James Partleton (1806-1873) in 1851

In July 2007 Terry Partleton and I crossed Kew Bridge on a short car journey from from the National Archive at Kew, to Hounslow on the north side of the river.

The National Archive holds Birth, Marriage and Death, along with many other records, but it doesn't really hold Parish Registers. And it was a Parish Register we were after, held at Hounslow Library; the parish register of All Saints Church, Isleworth.

In censuses, James Partleton (1806-1873) consistently gives his place of as Isleworth, which in 1806 was a village on the north bank of the Thames, 10 miles to the west of London, circled in red in Leigh's 1819 map below. This location is hard to understand because at this time the family is living in Westminster, circled blue:

All Saints Church can be seen on the Thames riverbank in the Victorian map below. There is a nearby island in the Thames called Isleworth Ait:

This map was created in 1871 and we can see that - 65 years after the birth of James - Isleworth is still just a village surrounded by fields. Below we see two images of the church, an engraving of 1750 and a painting of 1852:

Here's how the scene looks today. The church was destroyed by a fire in 1943 and rebuilt in 1970. The tower still appears to be the original:

So, back to Hounslow Library, which is located in a modern shopping mall. Terry and I had anticipated a lengthy search through the All Saints Parish Register, trawling through long lists of barely legible names, but it turned out that the library had kindly created an alphabetical index, and, - lo and behold - straight away, there was James Partleton, christened in the church of All Saints on Thursday 29 May 1806. His date of birth was 21 April 1806.

James' christening record showed that his parents were house painter Benjamin Partleton (b1774 Westminster) and his wife Catherine Iremonger.

This creates a small mystery. Benjamin and Catherine lived in Westminster: why on earth was James christened in Isleworth?

That question was resolved in 2012 when evidence emerged that James' mum Catherine Iremonger was originally from the village of Isleworth; indeed, James' grandparents Stephen and Katharine Iremonger were still living there in 1806. James was only in Isleworth for the christening: he grew up in Westminster. In 1814 at age 8 we know that he's living in Swallow Street, off Piccadilly, circled in green in the map below:

Let's step into James' shoes for a minute and go for a little walk down the road where he lived.

He'd recognise the stables in the picture below - a major feature of Swallow Street - the former Major Foubert's riding school, painted by an anonymous artist in c1801:

The viewpoint of the artist as he drew Major Foubert's riding school is from the point of the purple arrow in Richard Horwood's London map below. James grew up at no 43, near the junction with Beak Street, circled in green:

Swallow street was a very busy thoroughfare connecting Piccadilly and Oxford Street, notoriously muddy and, though it looks straight enough in the map, in reality was very hard to navigate with your horse and cart.

It was quite a well-known street in London, and is often referenced by writers at the time as a landmark to help the reader, as in this article printed in The Times on 30 September 1806, when James was but six months old:

Left: The Times, 30 September 1806

Left: The Times, 30 September 1806

If I may be permitted a joke at this point, I believe this gentleman above took quite a long time to die because he had to get out and go to the toilet six times before he drowned.

Another interesting story about Swallow Street in The Times reminds us that if young James met a nice doggy in the street, his alarmed parents probably cautioned him very severely to be careful:

Left: The Times, 30 December 1795

Left: The Times, 30 December 1795

In James' lifetime, rabies was relentlessly, unremittingly deadly. If you were bitten by a rabid dog, you always died - every time. There were no exceptions, no matter how small the bite. Rabies has terrible, agonising and terrifying symptoms - and is still is 100% fatal today without immediate medical attention. In the story above, the victim was suffering so shockingly, the doctors, knowing his fate, chose to 'free him from his existence'.

Rabies was eradicated in Britain after 1902 - until a man in Scotland was bitten by a bat in 2002 and died from rabies as a consequence. That's the only infection in Britain in the last 110 years.

In the picture below, painted by Thomas Shotter Boys in 1842, we get a great view of Piccadilly. The blue arrow in the map above shows the artist's viewpoint.

We can just make out the spire of St James Church, above the buildings on the right, where all of James' brothers and sisters were christened. Swallow Street is directly opposite the church on the left-hand side of the road. So, step into James' shoes into the bustling thoroughfare of Piccadilly, exactly as he would have known it!

Here's another contemporary picture of Piccadilly, a comic cartoon of 1818 depicting the crowding and traffic problems:

Noteworth in the above picture is the figure at the far left. Even in James' day, black people were commonplace; there were already 25,000 black Londoners.

In the nice detail below, we see that black people existed in all social classes, including the well-to-do:

That's probably enough about Piccadilly, because from here on, the fortunes of James and many other members the Partleton family are about to head downhill.

James and the other older brothers Thomas, Benjamin [my g-g-g-g-granddad] and William all became house painters like their dad.

By the 1820s, due to the demolition of their home on Swallow Street, the Partleton family migrates from Westminster to the poorer area of Lambeth, south of the river, circled in yellow in the map below:

James' older brothers Benjamin and Thomas are both married in Lambeth in 1822 and 1823.

But we know that James wasn't always a house painter. He started off as a teenager on the stage, which we know from a playbill of 13 May 1825. James is 19 years old:

,%20Saturday,%20November%209,%201889%20reduced%20version.png)

It's surprising the different ways in which vital information is preserved. The above newspaper article was published in the year 1889; it is reminiscing about events which had happened 64 years previously in 1825. This is the tenuous means by which we know James went on stage.

Anyhoo, we know exactly what the theatre looked like on the night when James appeared, because artist Daniel Havell painted it on an atmospheric evening in 1826:

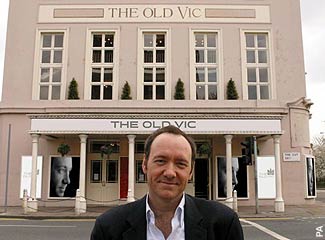

You probably won't recognise the name the Royal Coburg Theatre, near Waterloo Station, where James appeared in 1825, because in 1833, it was renamed the Royal Victoria, which probably still doesn't help much... but you probably will recognise how it is known today; The Old Vic:

Here's the interior of the theatre as James would have seen it during his performance there. It had a very entertaining gimmick called the 'Looking-Glass Curtain'; the audience saw an apparent reflection of itself painted in the curtain as they looked towards the stage:

The Old Vic was noted for bringing theatre to the common people as we see in the [later Victorian] picture below:

Let's have another look at that newspaper cutting:

,%20Saturday,%20November%209,%201889%20reduced%20version.png)

James executes a Terzette Chinoise. "What's that?", I hear you ask, and it turns out that it is an ambiguous description. A Terzette is certainly a a trio, but it can be either musical or dancing. I think the fact that James "executes" the Terzette suggests that he's dancing, and that one of his partners was his brother, but we can't tell which brother.

The Old Vic has been in the news quite a bit since 2004 when Hollywood actor Kevin Spacey became Artistic Director.

At some time in his 20s, James leaves home in Lambeth and heads back north of the river to the area of The Strand, circled in blue below:

James' marriage record has not been located yet, but in 1836 or before, he marries Mary Ann Garrad, who had been married before: her married name was Mary Ann Palmer. It may be that Mary Ann was not divorced or widowed, which would explain why there is no marriage record with James Partleton. Mary is from Lambeth.

Their first child, James, is born on 5 May 1837 in the area of Drury Lane, The Strand.

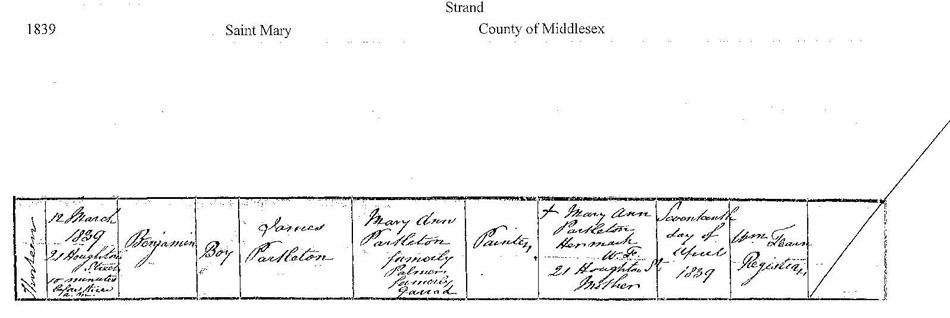

On 12 March 1839 at "ten minutes before three a.m.", Mary Ann gives birth to twins, Benjamin and Charles; below we see Benjamin's birth certificate:

Mary Ann signs with a cross. The family is living at 21 Houghton Street, seen below:

Houghton (Haughton) Street is circled in the map below. The exact location of their house is known: No 21 is shaded in blue in the map. It's the house which is boarded up - 66 years later - on the right in the above 1905 photo of New Inn Passage:

As James stepped out of his front door, we may step into his shoes because we have images of the two houses directly opposite, a drawing [c1913] by the artist Myra Hughes of No. 3 Houghton Street and a photograph of No. 4 Houghton Street:

And if I shamelessly montage these two images using my most amateurish Photoshop skills, with apologies to the artist, we can stretch our imagination, we may step into James' shoes, cross Houghton street in 1837 and make our way down New Inn Passage which we see as the alleyway directly ahead under the signwriter's sign:

On 8 May 1841, James and Mary Ann have their first daughter, named Mary Ann after her mum.

One month later, on the evening of 6 June 1841, the England census takes place. The family have moved to Feathers Court, circled in green on the map above. This is great news for us because we have a marvellous 1840 print of Drury Lane drawn from the viewpoint of the yellow arrow, right outside Feathers court:

The picture is of the Cock and Magpie, No 88 Drury Lane, the location of which is highlighted in yellow in the map. In the distance we can see the steeple of the church of St Mary-Le-Strand... step into James' shoes!

Below we see the census sheet of 1841:

Examining the census record, the enumerator has made several errors. If we compare this with the christenings which we see below, we find that it's very muddled up!

Three weeks after the census, James and Mary Ann decide it is high time they had all of their children christened. The baptisms take place at the church of St Mary-le-Strand, circled in the map above in the middle of The Strand:

The family's home is given as 7 Feathers Court, which can also be seen circled in the above map, adjoining the famous Drury Lane of Muffin Man fame... So let's investigate Feathers Court, and see where that takes us.

What did Charles Booth, the celebrated Victorian philanthropist, record of Feathers Court when his surveyor went to inspect it in the later 1800s?

Apparently Mr Booth's representative was not very impressed. These type of London Courts were accessed by dark, narrow archway alleys leading from the street. 'Airless' is the word which sticks in the mind from Charles' description.

Charles Booth was not the only Victorian reformer to examine the home of James Partleton; here we see a paragraph from London Shadows: a Glance at the "Homes" of the Thousands, written by George Godwin in 1854:

Below we see a hilarious 19th century representation of some of the 'troublesome inhabitants' of Drury Lane of which, no doubt, the neighbourhood association were so keen to be rid - prostitutes, pawnbrokers, drunks, cowboy builders, and beggars:

Drury Lane had always had a unique reputation in London which can be witnessed in this equally hilarious snippet of the year 1760 which I found at the British Library:

"Double Ruffle Cuffs and never a Smock to their Arse" I presume translates to the 20th century "Fur coats and no drawers".

I stayed on Drury Lane recently and I can attest that, with its theatre neighbourhood, Drury Lane retains some of the lively tradition depicted above: people overflowing out of the pubs on to the street on a Saturday night. I wasn't awake at at five in the morning, but I believe it is much quieter these days.

Below is a print of the Drury lane Theatre in 1850;

which can be seen just around the corner from James' house, if you inspect the map below:

Two more girls are born while the family is still at Feathers Court; Sarah in March 1843 and Catherine in March 1845.

Shortly after this, James and Mary Ann receive a terrible blow when their little girl Mary Ann dies aged 4 years old.

Mother Mary Ann signs for the death certificate of her little daughter with a cross. Phthisis, according to Wikipedia, is tuberculosis.

A week later, Mary Ann is buried:

The devastation caused by TB is plain in the above burial record. Not just our Mary Ann, but four other little children from Feathers Court are all buried between 6 September and 26 September 1841. James Spence aged 3 is the child of one of the Partleton's neighbours who can be seen in the 1841 census.

The children are buried in a cramped overloaded burial ground: Russell Court, Drury Lane, which is circled in red in the map below:

Russell Court Burial Ground is claimed to be featured in Charles Dickens' Novel,

Bleak House. Step into James and Mary Ann's

shoes if you dare, for the funeral:

Tait's Edinburgh Magazine has preserved for us an image of Russell Court Burial Ground, published in 1848:

Years earlier, in the 1830s, the Chadwick Report on the state of Londonís churchyards exposed a terrible state of affairs. Chadwick comments:

And Chadwick comments on the bigger situation which faces the whole of London:

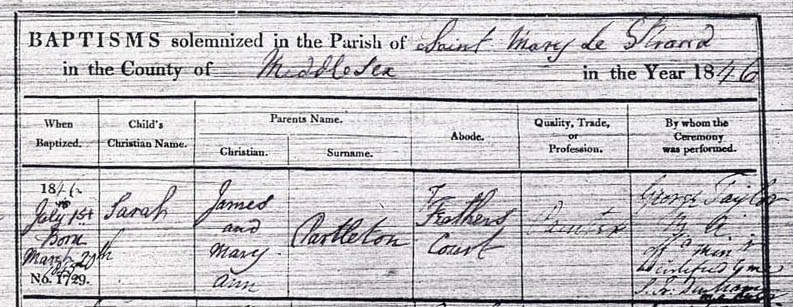

In July 1846 we see the christening of little Sarah Partleton who is now 1 year old. The family has been living at Feathers Court for five years:

During 1846/47 we know that James and his family move south of the river to join the rest of the Partleton family in Lambeth. We know this because their fourth son, John, is born on 2 May 1847 at 13 High Street, Lambeth. Below we see a superb photograph of High Street Lambeth. Step into James' shoes:

In January 1849, James and Mary Ann produce their fourth daughter, Louisa Harriet. Tragically, later in the same year, little Sarah dies aged just 4 years old, a victim of the 1848/1849 cholera outbreak in London.

In early 1851, Louisa Harriet Partleton also passes away aged just 2.

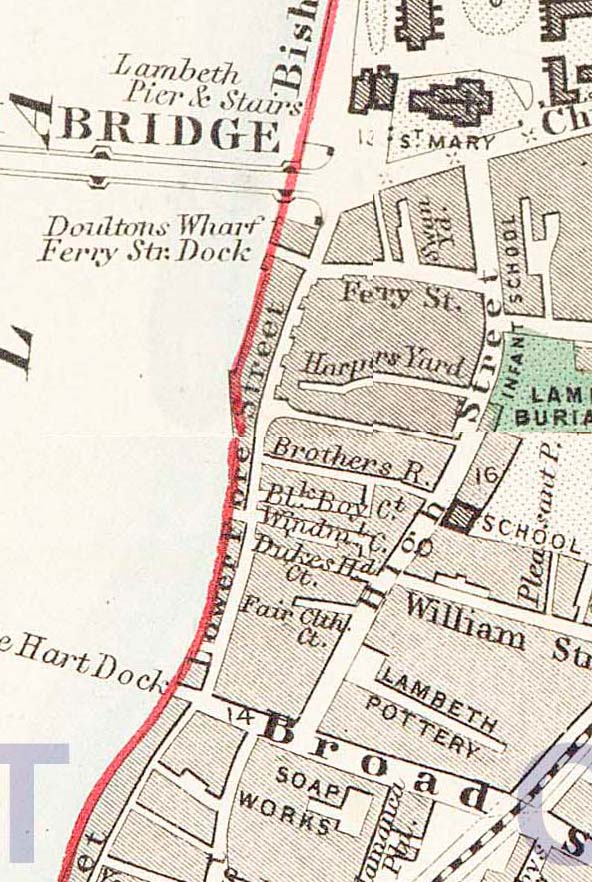

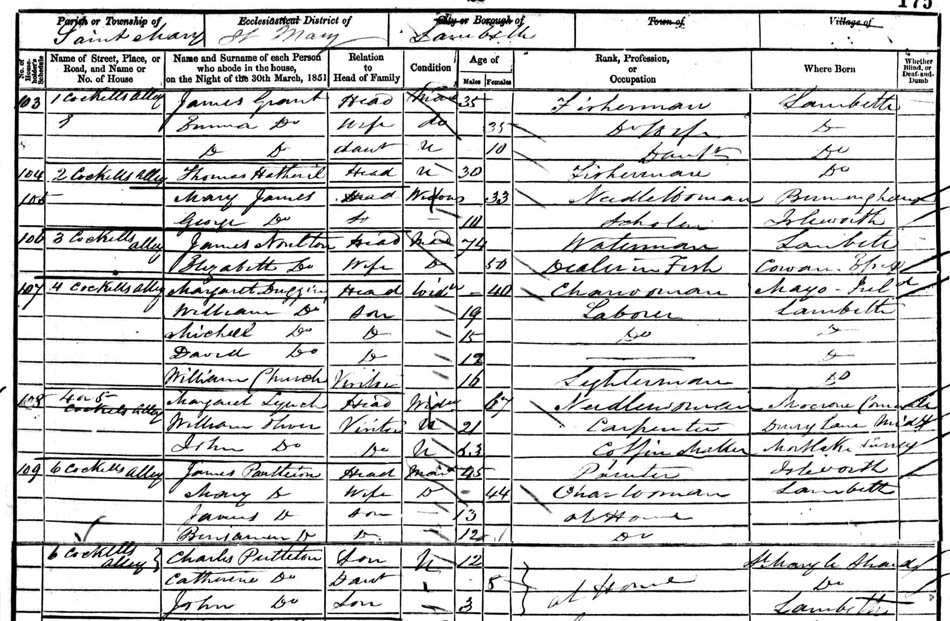

On the evening of 26 June 1851, the census is held in England. James and his family are living at 6 Cockills Alley, an alleyway leading off Lower Fore Street.

Below is marvellous photo of Lower Fore Street taken about 1860; we are standing just north of Ferry Street, looking north, and we can see St Mary-at-Lambeth Church.

The church, and Lambeth Palace in the background, are still there today but everything in the foreground is now unrecognisable; tiny slums all swept away by the development of the Albert Embankment in 1866-1870.

Here is a map of Lower Fore Street, 1862. The first Lambeth Bridge is brand new, completed 1862 (A narrow suspension bridge, it was rather unsuccessful). In 1851, when James lived there, there was no bridge; you had to get a boat across the Thames from Ferry Street in Lambeth to Horseferry Road on the west bank of the river, or take a walk up to Westminster Bridge a mile to the north.

Cockills Alley appears not to be named on the 1862 map but we know for sure that it lies between Brothers Row and Broad Street. (Enumeration District 9). In fact, examination of earlier maps shows that it is the earlier name of what is called Dukes Head Court on the map below. Previous to that, it had been called Coquets Alley. Make what you will of that.

If we turn around on the same spot and face south, as did our photographer - William Strudwick, a genius, to whom we offer our gratitude - in 1860:

Now we are looking south down Lower Fore Street. The kerbstone of Ferry Street is just visible, turning to the left at the bottom left of the picture. James' house in Cockills Alley is just a few yards behind the premises of Clasper, Bain & Clasper, Boat Builders.

There was no fresh water provision in Lower Fore Street. Folk used to go to the Thames with a bucket and drink that. How do we know this? Because, unsurprisingly, a Lower Fore Street resident became the third victim of the 1848/9 London Cholera Outbreak as reported in the words of the John Snow, the legendary Victorian pioneer of public health:

In the preface to his book, John Snow earnestly appealed to the medical profession to pay attention to his research:

But his correct analysis of the cause of the spead of cholera - transmitted through drinking water polluted with excreta - was not widely adopted and it was 20 years before it was properly recognised. Consequently James Partleton would continue to have his share of this unintentional culinary component.

Below is James Partleton's census record of 1851 at Cockills Alley. Mary Ann is heavily pregnant with her fifth son George, who was born a few weeks after the census was held:

It's been possible to track the James and his family in censuses thanks to the amazing records held by Ancestry.co.uk. If you're inspired by this website to seek out your own British ancestors as I have done, click here.

Note that there are no less than three widows (aged 67, 40 and 33), and aptly, a coffin maker, among the twenty people on this census sheet. James Jr. (aged 13 on this page), was later to die in the East End of London, aged 39, leaving his wife a widow, with disastrous consequences, but that is another story which can be found on his page on 'In Their Shoes' on the Partleton Tree.

Finally, incredibly, we can actually get a closer look at Cockills Alley. We are looking north, straight up Lower Fore Street.

The covered walkway across the street connects the premises of J. Stiff & Sons Pottery. They made stoneware - here's an example of what was going on in that factory.

The walkway, and the overhanging building which it joins, can also be seen in the distance in the south-facing view at the top of this page.

Well, I don't know about you, but I'd be a little nervous about going down that alley, at any time. Imagine it on a dark night, gaslight flickering... but let's be brave and sneak a closer look.

If you think you can see ghosts in this picture, maybe it's James. Actually, getting a successful photo of this shadowy alley in 1860 is a real tribute to the photographer. The exposure time might have been five minutes, during which some people walked through the shot and paused for a while.

The archway marked with the yellow arrow is very close to Cockills Alley. I think we can see the kerbstone turning to the right. If not, we are definitely within 20 feet of it! Step into their shoes!

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'In Their Shoes' Page.