final destination, however humble it may have been. A rural homestead just outside Corydon, Indiana.

Corydon, though small, was the former State Capital of Indiana (1816-1825), and the Cunningham family tradition suggests that James and Catherine settled there because other members of the Cunningham family had already emigrated and were living nearby. In 1848-1850, James was working at White Cloud, a few miles west of Corydon; this had been on a farm - but we can see that in the 1850 census below, he is again practising his trade as a shoemaker.

There's a lot of information on this census. The Cunningham children, in common with nearly all the other children on the sheet, are not attending a formal school. James and Catherine, who have spent every last nickel on their emigration, naturally have no value of real estate.

Having settled in Indiana, family life resumes, and, on 18 April 1851, Catherine's first American baby is born, and is given a suitably American name: Henry Columbus Cunningham. This chap is the ancestor of our correspondent, Terry Bigler, who lives in Corydon!

Here's a surviving photo of Henry Columbus Cunningham, perhaps in his twenties, courtesy of Terry Bigler:

On 13 July 1854, Catherine gave birth to her fifth daughter, Caroline 'Carrie' Cunningham in Corydon, and soon after this, her sixth daughter and final child, Sarah 'Sallie' A Cunningham.

On 04 April 1859, shoemaker James Cunningham Sr took the oath to become a naturalised American.

The next we see of the family is the US census of 21 June 1860. They are in Harrison Township, the small regional subdivision which includes Corydon. Of interest on the census is the description "Free Inhabitants...", a reminder that that this is still the era of slavery. The 'Colour' [of skin] column is not filled-in on this sheet, but if you look back at the 1850 census, some of the Cunninghams' neighbours had been free blacks.

Catherine and James were clearly living in an area occupied by farmsteads; all of their neighbours were farmers. James was continuing his living as a shoemaker, and in the interesting (and intrusive!) feature of early American censuses, we can see that the family appears still to be hard-up for cash: ten years in the USA and they still haven't a nickel to their name.

Living next door is the Cline Family, and amazingly, courtesy of Terry Bigler, we have a late surviving photograph of the Cline residence, which gives us a clear idea what Catherine's house must have looked like - though perhaps rather smaller:

The mother of the the Cline family in above house was Catherine's next-door-neighbour in 1860, Elmanda Cline. Elmanda was only 31 in the 1860 census, but here's a photo of her in her old age... Victorians never smile for photographs:

Three months after the census, on 13 September 1860, Martha Cunningham, aged 17, - whom we saw earlier being born in Southwark - was married to Francis Cline, aged 25, who was the younger brother of Elmanda Cline. Tragically Martha died in 1865 aged just 22. Seven years after Martha's death, Francis Cline went on to marry Martha's younger sister Caroline Cunningham, who was only 6 years old in the above 1860 census!

And Harriet Cline, who was aged 7 in the above census sheet, and living in the very house we see above - the 'girl next door' - is destined to marry Henry Columbus Cunningham, whose photo we saw earlier, who can be found aged 8 on the same sheet. (both are ancestors of our correspondent Terry Bigler).

Of course we'd like to locate the house where Catherine lived. According to Terry Bigler, the Cline house, and consequently the Cunningham house, was near 'Dixie'. In the map below, I have circled the Dixie Road in red, about 6 or 7 miles south-west of Corydon. It's as close as I can get:

Nine months after the census is the Presidential Election of 1861; Catherine Partleton and her family are now living in a United States whose president is Abraham Lincoln:

The policy of Abe's Republican Party was to suppress any expansion of slavery and of course what ensued was the American Civil War which commenced on 12 April 1861.

Corydon has a place of fame in the history in the Civil War... the story of Morgan's Raiders - which is wonderful for us because it provides yet another twist in Catherine's amazing story as she was caught up in it.

Morgan's Raid was a highly publicized incursion by Confederate cavalry into the Northern states of Indiana and Ohio. The raid took place from 11 June 1863 to 26 July 1863, and is named after the commander of the Confederates, Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan, the gentleman with the faintly insolent aspect in his gaze whom we see below:

xxxx

xxxx

On 08 July, Morgan crossed the Ohio River at Mauckport, Indiana, despite orders

to remain south of the river in Kentucky. Union military officials called out

the militia in Indiana and Ohio and worked feverishly to organize a defence.

At 11:00 a.m. on 09 June 1863, the Confederates reached the outskirts of Corydon. Blocking their way a mile south of town was a line of hasty works manned by the Sixth Indiana Legion under Col. Lewis Jordan. There was no question that Morganís guns could have made short work of these 400 farmers-turned-soldiers. Using an artillery section and one battalion to pin the defenders, Col. Richard Morgan, the general's brother, launched a flank attack that quickly routed the defenders. After a short but spirited battle of less than an hour, Jordan retired with his militia into Corydon, but soon surrendered when Rebel artillery fired a pair of shells into the town.

Gleeful Confederates then spent the afternoon plundering stores and collecting ransom money. Morgan threatened to torch three local mills, and demanded amounts ranging from $700 to $1,000 from each to save them from destruction. The county treasurer paid Morgan $690, and two leading stores $600 each. Later that day, the raiders left Corydon and continued their northward ride, scouring the countryside to collect fresh horses and additional booty, illustrated by this re-enactment held in Corydon:

And here's where Terry Bigler's Cunningham family history comes in again. Catherine certainly doesn't have $1000 to give to Morgan's Raiders - or even a horse, probably. But she was definitely paid a visit, recorded in the family history, just as she was laying out the dinner for the family. Morgan's Raiders helped themselves to the dinner - thank you ma'am - and then went on their way!

Left (re-enactment): Could be Catherine with her daughter Sallie Ann in 1863!

Left (re-enactment): Could be Catherine with her daughter Sallie Ann in 1863!

Whew!

The Civil War ended in 1865, and we move on to the US census of 1870... note that since the abolition of slavery, the census no longer has to specify 'Free' Inhabitants. How are James and Catherine getting on?

Above we see that they finally have some modest assets to their name. At home are Henry and Carrie, and it is noteworthy that they have both attended school within the year at such advanced ages. They wouldn't have got that as working-class kids in Victorian England where their education would have ended at 14 or earlier. Also we see see something new. Catherine shows her caring side as we observe that she is looking after an orphan, 'Henry Reylonds' [Reynolds? Reiylola?] who is - in an unsympathetic Victorian way - recorded as 'Idiotic'.

James and Catherine's son David Cunningham, who married Sarah A Conrad in 1866, lives next door, and Catherine has two little grandchildren, Albert and Charles. Also in this household is another orphan named 'Reylonds', clearly the brother of Henry Reylonds. I believe I have deciphered the words next to 'orphan' as 'sup[porte]d by C J'. I presume C J means the county or community. Catherine may be getting some income for looking after young Henry Reylonds.

And this brings us nicely to a treat: a photograph, taken in the 1880s. Catherine's son (and next-door neighbour) David Cunningham, who had been born in London in 1845, his wife Sarah Conrad, and Catherine's grandchildren, Albert and Charles:

I'm guessing, but I believe that must be Sarah Conrad's mum and dad in front. This photograph was posted online by Terry Bigler, descendant of Catherine. Thanks for that, Terry!

Catherine lived out in the countryside: Corydon was 6 or 7 miles away - 2 hours walk - so she probably didn't go into town very often. But when she did, we can see what Corydon looked like to Catherine and James.

But before we do that, here's a surprise: We have photographs of James Cunningham (1808-1893) and Catherine Partleton (1810-1895) late in their lives:

xxxx

xxxx

Catherine was born in 1810. By my reckoning, she's in her seventies in the photo above, which means the pictures were taken in the 1880s.

Below is Corydon in 1896:

The Partleton Tree was fortunate enough to be contacted by historian Bill Doolittle of Corydon who has put us straight regarding what we see in the photos. And I've located a lovely little street map of Corydon of 1872. Perfect. I shall marry Bill's quotes to the map and we can really tell what we're looking at.

The first picture - the one above - is 'Mulberry St, looking south toward the South Hill. Probably shot from a window of the Corydon School on Mulberry, which is up Cedar Hill north of downtown. The house in right foreground is the Federal-style brick home c. 1821 of Henry M. Heth, of the prominent Heth family of Harrison County pioneers. Harvey Heth (uncle, I think) laid out the town of Corydon in 1808. On the left is the old Corydon Christian Church.'

The viewpoint is from the blue arrow in the map below:

The next photo is Chestnut Street, 1903; 'on Chestnut Street SW corner intersection with Mulberry.'

Our point of view is from the red arrow in the map above.

The next photo of Corydon was taken in 1895 - the year Catherine died - an affluent-looking street:

As for the photograph above, according to Bill; 'The businesses are on Elm Street, one block west, on The Square, adjacent to the Old Capitol.' Tiny Elm Street is circled green in the map below:

Below is a building which would have been very familiar to Catherine. Step into her shoes (which were, of course, made by her husband!) as she takes a stroll through Corydon, past the former State Capitol:

The State Capitol had been built in 1816. Here's how it looks now:

One can tell from the position of the chimneys that the older photo of the Capitol was taken from the viewpoint of the yellow arrow in the map. The modern picture was taken from the opposite corner where there is another chimney preserving the symmetry of the building.

The next photograph is of the bridge over Big Indian Creek, on western side of Corydon, looking out to the countryside. If someone could tell me which road on the map leads to the bridge, that would be much appreciated.

In August 2011, Partleton Tree correspondent Scott Ginkins provided us with the answer to that puzzle:

Thanks for that, Scott! The photo of the bridge was taken in Walnut Street from the viewpoint of the purple arrow in the map below:

In the 1880 census, we find that James and Catherine in their old age have crossed the state line to Calhoun, McLean County, Kentucky, where they are staying with their son James, a grocer, and his wife Bridget Wall.

You may remember James being christened in Trafalgar Square, a long, long time ago! And finally we discover that Catherine preferred to be called Kate:

Below we see Calhoun, about 80 miles across the Ohio River from Corydon:

Note also Corydon's proximity - across the state line on the Ohio River - to Louisville Kentucky. In Catherine's time - 1875 - the first Kentucky Derby was held at Louisville in front of 10,000 spectators, a tradition which continues to this day. Also close to Corydon is Fort Knox, which was an actual fort named Fort Duffield in the 1800s before being renamed Fort Knox and becoming the US Gold Bullion Depository in 1937...

Sadly, almost the entire 1890 US census was destroyed in a fire in 1921, so we get no view of Catherine and James. However, we do know that they did not remain in Kentucky, but returned to Corydon.

We are nearing the end of Catherine and James' epic journey, & it's such a long story, I thought it would be a good moment to recap: Swallow Street Westminster to Dixie, Corydon, rural Indiana. We can surely imagine Kate regaling her grandchildren with tales of her appearances on the London stage, the ocean voyage, the whale, Morgan's Raiders....

James Cunningham died on 8 August 1892 at White Cloud, Indiana.

Catherine Partleton lived a further 3 years, finally passing away on 28 September 1895...

But her story is not quite complete yet, because uniquely - so far - for a 19th century London Partleton, Catherine's passing is marked by a memorial. The picture below of the beautiful Heidelberg United Methodist Church Cemetery, Corydon, was taken by an anonymous photographer who unknowingly captured a picture of Catherine's gravestone:

I've got to comment that it's truly a stunning location. And a severe contrast with old graveyards in Britain which are usually neglected.

Frustratingly, I've not been able to glean from those censuses exactly where Catherine and James lived [can anyone help with that?] But the location of the graveyard may give us a clue. It's a mile or two south-west of the town, in the blue circle below:

Our correspondent, Terry Bigler, whose mother's surname was Cunningham and who is descended from Catherine and James, visited the site and took this picture of James and Catherine's shared headstone:

So ends the story of Catherine Partleton 1810-1895.

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... or would you like to discuss any of the history... or if you have any observations or comments... all information is always welcome so why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'Showbiz Partletons' Theatre Page