Catherine Partleton (1810-1895) in 1826

Part I

When you are researching family history, some people just go missing. Catherine is one of these. She was lost... and then she was found.

Catherine Partleton was born on 18 October 1810 and christened on 02 December 1810 at the church of St James, Westminster, London, the daughter of house painter Benjamin Partleton (1774-c1833) and his wife Catherine Iremonger.

Here's where Catherine lived from 1810 to 1815; circled in yellow in the map below - Swallow Street, Piccadilly, in the Parish of St James:

In the map of the Parish of St James below, we see the exact location of the house where Catherine was born, 43 Swallow Street, at the corner of Beak Street, circled in red:

Below we see a Victorian view of St James church seen from the viewpoint of the blue arrow in the map above. It was painted looking south from Swallow Street by artist Robert Dudley. At the time Mr Dudley sat here with his paintbrushes, Catherine was long gone from Swallow Street and had moved south of the river Thames to Southwark:

But step inside the church for her christening in October 1810, if you like, because we have a picture of interior of St James Piccadilly, just as it looked on that day:

If you'd like to see the font in which she was baptised, take a visit to the church because the original is still in there.

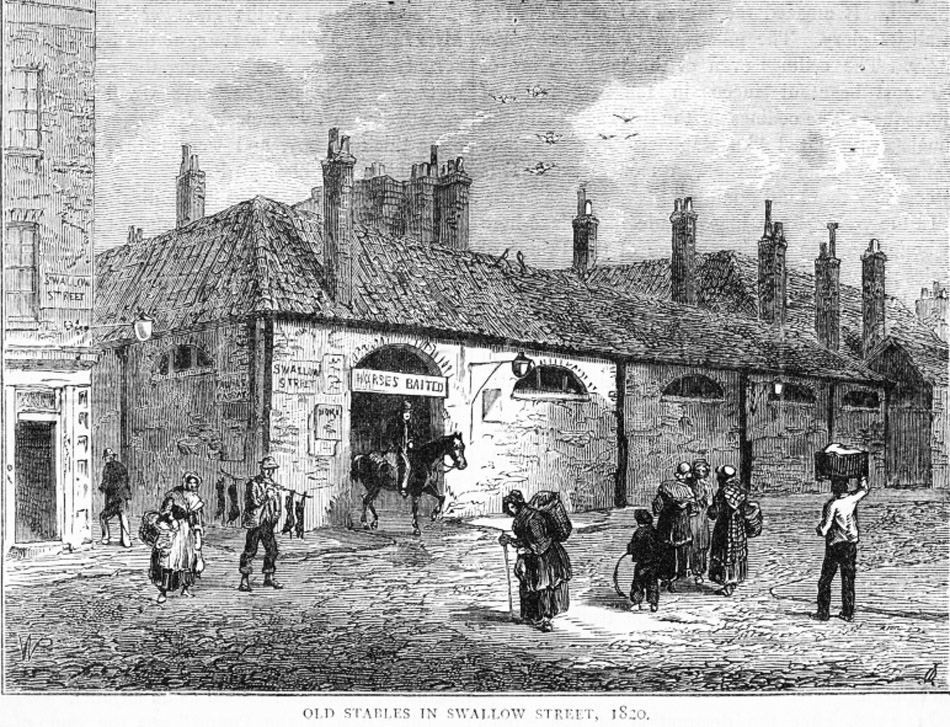

Below is a view of Swallow Street, drawn just five years after Catherine's family had moved out. Captured in this picture, for all time, is Major Foubert's Riding Academy, which had been established in the 1690s. In the street outside - which is a busy and chaotic thoroughfare connecting Piccadilly and Oxford Street - we see rabbits and bread for sale:

The engraving above is the junction of Swallow Street with Major Foubert's Passage, seen from the viewpoint of the green arrow in the map below. The outline of the stables is visible in the map, at the corner of the street:

In January 1815, Catherine's family had to leave. They had been living at 43 Swallow Street for decades, but their long - and cheap - lease expired in 1815. The house on Swallow Street was going to be demolished as a part of the massive development to create the brand new Regent Street, and there's nothing they could do about it.

Catherine was just 4 years old when they moved, so she might not remember much of Swallow Street, but let's remind ourselves where we are; in the yellow circle in the map below:

Between 1815 and 1822 the family moved south of the river to the poorer district of Lambeth, circled red in the map above.

But this is not the end of the family's connection with the north side of the Thames. Catherine's parents put their children on the stage. On Thursday 02 November 1826, at age 16, we find Catherine Partleton on the bill at the Adelphi Theatre on The Strand.

Partleton, Miss

Caliph's guards, Cadi's black slaves, peasants, soldiers, imams (18 appearances) in The Barber and his Brothers (2 Nov 1826 - 22 Nov 1826); huntsmen, peasants (21 appearances) in To Fry Shots (16 Nov 1826 - 9 Dec 1826)

Let's locate The Strand on our map of London - it's circled green below:

And we can pinpoint the exact location of the Adelphi Theatre:

Now we can really step into their shoes. Let's put ourselves in the place of Catherine's parents Benjamin and Catherine and imagine the night of Thursday 02 November 1826.

Young Catherine's going to appear in a musical comedy at the Adelphi Theatre, possibly her first appearance, and we're going to watch.

The actors' entrance to the theatre is surely at the back, but below is a nice atmospheric print of punters queuing for the Adelphi at the time of Catherine's appearances:

Below we see the first of Catherine's shows, The Barber and His Brothers, highlighted in purple in The Times newspaper in November 1826:

So, let's slip on Catherine's shoes and step nervously on to the stage...

Below we see the interior of the Adelphi Theatre, in a picture by artist G. Jones held at the London Metropolitan Archive. Though this engraving was published in 1816, the theatre is exactly as Catherine would have seen it in 1826:

Not all actors like reading reviews, but if Catherine did, she would have been quite happy with the one we see below, by a Morning Post journalist who watched The Barber and His Brothers, including the performance of our Catherine, on its opening night:

Left: The Morning Post, Friday 03 November 1826

That review was published on Friday 03 November 1826. The Adelphi Theatre was a regular advertiser in The Morning Post, so I'll leave it to the gentle reader to decide if reviewer's upbeat opinion was affected by the need to keep its patronage.

Thanks to this newspaper cutting, we can tell that Catherine's role involved singing and dancing.

If you were paying attention, you may have noticed from that picture of its interior that the Adelphi was also called the Sans Pareil, which had been its name until 1819.

The object we see above is a subscription token for the Adelphi, a season ticket if you will. It's made of ivory. Mr Thomas must have been an avid attendee in the 1810s.

We'd love to have a look at young Catherine, and sadly that ain't gonna be possible, but let's have another look at that advert:

We don't have a picture of Catherine at this age but we can get a good look at some of the actors with whom she worked on that night. Circled in red in the advert is John Reeve (1799-1838), who played the leading man:

xxxxxxx

xxxxxxx

Also on the bill for The Barber and His Brothers on 03 November 1826 was actor Benjamin Wrench (1778-1843), drawn below by portrait artist Thomas Charles Wageman:

And here's Frederick Yates (1795-1842), depicted by artist William Say in 1826 - the same year he and Catherine appeared on the same stage at the Adelphi:

Catherine was only in the supporting cast, but she must have known all three of the leading gentlemen we see above fairly well, especially Frederick Yates, who was the manager of the Adelphi.

By the end of November, Catherine was appearing in another singing-and-dancing comedy show at the Adelphi, carrying the odd name To Fry Shots:

The leading man in this production was again John Reeve, as we learn from the review published in The Morning Post on Friday 17 November 1826:

Left: The Morning Post, Friday 17 November 1826

This piece explains that To Fry Shots was a parody of a serious German opera Der Freischutz [the Marksman] and if we look back at the advert from the beginning of November, circled in green below, we see that Der Freischutz had been showing at the rival Theatre Royal Drury Lane in November 1826, which is probably why the Adelphi chose to run their spoof at his time:

So, Catherine Partleton was singing and dancing on the London stage in the 1820s, and we know that some of her brothers - the younger ones - were doing the same. Where did they get that from? That's not obvious: Catherine's dad was a general carpenter / house painter, and her mum Catherine Iremonger was a country-girl from the village of Isleworth. Where did the singing and dancing come from? Perhaps more research will reveal all.

Catherine's career on the stage probably carried on after she was 16 but I have limited information which relates only to her performances in 1826 / 1827, which can be found here: http://www.umass.edu/AdelphiTheatreCalendar/m26d.htm

Six years later, in 1832, aged 22, Catherine was still living in Lambeth. Moving to Lambeth his has been distinctly a move down the scale; the living conditions are overcrowded and unsanitary; it is a place for London's poor. We know she is there because she is married to James Cunningham, a shoemaker, at the church of St Mary-at-Lambeth. The date is Saturday 26 May 1832:

The certificate is witnessed a little shakily by Catherine's dad Benjamin (he died the following year), and by James Cunningham's sister Martha.

By 1835 Catherine was still living in Lambeth and gave birth to her first child, James. For James' christening, she and her husband made a journey north of the river to the parish of St-Martin-in-the-Fields.

Why did they do that? Well, at this time it was the parish of her husband's family, the Cunninghams. Baby James was christened on Sunday 16 August 1835 at the grand and famous church of St Martin-in-the-Fields in Trafalgar Square. Below we see it at the left hand side of this beautiful engraving of 1842:

Trafalgar Square is out of picture at the left, but Catherine couldn't stop to admire Nelson's Column on the day of her son's baptism in 1835 - the construction of this famous monument on the doorstep of the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields didn't start till 1840 and finished in 1843.

Thomas Shotter Boys created the above elegant watercolour in 1842, but carefully kept the construction works around Nelson's Column - which were in full swing at this time - out of the picture. The reason for this is obvious in the fascinating - very early - photograph below, taken in two years after Shotter Boys' painting, in April 1844, by pioneering photographer William Henry Fox Talbot... temporary fences still in place around the completed monument, splattered with advertising bills, and scaffolding cluttering the base of the monument, would not have made for a very attractive painting:

The one poster which is readable advertises Polkamania, reflecting the new polka dance craze which was sweeping across Paris and London in the 1840s.

Left: Punch Magazine, July 1845

Left: Punch Magazine, July 1845

Since we know Catherine had been a professional dancer, she could hardly have been unaware of this trend.

Let's have another look at that watercolour:

What are the two fellows pulling across the road in the foreground?. It's a water cart. They are spraying the road to keep the dust down in the summer.

Our viewpoint looks straight down The Strand from the the red arrow in the map below; St Martin-in-the-Fields church is circled in red, and - incidentally - the Adelphi Theatre is somewhere in distance along The Strand:

Why is the church called St Martin-in-the-Fields?

Well, it's not St Martin who's in the fields. It's the church which is in the fields.

In earlier times it had lain between the two separate cities of Westminster and the City of London - as we can see - St Martin's church is circled red, north of The Strand, in this beautiful 1560 map of London:

The earliest record of a church on this site is in the year 1222.

The church which we see in the map above is one which was rebuilt by Henry VIII in 1542. It survived the Great Fire of London in 1666, but was rebuilt again in 1721 which is a pity... Henry's Tudor-style church would be a really striking feature of Trafalgar Square.

Here's the parish register of St Martin-in-the-Fields showing the baptism of little baby James Cunningham in 1835:

Below we see the interior of the church in c1840, drawn by artist H Buckler.

Catherine and James Cunningham, and some members of their extended families gathered here to celebrate the new baby:

Here's the interior of St-Martin-in-the-Fields as it appears now; unchanged since 1721, and exactly as Catherine saw it in 1835, as she held her first baby in her arms:

The baptism of a working-class baby in this grand church is rather startling at first sight for the family history researcher.

Were the Cunninghams rich? But the answer is that they were emphatically not. Yes, the family live in the parish of St Martin-in-the-Fields, but at that time central London encompassed plenty of poor dwellings as well as wealthy ones. Catherine's husband James is, we see on the Parish Register, a cordwainer - a shoemaker: a notoriously poorly-paid trade, and one which was commonly taught to destitute youngsters in workhouses.

In fact the address given on the Parish Register of Baptisms - White Hart Street - is not in Westminster but in Lambeth. In the map below, the location of White Hart Street is circled in purple:

The Victorians and Georgians were absolutely hopeless at naming streets. There were two White Hart Streets in the borough of Lambeth, no more than half a mile apart, and for a long time I was looking at the wrong one, but now we know for sure. She's in the area circled in purple, which at the time was known as Newington. Today we call it Elephant & Castle.

In the 1830 map below, we see the exact location of Catherine's White Hart Street:

In the painting below, of 1825, from the blue arrow in the map above, we see the Elephant & Castle pub directly ahead exactly as Catherine would have seen it. Her residence is along the street branching to the left directly ahead.

White Hart Street is frustratingly obscured by the Newington Turnpike House at the left of the picture.

Immediately behind the trees on the right in the picture above is another building which Catherine would have seen, even if she didn't know what it was. These are the Fishmongers' Almshouses, painted by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd, from the viewpoint of the yellow arrow in the map. The year looks like 1842 on the inscription. There are two large buildings. The one we see below is the older, northernmost one which was built in 1621, demolished in May 1851:

These buildings were erected by the Worshipful Company of Fishmongers to care for [some of!] the poor people in the area... "What is the Worshipful Company of Fishmongers?", I hear you ask, and its a good question. It was a city Guild. "What is a Guild?" I hear you ask, and it's a good question. Guilds are sometimes cited as early trades unions, but they were not really. They were closer to associations of businessmen. They established and maintained monopolies on their trade and prices, excluding outsiders from competing.

Guilds were already on their way out in Catherine's day, and were pretty much broken by free trade in the 1800s. You'll find very little reference to anything piscene or aquatic in the minutes of the Fishmongers Company at that time. They were much more concerned with managing the Company's extensive, delectable, and profitable properties in London. The Fishmongers' Company still exists, and still owns those properties today. They run charities, but if you can figure out what they really do these days, you're a better man than I. The Fishmongers' Almshouses at the Elephant & Castle were demolished in the 1850s, as we shall see in a moment.

Let's get back to Catherine. From the map of 1803 below, we see that White Hart Street had at that time been just a small row of ten houses called White Hart Cottages:

And below, in John Rocque's beautiful map of London of 1740, we see the pretty, unspoiled village of Newington in the countryside a hundred years before Catherine lived there. And we discover how White Hart Street got its name; from the White Hart Inn which faced out to Newington Village Green:

Three years after the birth of their first child, Catherine and James have their second; Hannah:

Catherine and James are not going north of the Thames for the christening - this time they're going to their local church, St Mary Newington:

The above view of the church is seen from the viewpoint of the green arrow in the map below:

Let's have another look at that Parish Register with little Hannah's birth record:

In 1835 Catherine had been living in White Hart Street. Now the family have apparently moved to Baker Street... but if we inspect the map below, we find that... well... actually they haven't moved an inch. Between 1835 and 1838, White Hart Street has been renamed. Why? Well, there you have me. Baker Street is an even worse name that White Hart Street. There are dozens of Baker Streets in London.

Baker Street is circled purple below:

This map was printed in the 1860s. At this date Catherine is long gone from Baker Street - and we see the brand-new Elephant & Castle railway station (1863) slap-bang on top of Catherine's former residence - so much so that the mapmaker has to snake the words Baker Street around this huge new obstacle.

Catherine never saw the new railway nor did she witness the demotion of the Fishmongers Almshouses at the point of the yellow arrow. The southern almshouses were replaced, as we can see at the point of the yellow arrow on the map, by the gigantic Metropolitan Tabernacle in 1861:

I used to drive past this vast edifice every day and wonder vaguely what on earth it was:

Well, it looks like one would go there to worship Zeus, but that would be sacrilegious. Actually It's not a Greek temple but a church. A very big Baptist church. If it looks different in the modern photo, that's because everything except for the portico burned down in 1898 when it was only 37 years old. I suppose God has his reasons. Oh, and it was destroyed again by bombing in 1941. And rebuilt.

One last picture of the area, and then we'll move on with Catherine's life:

Ok, the above photo was taken in 1930, but we can see many of the buildings which had already been built slap-bang on the old village green before Catherine's lived at this very spot in 1835. All of this was knocked down in 1959. We're standing on Walworth Road [Cumberland Row] at its junction with Baker Street, looking north towards the Victorian rebuild of the Elephant & Castle pub, from the viewpoint of the red arrow in the map below:

Catherine's about to move home, so let's take one last look at the little village of Newington as it became subsumed into the vastness of London between 1740 and 1863. If you are like me, then you'll love to compare maps...

Below: 1740 and 1803

Above: 1830 and 1863

We move on to 1840, and the family have moved a little, to Southwark. They've relocated from the purple circle to the dark blue circle in the map below:

This is where Catherine's third child, Catherine, was born in 1841. The birth was in the parish of St George the Martyr on Borough High Street, Southwark, circled pale blue in the map above; the church seen below in a painting of c1830:

The artist's viewpoint for this painting is from the pale blue arrow in the map below:

As you can see from the map, Borough High Street is the main route south from London Bridge. Since London Bridge was the only bridge in London over the Thames from Roman times until 1750, we can appreciate that Borough High Street is quite ancient. Catherine would be very familiar with it, so let's have a look at a nice picture of it, engraved in 1830:

I can't nail down our viewpoint, but from the curve of the road, and from the shadows [the sun never shines from north], we are probably looking at the east side of the road. I don't know what the building works are in the foreground; that's a bit frustrating. Can anyone help? What's that tall building at the left?. But never mind all that - look at the lovely picture!

The next photo shows surviving buildings on Borough High Street in the 1890s. These include the homes of Frederick Redman, butcher at No 146; the family of Walter Dick, shoemaker at No 152; and Samuel Ford Chaplin, rubber dealer at No 150. And is that really the Boys Toilet Club at No 148? Well, yes it is. A Toilet Club is Victorian parlance for a fancy hairdresser where one could be pampered; shampoo, haircut and a shave! Strange but true.

The above photo was taken from the viewpoint of the yellow arrow in the map below:

And, since the street numbering is still the same as it was in late Victorian times, from the viewpoint of the purple arrow, we can have a look at 150 Borough High Street today. It's clearly visible in the image, courtesy of Google Street View:

Oh dear. All things must change. Or not. If they existed today, those old buildings would be protected. But it's too late, they're gone, gone. All that remains in this view is the church of St George the Martyr.

Below we have a nice aerial view [c1920?] which can be matched to the map above. The spire of St George the Martyr is just peeking out at the bottom (blue). In the distance, by London Bridge, we see St Saviour's church aka Southwark Cathedral (red). A little to the east, near the river, we see the bell tower of St Olave's church (green) which was demolished in the 1920s.

Finally, one last look at Borough High Street. In 3-D, in Victorian times. From the viewpoint of the red arrow in the map. Cool. Nothing else quite puts you in their shoes as well as this:

The trick with the stereoscopic picture above is to sit about a foot from the screen, cross your eyes and relax. The two images will resolve into a single 3-D image. The above picture of Borough High Street is a very nice one, highly three-dimensional, so try it - it really puts you in the place - just look at the young lad sitting on the cart.

Let's move our map a little south. Now we see the location of St George the Martyr top right, and the locality of an area known as St George's Circus:

As previously mentioned, in April 1841, Catherine gives birth to her third child, Catherine Cunningham, named after her mother Catherine Partleton and grandmother Catherine Iremonger.

And three months later, we discover exactly where they are living - Little Surrey Street, Southwark - because we find them in the census held in July 1841. We see Little Surrey Street circled in yellow in the map above, with James and Catherine's census record below. We also discover that James Cunningham's mum and dad, shoemaker David Cunningham and his wife Elizabeth Lysons are living with some of James' brothers and sisters at Gloucester Street, circled in orange, just around the corner in the parish of St Mary:

Blackfriars Road, the main thoroughfare heading north, was previously called Great Surrey Street, hence Little Surrey Street for this branching side-road. It sounds quaint enough, but close examination shows that James and Catherine and their three children are living in a single room in conditions of the most extreme poverty:

The above is Charles Booth's Poverty Map. Catherine is in the yellow circle. This is a rare occasion where see a Partleton living in a street coloured black on this map, categorised as 'Vicious, semi-criminal'.

And here is Charles Booth's own personal account of his walk down Little Surrey Street in later Victorian times:

'Very poor: nearly every door open: heavy bloated-faced women: middle-aged & old not young mothers: bird cages at windows: houses in fair outward repair: fearful mess of bread, meat, paper & sacking in the street: same class as Joiner Street: gas lamps from wall brackets: children sore-eyed, hatless, some clean: many cats: organ playing but only one child dancing.'

Further evidence that Little Surrey Street is a bit rough comes from an article in The Times from a few years before Catherine lived there:

We'd have to be very lucky to get a picture of Little Surrey Street, but do have a photo of its near-neighbour Matain Street, or Miniver Street as it was known in 1938 when this picture was taken:

If you want to locate Matain Street, it's circled in purple in the poverty map above.

Let's bring back our useful general area map:

Again we can step into Catherine's shoes, probably made for her by her husband the shoemaker. It is the year 1834, and she walks past the obelisk monument in St George's Circus, seen in the watercolour below. If you look at the map above, our viewpoint is from the blue arrow.

Artist Thomas Hollis (1818-1843) set up his easel, and Catherine's street was just 20 yards behind his back.

In the distance, along Lambeth Road to the left, we see the impressive frontage of the famous Bedlam Lunatic Asylum:

If we fast-forward 175 years in the future, we can see how the obelisk looks today. It was installed in 1771, relocated to a park in 1903, and reinstated in its original place in the 1990s:

The road branching to the right is London Road; the Georgian buildings (c1810) were there when Catherine lived in the vicinity; she'd have walked past them many times. In the present day, Little Surrey Street has been redeveloped, but one or two Georgian buildings survive in the surrounding streets.

In our modern photo, Hoodies are passing a pleasant day skateboarding on on the traffic island and sitting on the base of the Obelisk. Aw, don't you just love 'em? But it's not a new phenomenon as we shall see.

The Obelisk was erected to celebrate the completion of the new roads at this junction in 1771. The Lord Mayor of London, who went by the surprising name of Brass Crosby, was so excited that he agreed to having the obelisk erected as a memorial. It's engraved with 'useful' information such as that it is 1 mile 301 feet from Fleet Street:

Blackfriars Road, leading north from St George's Circus, is home to an institution, Magdalen Hospital, at the point of the red arrow in the map below, just a few yards from Catherine's home:

Magdalen Hospital was a refuge for prostitutes, which we find described in Mogg's New Picture of London and Visitor's Guide to its Sights, published in 1844:

Here's a picture of the building:

The whole area is filled with charitable institutions. The next engraving is the Asylum for the Indigent Blind. Indigent means lacking the essentials of life such as food and clothes.

The above picture is from the viewpoint of the purple arrow in the map below:

Nothing in London ever stays the same. Though we can see from the inscription on its frontage that the Asylum for the Indigent Blind was built in 1814, it was knocked down in 1901 to create a night storage depot for Underground trains on the Bakerloo line.

Here's another view of the obelisk, with a 19th-century hoodie leaning back against the railings. This time we're looking directly north, up Blackfriars Road - where we see the Surrey Toll Gate. Toll gates were everywhere in London during this era, like a spider's web. You couldn't avoid them if you were entering or leaving the city. It was how they paid for the upkeep of the roads. Catherine and James didn't have to pay - as they most assuredly didn't have a carriage.

Directly behind the toll gate on Blackfriars Road is another local landmark: the Surrey Theatre, seen more clearly in the 1828 engraving below.

This is only 150 yards from James and Catherine's residence. It's hard to imagine that they didn't visit it, especially given Catherine's acting background, assuming they had a few shillings to spare. It is entirely possible that Catherine has performed here; she and her brothers appeared in minor roles in many well-known London theatres:

This engraving of the Surrey Theatre is seen from the viewpoint of the tiny orange arrow in the map below:

In 1865 the theatre burned down during a performance, as we see in the dramatic engraving below; dancers escaping through the rear of the building:

But we seem to have wandered from the track, which is the story of Catherine Partleton and James Cunningham. They certainly didn't witness the 1865 theatre fire: they were long gone...

We left them in 1841, at the census, with children James (1835), Hannah (1838), and Catherine (1841).

On 24 April 1843, Catherine gave birth to her third daughter, Martha, named after James' sister Martha who had witnessed the marriage.

In 1845, James and Catherine are struck a terrible blow with the death of little Catherine, aged just 4, in the January quarter. This identification is yet to be confirmed for definite by a death certificate. Soon after this, in the same year, 23 June 1845, a second son is born, named David after his granddad, and we see the baptism of David and his older sister Martha on 03 August:

From this document we learn that they've moved house between 1841 and 1845. Now they're in Market Street, circled in green below:

It may be a bit nicer than Little Surrey Street, but not much: 'very poor' or 'poor' dominate.

Let's take another gander at that Parish Register.

Market Street is in the parish of St George the Martyr, but the christening takes place a mile or so north of Catherine's home, in the church of St John Waterloo; perhaps this is where her husband James' elderly parents live. In any case, we need to take a look at this new location, a little south of Waterloo Bridge:

Here's a nice engraving of St John's church by J Cleghorn, published in 1828. It is described as the 'New' church on Waterloo Road, because it was quite new; built 1824.

Here's the modern view of St John's church, looking straight up the road towards Waterloo Bridge. The shiny building on the left is the Imax cinema at Waterloo.

On 07 April 1847, another girl is born, Elizabeth Cunningham, in the civil parish of St George the Martyr, Southwark, and may have died very young. It is yet to be determined if this is another child of Catherine and James.

In December 1848, Catherine gave birth to another daughter, Jane, at St George the Martyr, Southwark.

Here is where things got difficult for the amateur family historian. I couldn't find James and Catherine in the 1851 census, or ever again. Sure enough, there were two James Cunninghams who died in the late 1840s in Southwark; this could be father and son. But there was no death for any Catherine Cunningham. However, in the 1850s there were three Catherine Cunninghams who died in Southwark and Lambeth.

So that's where I left it. The early version of this page speculated that Catherine's husband and son had maybe died in the 1840s and that she had possibly died in the 1850s... not at all a rare occurrence in Lambeth.

But they weren't dead - far from it...

Click here to continue this story and to discover what became of Catherine and her family.

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... or would you like to discuss any of the history... or if you have any observations or comments... all information is always welcome so why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'Showbiz Partletons' Theatre Page