George Partleton (1851-1871) in 1871

On Sunday 02 April 1871, the census was taken in England. On this night, George Partleton, aged 20, was living with his parents at 26 Albert Embankment, Lambeth.

Six months later, in November 1871, George was dead.

But, let's start at the beginning. George was born in Lambeth, circled in yellow in the map of London below, which can surely be no surprise to anyone familiar with the Partleton Tree.

The birth was in the July quarter of 1851.

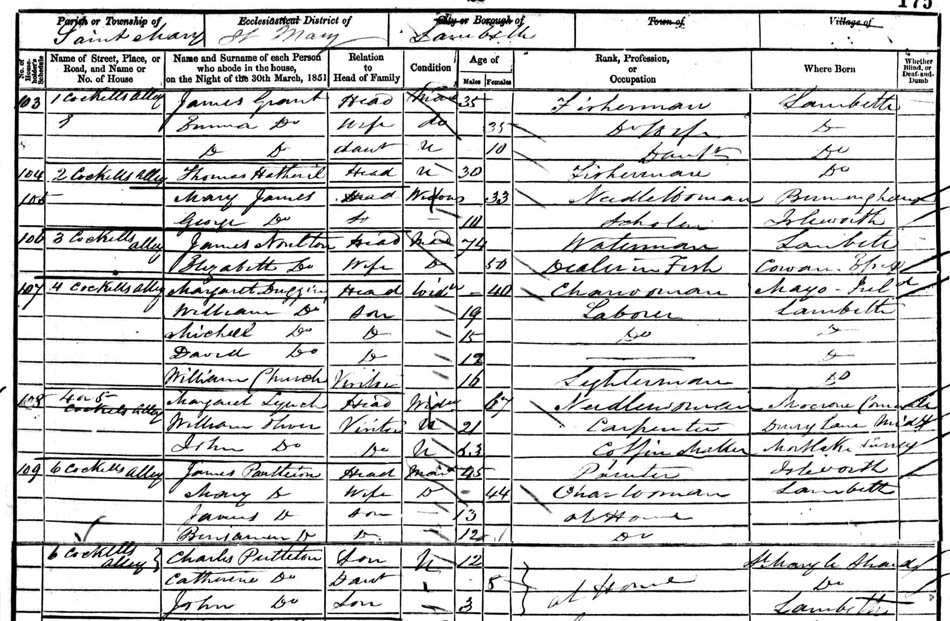

In the 1851 census, held on 30 March, which we see below, George's mum - Mary Ann Partleton nee Garrad - was pregnant with our George. Being pregnant does not stop Mary from continuing with her job of charwoman, ie cleaning lady:

George's mum and dad, James Partleton and Mary Ann Garrad, were probably the poorest couple in the Partleton family. They had moved in 1847 from Drury Lane, north of the River Thames, to Lambeth, south of the Thames.

The river would dominate their domestic situation in Lambeth for years, by flooding their houses and we'll come to that later

The three houses which we know the family occupied were among the oldest (and, in George's day, most decrepit) in Lambeth, located right on the bank of the Thames within the blue and red circles in John Stow's lovely 1720 map:

The property where George was born in 1851 was in Cockets Alley, circled in blue in the map above. In Rocque's 1746 map, it is named as Coquet's Alley, and since it was a dark, riverside alleyway surrounded on all sides by pubs, we might speculate that this is a reference to prostitution. Or it might just have been someone's name.

This web page began as the story of George Partleton, but as I write it, I find I am going off course... way, way off course. In fact, and for a long while, the page is going to become a history of the River Thames. The reason for that can be seen in the yellow arrow in the engraving below, which we may follow like the white rabbit:

The yellow arrow points down Fore Street, which we see below, photographed by William Strudwick in 1860:

The picture was taken from the viewpoint of the red arrow in the map below:

And, as William Strudwick turned his heavy camera and tripod around and pointed it north, here's the view from the same spot, at the point of view of the green arrow:

Fore Street led directly to George Partleton's house, circled in blue in the map below, in Cockets Alley:

Young George's residence was inundated by the Thames on that day, and on many other occasions, so - fair warning - we are now going to take a huge diversion into the watery world of the River Thames. It will be some time before our George Partleton resurfaces.

In ancient times, the stretch of the river next to Lambeth had been much wider, and had flood plains on both banks. Indeed, the river was so shallow at this point that it could be forded at low tide...

Of course, that photograph is not the Thames at Lambeth, but if we put ourselves in the shoes of an ancient Briton, this is a pretty clear view of what he was faced with if he needed to cross the river.

Before the Romans came to Britain, if you didn't have a boat, then marshy Lambeth was the best place to cross the Thames.

One potential crossing point, circled in green as 'FORD?' in GordonxHone's (Victorian) sketch of the ancient Thames below, is at the location of modern Lambeth Bridge. It was opposite Thorney Island, a large shallow island occupying the whole western bank the Thames, long gone - but it was still an island when it was first occupied by Benedictine monks in the AD960s - hard to image now, but, the antecedent of Westminster Abbey was built on an island. The island, shaded yellow in the map below, was created by alluvial deposits at the confluence of the River Tyburn as it flowed into the Thames and branched into two rivulets:

Indeed, the ford was so useful before Roman times that it is tempting to consider that it may have formed part of one the most important ancient roads in Britain, which the Romans adopted, improved, and named Watling Street, shaded in red in the map below:

That's a nice map, but we are interested in the bit where the ancient road crossed the river Thames...

The map above shows the limitations of our knowledge, at the time of writing [2013] - and probably for some time to come.

At the bottom right, the road from Dover, the Old Kent Road, - the A2, to use its modern designation - enters present-day London, shaded in red. It was there as a trackway - an unmetalled road - long before the Romans arrived. Likewise, we see the Edgware Road entering from the north at top left, very straight indeed in its modern topography, as the Romans surfaced and straightened the ancient trackway according to their liking for straight roads, ending at present-day Hyde Park Corner. But in the middle, the prehistoric route of both roads, passing through Lambeth, is lost to history, obscured by centuries of development.

After the Romans invaded Britain in AD43, they had legions of these guys...

... and we are going to step into his sandals - but we'd frankly prefer not to wade up to our waist in the cold muddy river at low tide. And it clearly wasn't practical to have men and horses and supplies ferried in hundreds of boat trips.

It was standard military practice for Roman armies to create floating pontoon bridges to enable their advance, and its likely they did this across the Thames soon after the invasion. Certainly within 12 years of their occupation, in about AD55, they had built the first permanent London Bridge, on wooden piles, approximately 60m east of the current London Bridge location, where some of the original timber foundation piles have been excavated. But there was no London at this time, indeed no significant settlements at all: they chose the bridge-site, in the open countryside, because it had the best landing places on both banks of the river.

Below we see the route our legionnaire took as he traversed the countryside from the south to the north, across the new bridge. We can see the main connection on the north side from the bridge to Hyde Park Corner ran along modern High Holborn and Oxford Street. I was working in an office on High Holborn for 6 months, earlier this year, oblivious to its history:

While the Romans built their bridge, a settlement formed on its north side: Londinium, the foundation of modern London.

The Roman London Bridge of AD55 would not last forever. In fact it may have only lasted 5 years - as it was probably destroyed in the revolt of AD60 when Boadicea's tribesmen sacked and burned the small nascent Londinium settlement on the north side of the bridge in her revenge attack. After the Romans defeated Boadicea, they rebuilt the bridge, and it remained the vital river-crossing for the Romans for 350 years.

By overlaying Hone's map, below, we can see the the extent of Londinium, about 150 years later, when a wall was constructed around it, some parts of which still survive. Hover your mouse on-and-off the map, and you'll see the extent of the old walled city, shaded in yellow, in its context within modern London:

Having connected the two ancient routes, and straightened them, and improved them, the Romans called the whole north/south roadway Watling Street.

All changed after the Romans withdrew from Britain in the early 400s AD. During the economic collapse which followed their departure, London Bridge fell into disrepair - presumably gradually at first - but total in the end. The Saxons invaded in the decades which followed: the north bank of the Thames eventually became part the kingdom of Mercia, and the south became the kingdom of Wessex. The mutual hostility of these kingdoms may have been a factor in the bridge's demise, and surely a dampener on any idea of rebuilding it. Thus is came to pass that there was no bridge at all for 500 to 600 years, from the early 5th century until about AD 980.

So, with no London Bridge, we are back at marshy Lambeth. We stand on the site of Benjamin Partleton's house at Crooket's Alley at Lambeth and look towards the Houses of Parliament - but that is 1400 years in the future:

The ford which crossed the river near Lambeth - and there may have been more than one ford and ferry on this stretch - had never gone out of use even when London Bridge was built.

After the Romans left, the Saxons obviously routinely crossed this reach of river, even if they didn't like the folk on the other bank. So, we're back to those ancient trackways, and those missing sections of road...

It's obvious that the trajectories of the Edgware Road and the Old Kent Road in the map below are wholly different, and from that I'm going to infer that the development of the two routes is unconnected: they were never specifically designed to be directly paired up:

It's surely unproductive to speculate about which of many possible paths the lost ancient roads took to get across the Thames...

...but the temptation is irresistible; let's project the straight route of the Edgware Road to the river. I have charted its trajectory in green in the map below:

The projected line of the Edgware Road ends up at modern-day Vauxhall Bridge, and it turns out that there is one interesting nearby feature which is worth exploring.

I mentioned earlier that the first permanent London Bridge was built in AD55, but that may not be true...

In 1993, bronze-age wooden piles were discovered, preserved, submerged in the riverbed mud at Vauxhall. Their location is in the blue circle in the map above. Eight years later, Channel 4's Time Team visited that riverside site. I loved that show, now departed.

Time and tide wait for no man, and during the making of the program, which was broadcast in January 2002, the ancient posts were only revealed for a couple of hours on an especially low tide on the Thames. Time Team successfully used the opportunity to excavate and remove one of the piles which we see in the photo below. They replaced it with a modern marker. Ouch, quite destructive, yes, but archaeology is destruction, as they often say in the show.

The piles are pretty substantial. They were originally huge - well over a foot in diameter - and there are 20 of them, somewhat confusingly scattered in arrangement, but in general forming two rough parallel lines, approximately 4 metres apart, marching 18 metres into the river. The pile excavated by Time Team was found to be sharpened at the bottom to allow it to be driven into the riverbed; the ancient toolmarks were still clearly visible.

It's hard to imagine that this structure could be anything other than a bridge, which would have the potential to island-hop across eyots in the river, formed by the confluence of the nearby river Effra with the Thames. But actually it could be a jetty, which would be useful for a ferry. The wood has been carbon-dated to circa 1500BC. The structure was gone when the Romans arrived in AD43: it was as ancient to them as the wooden Roman bridge is to us.

Below we see a modern jetty. The piles in the picture are less than 2 metres apart. Imagine them 4 metres apart, as they were at Vauxhall, and that 3500 year-old structure - be it bridge or jetty - takes on truly impressive dimensions. Those bronze-age people were resourceful:

So now we know. The ancient location of Lambeth was a low-lying marsh, used a crossing point to get across the wide river - much wider than it is now.

The origin of the place-name Lambeth isn't known, but I'm going to dip into the world of etmymology, which gets pretty murky at its edges. There are some theories, as is usually the case when it comes to etymology, and frankly I'm a sceptic, so forgive my jaundiced eye. When the actual origin of a word or name is not demonstrable, theroies emerge from the gloom, inevitably wholly contradictory with each other, and unsupported by facts. One derivation I have found is that Lambeth originally meant a crossing-place for lambs, which doesn't bear close scrutiny. The Thames ain't that shallow even at low tide. For a sheep to walk across the river, the Thames would have to drop to a foot deep - not gonna happen. The poor little wooly jumpers would drown.

A somewhat more convincing offering is that Lambeth comes from Lam-hithe, meaning muddy landing-place, (Old English lam = mud, the same root as loam), plus hithe (an Anglo-Saxon coastal or riverside placename signifying a port or haven, eg Hythe, Rotherhithe). Who knows for sure? Not I.

Left: Dictionary.com's view of the derivation of Hithe, citing their source as Pennant

Left: Dictionary.com's view of the derivation of Hithe, citing their source as Pennant

Details of the eventual building of a new bridge by the late Anglo-Saxons are sketchy but it occurred between 970 and 1014. Since that time, despite collapses, rebuilds, fires and disasters, London Bridge has been in continuous service. For 750 years, through the whole medieval period, it was the only bridge across the Thames in London.

The medieval bridge is nicely apparent in the lovely map of London we see below, drawn in about 1560 by an anonymous author:

The above map gives us a perfect view of London in the reign of Elizabeth I.

Here's an Elizabethan shoe:

"Why are we looking at an Elizabethan shoe?", I hear you ask.

It's a fair question, and I'll answer by saying that we are going to slip a pair of those shoes on and try to cross the Thames from the south to the north in the time of Elizabeth I:

We can see from the map that the land south of the Thames was sparsely populated. Indeed, developed areas on the south bank of the river were specifically excluded from being considered a part of London, and had completely separate names: Southwark to the east, and Lambeth to the west.

Being separate from the City of London was very convenient because London had strict laws - ordinances - including some which restricted theatres and other places of entertainment. And thus it was that several of these establishments sprang up outside the jurisdiction of the City of London, in Southwark. Londoners would cross London Bridge for a night out of fun.

Unfortunately folk in those days had a rather different idea of what constituted a square night's entertainment, including watching bear-baiting and bull-baiting, circled in blue:

The shoe we just saw was was found during the archaeological excavation of the Elizabethan Rose Theatre near the southern end of London Bridge.

Which brings us nicely to London Bridge itself, the only bridge over the Thames. The person wearing that shoe saw London Bridge exactly like this:

The beautiful engraving above was drawn in 1616 by Dutchman Claes Visscher; we can see that when we cross the river, it will be an experience which is more like passing though a tunnel than traversing a bridge. We will scarcely see the river at all as we pass through the buildings;

To our contemporary eyes it is hardly recognisable as a bridge at all... we don't have houses, shops and a chapel brimming over every square inch of our modern bridges, which are usually - by design - functional and featureless.

The present-day London Bridge, which was built in 1973, has no pretensions of glamour:

Though it is undeniably prettier by night...

The London Bridge which existed in George Partleton's day was the one we see below, known as Rennie's Bridge after its architect:

Rennie's is the London Bridge which has ended up in Lake Havasu City in America, snapped by the author on holiday in 1980:

"Where's our George?", I hear you say, but we shall have to be patient 'cause he's not yet born for 1440 years...

The Thames is significantly tidal, and its flow was seriously constrained by bridges:

The ancient medieval London Bridge we see above was sadly demolished in 1831, twenty years before our George was born. Its 19 arches, 17 of which we see in the engraving, requiring 20 piers, caused a serious obstacle to the water flowing underneath. At times the river was six feet higher on the upstream side and it could be fatal to try to navigate a boat through the rushing rapids pouring under the arches.

Although the replacement of London Bridge in 1831 significantly reduced the obstruction, the river was further hindered by the 18th and 19th century proliferation of new bridges; Westminster (1750); Blackfriars (1769); Battersea (1772); Vauxhall (1816); Waterloo (1817); Southwark (1819) Hammersmith (1827); and Hungerford (1845). During the 1850's and 1860's, when George was a child, the river would rise on high tides and flood much of Lambeth a couple of feet deep; the new bridges were blamed as a contributing factor. The houses where George lived were regularly inundated.

Below, from the green arrow in the map above, we see the Illustrated London News published in the year before George was born:

George's house in Crooket's Alley lies just a few yards behind the buildings directly ahead.

One bold (or daft) person in the engraving above is standing knee-deep in the flood, and we know something about the state of this river-water thanks to a hero of this website, Michael Faraday, who is depicted in the cartoon below, published in Punch on 21 July 1855:

Father Thames is illustrated rising from the stinking river covered in excrement, a dead cat upon his head. The bloated carcasses of dead animals bob on the surface of the river.

Faraday is shown giving his card to Father Thames - a reference to the experiment carried out by the great man, as described in his original letter which had been published in The Times two weeks earlier, on 07 July 1855:

Faraday declared that he didn't dare go as far up the river as Lambeth because the stench from the sewage in the water was even worse than it was at Hungerford. The Thames was so full of crap that the white cards he dropped into the Thames to test its opacity disappeared from view before they were even one inch under water.

At the time Faraday wrote his letter, our George Partleton, living in Lambeth, was four years old.

He'd been christened at the Church of St Mary-the-Less on Princes Road, along with his baby brother William, in the February of that year:

Of course, the floods did not go away, nor did the reek. Three years after Faraday's letter, during the summer of 1858, there was a record-breaking heatwave, and as a consequence, the centre of London was engulfed in its worst stench ever.

The conditions experienced by Londoners during that summer became known as the Great Stink, and it caused Punch magazine to reprise its cartoon of Father Thames, in a slightly different form, in their edition of 03 July 1858:

The names of Father Thames' children are Diphtheria, Scrofula and Cholera.

George Partleton's elder sister Sarah Partleton had died, aged 5, at Crooket's Alley, from the much-dreaded cholera, a year before George was born. George was 7 years old during the year of the Great Stink.

George's family were very poor, there's no question of that, so I'd like to try to visualise him roaming the streets, as he undoubtedly did, in all probability barefoot like these street urchins, who are, I guess, about his age, photographed on an unnamed road in Lambeth:

The great picture we see above was taken in Lambeth by pioneering photographer Paul Martin. Paul used a hidden camera which is why the photo has such a superb natural look, although the boy at the front looks like he might have twigged the concealment. We feel like we've travelled back to Victorian times, bumped into these kids whilst walking along the street, and maybe just asked them for directions. Ok, the photo was taken in 1893, twenty-two years after our George Partleton died... but it illustrates the poverty which persisted in Lambeth through the entire 19th century, during George's lifetime and beyond.

The Great Stink had to be dealt with, and the flooding had to be dealt with, and we'll come to that in a minute, but first let's have a look at the sometimes-soggy residences which housed our George as a child, because incredibly, we do have pictures of some of them.

Crookets Alley, where George was born, was also known as Duke's Head Court because of the Duke's Head pub at the Fore Street end of the alley. Amazing but true, we do have a picture of this tiny alley, from Lambeth archive, painted by artist J Finlay in exactly the same year as George was born:

The view above is seen looking towards Lambeth High Street from the viewpoint of the blue arrow in the map below

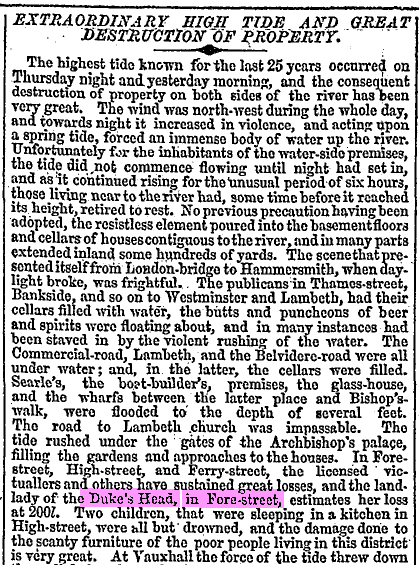

We know George's alley was prone to flooding because it was reported in The Times of 13 December 1845:

How often was young George's house sopping wet? The newspaper report above was due to a particularly big inundation, but in fact the water invaded Lambeth to a greater or lesser extent at least six or seven times a year, every year.

So, the residents of Lambeth in Victorian times had two major problems: (1) Uncontrolled sewage; and (2) Chronic flooding - a very nasty combination.

The solution wasn't going to be cheap, but something had to be done:

When George Partleton was 8, a Royal Commission was set up to evaluate the problem. The Commissioners advertised in newspapers for proposals from developers for the creation of a new raised embankment to keep the river out, principally at the Lambeth section between St Mary-at-Lambeth church and Vauxhall Bridge. Twenty proposals were received.

The Commissioners listened to a presentation from each proposal, including some interesting suggestions as to how the project could be funded, but in the end didn't select any of them, instead using a mixture of the best ideas. Whether the bidders were compensated for having some of their good ideas nicked, I don't know.

More interestingly, the Commissioners also heard evidence from local notables who explained in detail the problems created by the floods, thereby giving us some fascinating insight into the exact streets in Lambeth where our George spent his childhood. The tiny, cramped, housing between Fore Street and High Street - where George Partleton is living - is overcrowded, crawling with humanity. Mr R Taylor, churchwarden of St Mary-at-Lambeth church, questioned by the commissioners, described it as a beehive:

The area prone to flooding described by Taylor is shaded in blue in the map below:

Churchwarden Taylor goes on to explain how the water finds its way into the streets.

But actually, on the really high tides, the water invaded by the most obvious route, up the wharves and slipways, at the points of the green arrows in the map below:

We see the slipway at the end of Broad Street in the photograph of c1860 below:

We are looking from the point of view of the purple arrow in the map below. Incredibly, the house picked out by the yellow arrow in the photograph above is another of George Partleton's childhood residences, 79 Broad Street - outlined in purple in the map below:

Below we see our George Partleton, aged 9, in the 1861 census, living at the above address:

Of note is that 9-year-old George is not at school - compare their descriptions with the Partleton's neighbour of two doors down, publican Anthony Banridge whose four daughters are listed as scholars. George's dad James is a house painter.

The whole of Broad Street was noted for flooding. As we can clearly see, the house is very vulnerable, and the ground floor would be regularly knee-deep in stinking thames-water.

Below we see an engraving of the lambeth foreshore familiar to our George, from the Illustrated London News, to whom we are all obligated for recording images of disappearing Victorian scenes:

What we see above are the Thames-side frontages of properties on Fore Street including Robert Bain's boat-yard just a few short steps from George Partleton's homes on Broad Street and Crookets Alley. The riverside locations in the picture were essential for barge access to transport products from manufacturing businesses by the Thames. At Lambeth, such businesses were commonly potteries; one example is visible in the engraving, next to Bains, which perhaps says Smoke Pottery. The taller building at the end is the Lambeth Rice Mill.

We are looking from the viewpoint of the green arrows in the map below:

The flooding just kept coming back, year after year. In 1881 The Illustrated London News sent an artist to record the effects of recent floods in Lambeth:

George was a potter, which is not surprising, because Lambeth was a centre of a large pottery industry. The biggest contributor was the Doulton company who had numerous factories in the area from 1815 onwards. The photograph below was taken in 1866; the photographer is standing on the new Lambeth Bridge, but the massive redevelopment of of the foreshore in 1866-1870 as the Albert Embankment has not yet started.

The picture transports us to the riverside frontage of Lower Fore Street... fancy a pint in the Ship Tavern? And there is Doultons Wharf which can be matched to the 1862 map below. The frontage is 100% unrecognisable today, having been redeveloped several times since.

George Partleton's dad's house is located on what remained of the original Princes Street, renamed Albert Embankment, at the bottom of the map, between Anderson's Walk and Gloucester Street, on the west side of the railway line, three doors down from the 'Three Horseshoes" pub which has also survived the redevelopment at 1871.

Fortunately for us, our 1866 Victorian photographer was considerate enough to direct his lens northwards straight up Princes Street before any demolition. This would have been a very familiar view of the street where he lived to our George who was 13 at the time of the photograph.

On the left we see just the very top of a bottle kiln - part of John Cliff's Imperial Potteries, and we also see what appear to be some fairly impressive pots on the roof. There were several other potteries on this road.

If we progress a short distance southwards on the map down Princes Street, we come to tiny New Street - with its coal wharf at the end of it. This stunning photograph was taken about 10 yards from George's house. He'd probably recognise some of the little waifs in this shot of 1866.

We don't know where George worked. It might have been at the 'Lambeth Pottery' which can be seen on High Street on the map.

Doultons started by making stoneware drainpipes, later developing into other products ranging from humble everyday wares to very fine expensive pieces. Below is the Doulton stamp '15 High Street Lambeth', stamped on their wares from 1827-1858.

And here is the stamp used (1869-1872) at the time of the George's 1871 census :

Finally, we can see an example of Doulton Lambeth Ware of 1869-72:

And the Stamp on the bottom:

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'In Their Shoes' Page.