Charles Greenwood Partleton (1842-1918)

Part 1

My great-great granddad Charles Greenwood Partleton was born on 26 January 1842, at 8 Francis Street, Lambeth, the youngest of nine children to Benjamin Thomas Partleton (1799-1843) and Mary Greenwood (1799-1855).

Here's the location of Lambeth, circled in blue in John Cary's 1785 map of London:

To get a more precise picture, let's look at Edward Stanford's 1862 map, below, and locate Charles' birthplace - Francis [Frances] Street, circled in red:

Francis Street was late Georgian – built c1820-1830, and, when we think of Georgian housing, we are usually put in mind of fine architecture and elegant proportions. But, of course, not all Georgian houses were like that. The houses on Francis Street were built at low cost, to be let for low rents.

The street only lasted for 100 years before being demolished in the 1930s. Its fate was similar to much of the Georgian development of working-class accommodation in Lambeth, replaced by blocks of flats built in various eras; 1890s,1910s, 1920s, 1930s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s,1990s, 2000s etc. There are a lot of flats in Lambeth.

We do have a pretty good idea of what Francis Street looked like:

The photograph above was taken in 1937, not of Francis Street, but of the next street in the same development - Orsett Street, from the viewpoint of the blue arrow in the map below:

Starting in the 1920s and continuing in 1930s, the London County Council (LCC) were keen to clear the slums from this area. The cheap Georgian workmen's houses on Francis Street, Orsett Street and other roads in the near-neighbourhood were cleared of their occupiers and demolished in the late 1930s, replaced by a development of blocks of flats called the Vauxhall Gardens Estate. Why Vauxhall Gardens?... we'll come to that later.

Let's have a quick look at the location of Francis Street now, courtesy of Google Street View, from the viewpoint of the purple arrow in the map above. This 1920s and 1930s LCC style is called neo-Georgian, and, by the council reports on the internet, Lambeth’s Conservation Officer is much enamoured with it. I’m not so sure myself:

We can learn a little more about old Francis Street with the help of Mr Charles Booth.

Charles Booth was a wealthy Victorian philanthropist who made his fortune in the skins and leather business. He used his wealth to finance investigations into poverty in London, producing excellent Poverty Maps as a part of the process.

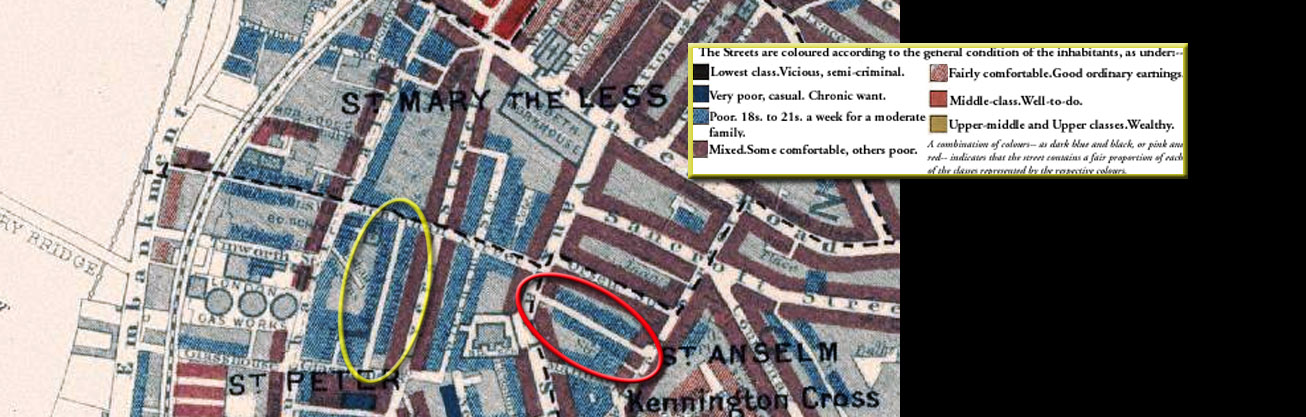

In the 1890s, Mr Booth's investigator took a slow stroll with his notebook down Francis Street, looking left and right, talking to people, and sucking the end of his pencil thoughtfully. The name of Francis Street is not legible in the map below, but - take my word for it - it's the one in the red circle:

Obviously noticeable in the map is that the surrounding area is either 'poor' or 'mixed'. It was not a place where posh people lived, nor even the middle classes.

In common with thousands of streets in London which had common names, between 1878 and 1886, Francis Street was given a new name, to differentiate it from all the other Francis Streets. The chosen name was Frank Street; here are the first-hand notes on Frank Street prepared by Booth's investigator, circled in red:

Decoding the handwriting:

Frank St [Francis Street] : 2 stories : labourers for Myers bedstead factory : lb [light blue] as map.

Booth's surveyor assigned a colour code of light blue, meaning poor, to Francis Street. At least it wasn't very poor. Our gentle readers may have heard of Myer's beds, as they are still in business today. Myer's started in Vauxhall Walk, just round the corner from Francis Street, in 1876 when Charles Partleton was 34 years old, and they finally moved out in 1982.

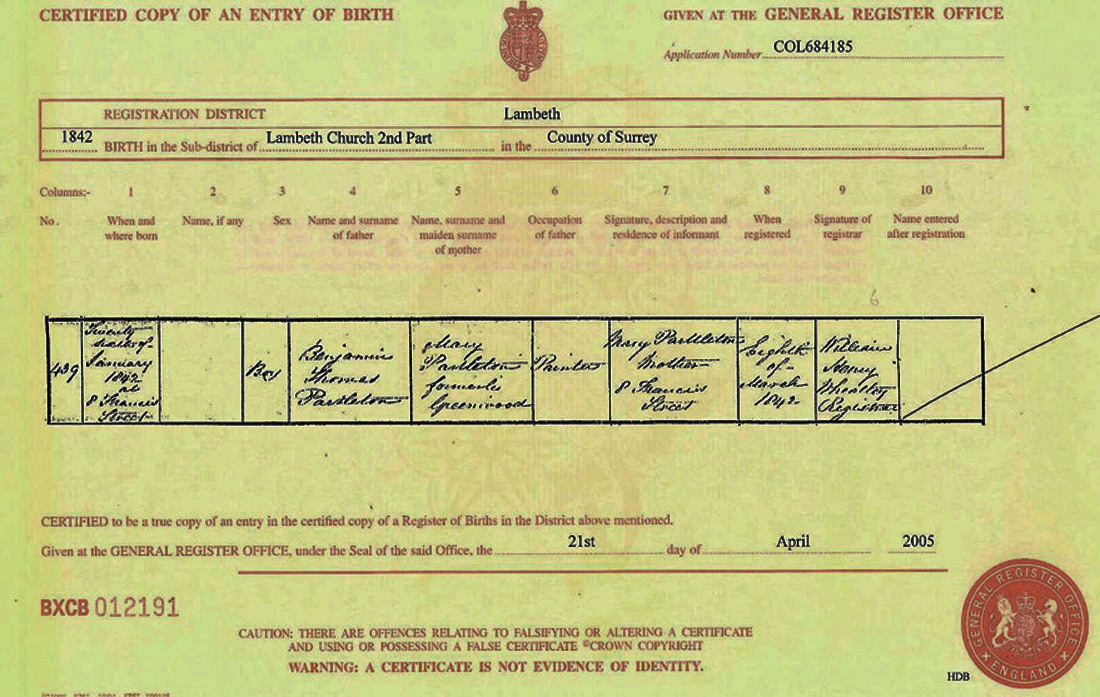

But we have jumped ahead. Charles is not yet 34; he's just been born. Below we see his birth certificate, his address recorded as 8 Francis Street, in 1842, courtesy of Terry Partleton:

Mmmm, what's this ... a birth certificate... with no name on it? Strange but true. Note that the heading of the appropriate column says 'Name, if any '. This is the clue that the objective of this document is to record a birth, not to give a person a name. In the UK, you must, by law, register the birth of a child within six weeks. But it is not a legal requirement to assign the child a name or even to mention one. Nor do you ever have to even at a later date, in the register of births. Like I said, strange but true, and I believe it is still true today. Don't quote me on that.

So, it seems, at the time of registration, the parents - Benjamin and Mary Partleton - obviously still hadn't decided what to call the baby, so this went blank in the record. Maybe they were arguing about it.

Eventually, they named the baby Charles, probably after his granddad - Mary's father Charles Greenwood. Baby Charles was Benjamin and Mary's ninth child. In 1839, they had previously also named their eighth baby Charles, a little boy who had only lived 9 weeks. Maybe that was part of the argument.

Our Charles was never baptised - as far as we can tell - so he wasn't doing very well in the official-recording-of-first-names department! This may be because his parents had other things to worry about: as little Charles approached his first birthday, maybe just started walking, but his daddy Benjamin was seriously unwell:

Charles' dad Benjamin Partleton died of a stroke - 'Apoplexy' - at just 43. Average life expectancy was low in the Victorian era, but this average was partly a product of the terrible rate of child mortality. If you made it through your perilous childhood years, you could expect to live well past 60. So, 43 was a peculiarly young age to die of a stroke, even in Victorian times. If you have seen other pages in the Partleton Tree, you may be aware that Benjamin's stroke may have been brought on by the same cause which killed his brother Stephen: lead poisoning from the paint he was using in his job.

Benjamin was interred at Lambeth Burial Ground on 22 January 1843, four days short of baby Charles' first birthday:

The ceremony was held at Lambeth Burial Ground, outlined in blue in the map below:

Before we set off for the funeral, let's make a short diversion into the history of this graveyard...

There have been churches at the site of St Mary-at-Lambeth since before the Norman conquest, with extensions, refits, repairs, modifications and rebuilds. Here's the version of the church which Charles saw as a child, painted by artist John Chessell Buckler in 1828:

What we may notice is that the church has a tiny Medieval graveyard in its grounds.

This painting was executed as the artist stood in Church Street, from the point of view of the yellow arrow in the map below:

John Buckler also treats us to a clearer view of the churchyard from inside the boundary at the point of the red arrow in the map above:

This gives us an excellent perspective of just how small the graveyard was. Tiny gravestones jostle for space in the few available square yards. How many people could be buried in this space? What do you reckon? I'd say: less than a hundred.

For centuries, as London had grown into a megapolis on the northern bank of the Thames, Lambeth had remained a small riverside village on the marshy southern shore, with just a handful of burials a year. But, by 1705, this little graveyard was ram-jam full.

The Archbishop of Canterbury, whose London residence, Lambeth Palace - as we see below, is right next to st Mary-at-Lambeth church - allocated a piece of land from his diocese for a new burial ground on the High Street, within the area outlined in green in the map below:

It is apparent from the map that the green burial ground was much bigger that the original graveyard fringing the church - perhaps 5, 10, 20 times the size.

But from here on, Lambeth was growing faster and faster, and after a little more than 100 years, the burial ground outlined in green was also filled beyond its bursting point.

In 1813, Parliament was petitioned to allow it to be extended:

Left: Journals of the House of Commons, November 1813

Left: Journals of the House of Commons, November 1813

I've got to remark at this point that, when doing family history research, coincidences abound, which very much adds to the fun. The above petition was referred to parliamentary committee, and the senior committee member was Henry Thornton, circled in blue, who in 1813 was the MP for Southwark, and a famous banker, philanthropist and reformer.

Now jump forward 30 years to 1843, and look at that death certificate for Charles Partleton's dad, Benjamin, whose burial we will be attending soon:

Benjamin died of a stroke while on a painting job at the fabulous grand home of wealthy banker Henry Thornton. Not the same Henry Thornton who headed the parliamentary committee, but his son of the same name, who lived at the same house, Battersea Rise House.

Anyhoo, that was just a coincidence. The parliamentary committee approved the expansion of the burial ground on Lambeth High Street and consequently, in 1815, the parish extended it by buying and demolishing neighbouring properties on the corner of High Street and Paradise Street. The boundary was extended from the green area to the blue area in the map below:

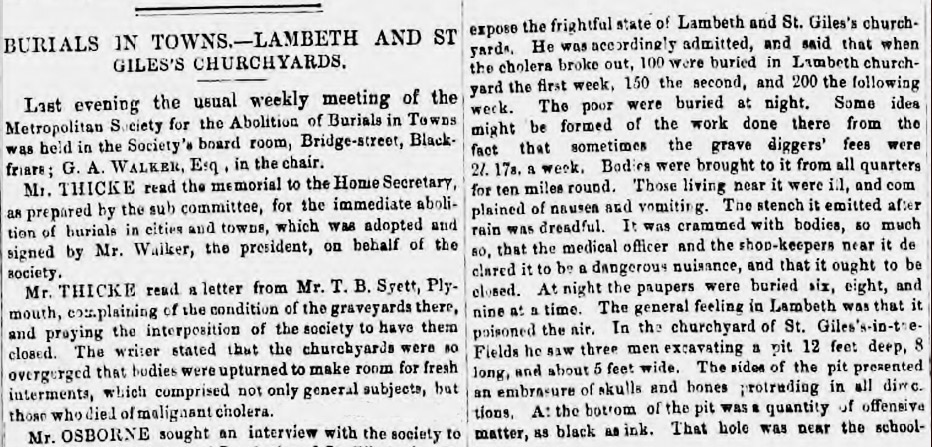

Two years later, we uncover the following extraordinary and terrifying story of events in the new Lambeth graveyard:

I've got to say, those unfortunate church officials must have surely been muttering; "This isn't what we signed up for!"

Shivering in the dark in that graveyard on a cold December night, they can't have relished their task, and then had to face a pitched battle with a psycho wielding a sabre... I love the revelation that 'to his great astonishment', the church sexton John Seager discovered that the grave robbers were the very same men whom he had employed and paid to guard the burial ground!

When we look back at the marriage record of our Charles' uncle, Thomas Partleton, at Lambeth church in 1823, six years after the newspaper story, we see that it was witnessed by the self-same John Seager - who had obviously survived his wounds:

That expansion of the graveyard in 1815 was not going to be nearly enough. The population of Lambeth was erupting with overflow from London, including the Partleton family when the long lease on their previous home north of the Thames expired at exactly this time. The Partletons proceeded to contribute to the population explosion by increasing their own numbers many-fold, and, along the way - to put it bluntly - providing their share of bodies, mostly young ones, for the burial ground.

In fact, from here onwards, demand for burials so far exceeded the available supply, the High Street cemetery became a notorious public disgrace. I have been counting pages in the Lambeth parish burial registers which show that, between 1815 and 1854, 45,615 dead people were crammed into the new extension of the Lambeth burial ground. The maths isn't hard; it amounts to less than 1.5 square feet per body, or to put it another way, 22 times more people than can possibly have fitted into the available space. How did they do it? A shoehorn? A car crusher?

Well, one thing they may have done was to dig deep, really deep. Forget 'six feet under' - sometimes they went 12 feet down, mult-storey funerals. At Victoria Park, a commercial cemetery in East London, they went down 30 feet, and then stacked the caskets in the ground with a thin token of soil between them. Another technique to was to routinely exhume older graves - quite possibly including those of Benjamin Partleton - removing the bones to a bone-house called an ossuary. There was indeed a bone-house at Lambeth - we just read about it in the Hampshire Chronicle. The parish then re-used the ground; and the recycled land effused a gruesome smell of decay:

Left: Bury and Norwich Post, 12 September 1849

Left: Bury and Norwich Post, 12 September 1849

What else could they do with a thousand new bodies arriving every year, all clamouring for a funeral?

In the summer of 1849, the year of the above newspaper report, deadly cholera erupted in unsanitary Lambeth, making a terrible situation much worse:

450 bodies, including that of our Charles Partleton's 4 year-old cousin Sarah - one of the first victims - whose death certificate we see above, had be be buried in the already-full graveyard in three weeks, and we learn a little of the stomach-turning methods which had to be deployed:

Left: London Daily News, 26 September 1849

Left: London Daily News, 26 September 1849

This diabolical mess of burial arrangements wasn't unique to Lambeth, or indeed - as we read above - to London.

So, all of London's tiny ancient cemeteries were being overwhelmed in the mid-1800s by the city's surging population. The ground level of graveyards rose year-by-year and they almost all became noisome putrefying hell-holes. Obviously this couldn't continue...

The 1852 Burial Act was passed, and as a consequence, a date was set for the closure of Lambeth burial ground, after which time the Lambeth dead were not only forbidden to be buried in Lambeth parish, but could not be buried in any parish burial ground within the metropolis of London. This law did not extend to non-conformist graveyards such as those of Quakers and Jews, or to secular burial businesses like Victoria Park Cemetery.

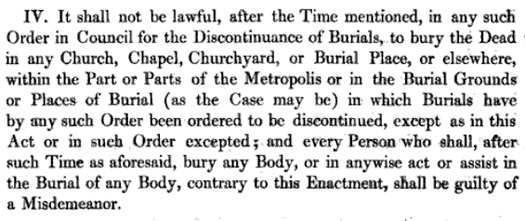

The last entry in the Lambeth burial register was that of 50-year-old John Greenwood, on 31 May 1854, circled in blue below.

We may imagine officiating minister C. Sparkes signing the book, wiping the perspiration from his brow, closing the register with a huge sigh of relief, and giving thanks to God that he would have to oversee no more unholy interrals at Lambeth burial ground. There were 12 burials on that day, and I'm sure that there were 45,615 more sighs of relief from the souls resting in that little spot, who could now actually rest in peace:

On the very same day that poor Mr Sparkes was overseeing those last funerals - Wednesday 31 May 1854 - there was a gathering of dignitaries, including the Bishop of Winchester, six miles away in the countryside at Tooting, to inaugurate the new 30-acre Lambeth cemetery "at Garrett's Lane" (Blackshaw Road cemetery), which cost the parish £9000.

Five years later, on 07 November 1859, circled in red above - apparently in contravention of the Burial Act - Lambeth parish performed a burial in the original graveyard next to the church... were they deliberately flouting the law? The laws of 1852 Act had been very strict and specific, forbidding all further London burials. However, it did have a clause to allow rare exceptions - for existing family plots - which is probably the case above for Mr Pulman above, whose body had been brought some distance from Wandsworth. Even so, the Burial Act demanded that special permission must be sought for this exemption from 'one of the Secretaries of State', probably the Home Secretary.

And so, finally, we return to the funeral of Charles Partleton's dad, Benjamin, in 1843, nine years before the Burial Act. Let's put on a black suit and join Benjamin's grieving widow, Mary Greenwood, carrying 1-year-old baby Charles wailing in her arms. I reckon Mary's brothers will also be in attendance, including William Greenwood who is to become Charles' proxy father.

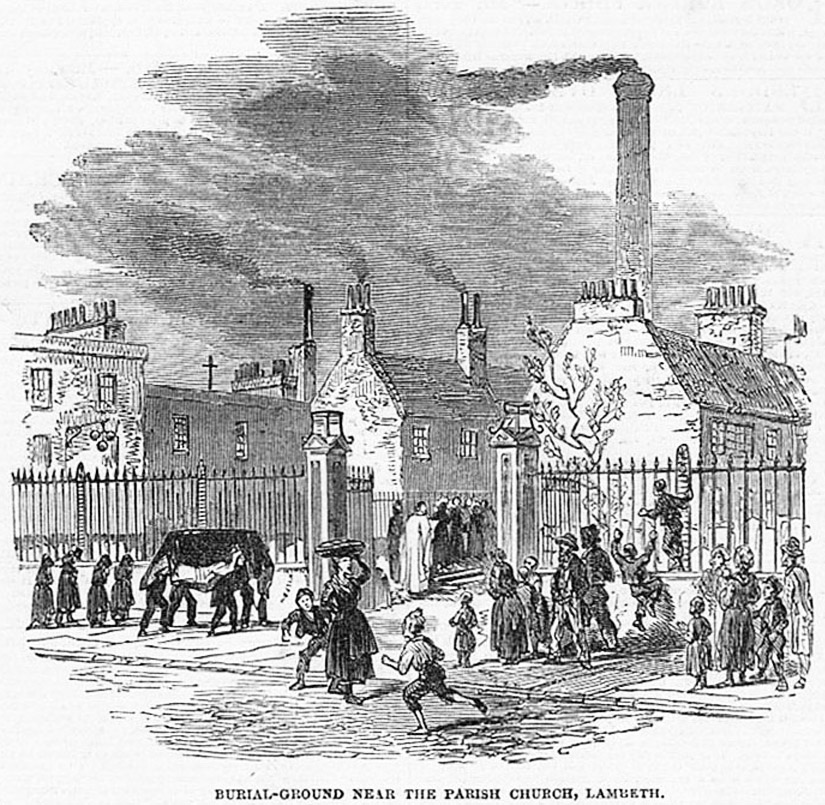

Below we see Lambeth burial ground on the High Street, pictured on 15 September 1849 in the Illustrated London News:

The mourners follow the coffin, the minister stands ready at the graveside, and the artist gives us some nice insight into Lambeth in the 1840s.

There's a whole lot of chimneys and a whole lot of pollution in view. The balls of a pawnbroker's shop-sign hang cheerlessly at the left of the picture; the artist is characterising the poverty of the area. Barefoot local kids clamber on the railings and play in the street around a street-hawker, who is yelling "get yer luvverly fresh bread 'ere" by the look of it. You can almost step though your computer screen and gaze up at the chill leaden London sky that hangs over the procession.

We are looking from the point of view of the orange arrow:

I strive to be chronological as I weave the threads of history into the Partleton Tree, but sometimes it just works better if I don't, so I'm going to flash back again briefly:

A few days after that body-snatching news-story on the High Street, in December 1817, we discover another case of of a person being laid to rest in the original graveyard in the grounds of St Mary's church:

xxxxxxx

xxxxxxx.jpg)

What we see above, atopped with a coadestone breadfruit, is the tomb of Captain William Bligh, of Mutiny on the Bounty fame, who died on 07 December 1817.

The reason he was interred in St Mary's churchyard - more than 100 years after it had been closed to burials in 1705 - is that the Blighs also had a family plot in the graveyard. Bligh - who was a very able mariner and who may not have been the harsh disciplinarian as portrayed in legend and movies - had been released by the mutineers in 1789 with 18 crew members. This tiny band navigated 3600 miles of ocean to safety in a microscopic 17-foot rowing boat, an extraordinary feat. After returning to Britain he continued to progress his career, eventually becoming vice-admiral. The epitaph on the tomb celebrates his battles but discreetly omits any mention of the, er, well, mmm, - cough - mutiny - don't say it too loud!

Appended to the back of the Lambeth burial register are two much later 19th-century burials, probably in the churchyard. Since they occurred after the 1852 Burial Act, they both required express permission from the Secretary of State. Whether or not this was actually sought, or achieved, by Lambeth parish, I have no way of telling, but my guess is that it probably was:

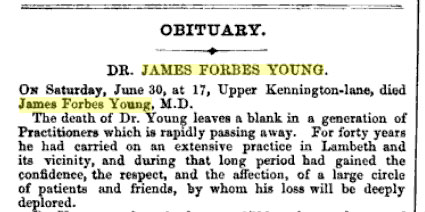

On 07 July 1860, James Forbes Young MD, circled in green above, was buried.

James, seen below, had been the Lambeth parish doctor for 40 years:

xxx

xxx Left: Medical Times & Gazette, 14 July 1860

Left: Medical Times & Gazette, 14 July 1860

That leaves just one more burial, fully 23 years later, when, in 1883, Elizabeth Squire Shewell, circled in purple, became the absolute last, final entry in the register of burials. And she also became definitely the very last person to be buried in the original metropolitan Lambeth parish.

Elizabeth, who had been born in Lambeth in humble circumstances, had become the very wealthy second-wife and widow of merchant Edward Shewell. She had previously been his servant - and was 38 years his junior. He died in 1838 and she outlived him by 45 years, leaving a fortune of £77,614 in her will. The fact that her body was brought 48 miles from her grand house in Lewes on the south coast suggests that she had come to Lambeth to be interred in another family plot.

St Mary-at-Lambeth church was deconsecrated in 1972, and is now the Garden Museum, but Bligh's tomb is still there:

The photograph of the Garden Museum above, with Bligh's tomb picked out by the yellow arrow, draws our attention to a few points of interest...

Those of our gentle readers who are very observant might have noticed that the present-day building in the photo above has completely changed since Buckler painted it in 1828, below left.

Our Victorian forebears weren't always particularly delicate when it came to preserving ancient architecture. The church was 'restored' in 1851, as we see it drawn by William Richardson on the right. This 'restoration' involved completely demolishing the old church with the exception of the tower, and rebuilding it from scratch.

xxx

xxx

Bligh's tomb can be seen in Richardson's drawing if you look carefully, but if you check the modern photographs of the Garden Museum, you'll see that the other small gravestones evident in the 19th-century pictures - those of the common people - have disappeared. Who removed them? Dunno, but I expect they didn't ask anyone's permission, and in fact, unless a plot was paid for in perpetuity - which is not usually the case in any burial, ancient or modern - the church didn't need any permission to re-use the land.

Our Charles Partleton was 9 years old when the church was rebuilt, and he was living just round the corner, as we shall see, so there's no doubt that he saw the demolition and rebuilding, though he may not have paid it much attention.

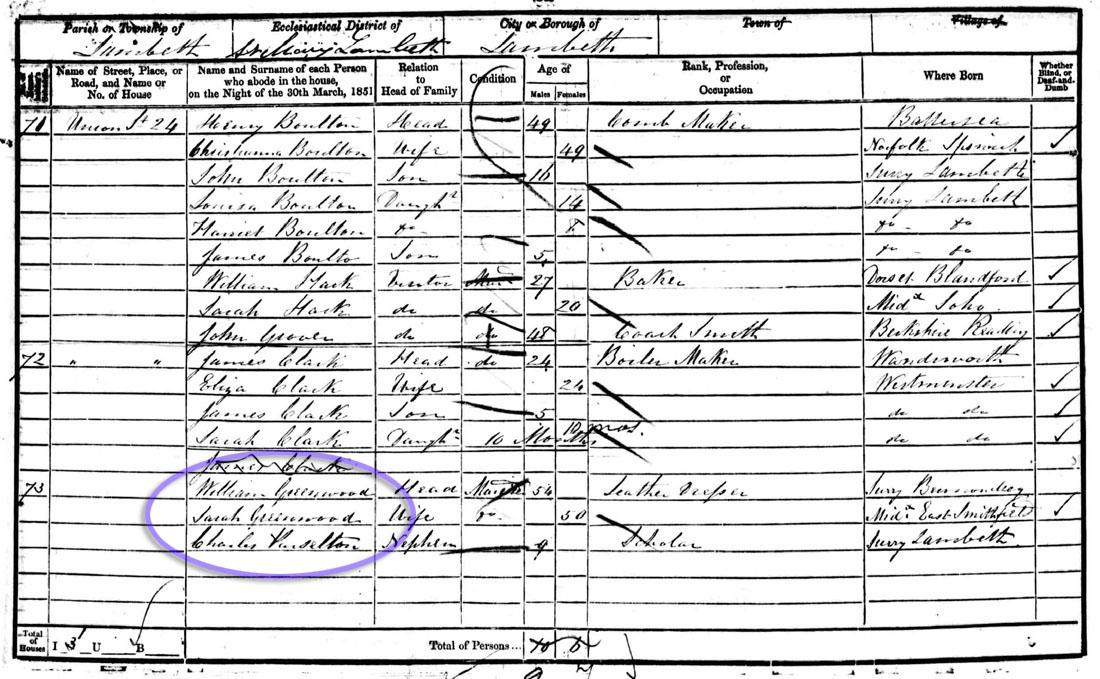

I think we've had enough of churches and burials. Let's get back to baby Charles, the subject of this page. The funeral of his father is over, and with no breadwinner, his mum Mary Greenwood will have no choice but to split the family up. So it is no surprise eight years later, in the 1851 census, to find nine-year-old Charles Partleton living with his uncle William Greenwood and his aunt Sarah Greenwood at 24 Union Street, Lambeth. In the census, Charles' surname is mis-spelled as Parselton:

This may have been a temporary stay, but I suspect not. Charles' mum Mary was, at this time, living a mile away, and scraping a subsistence income by taking in laundry. William and Sarah Greenwood were childless, and I'm going to take the view that Charles had effectively been adopted by them. The arrangement, in the context of the larger family, may of course have been more complicated than that.

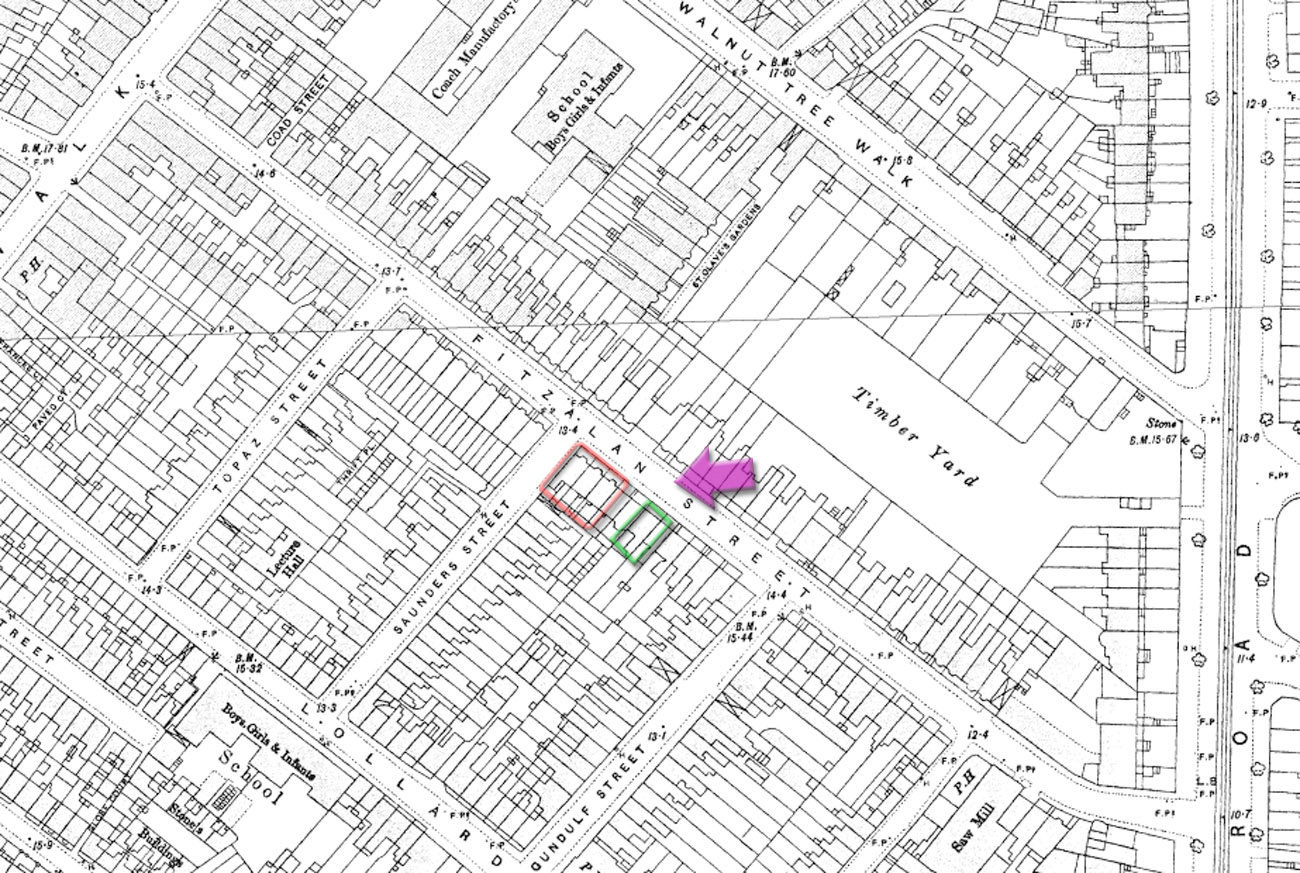

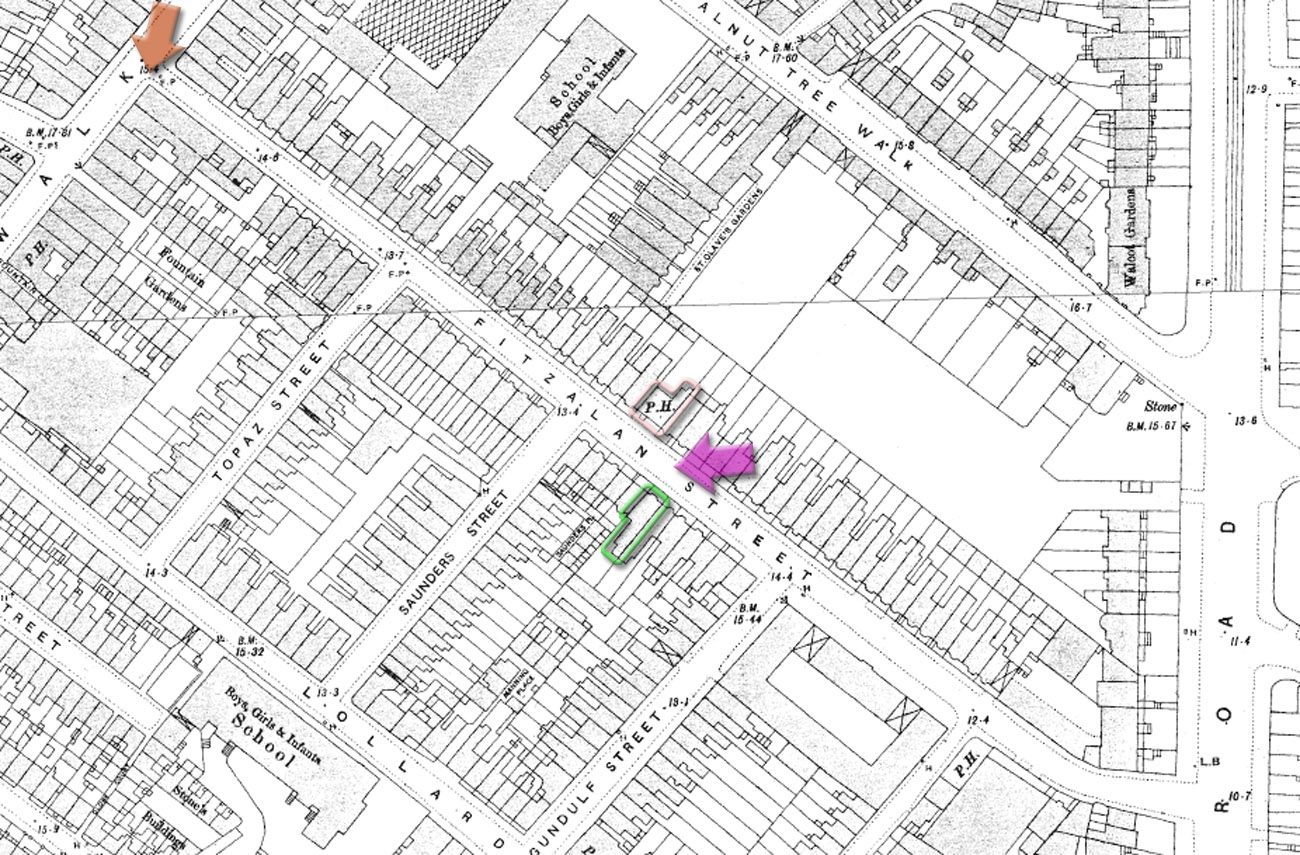

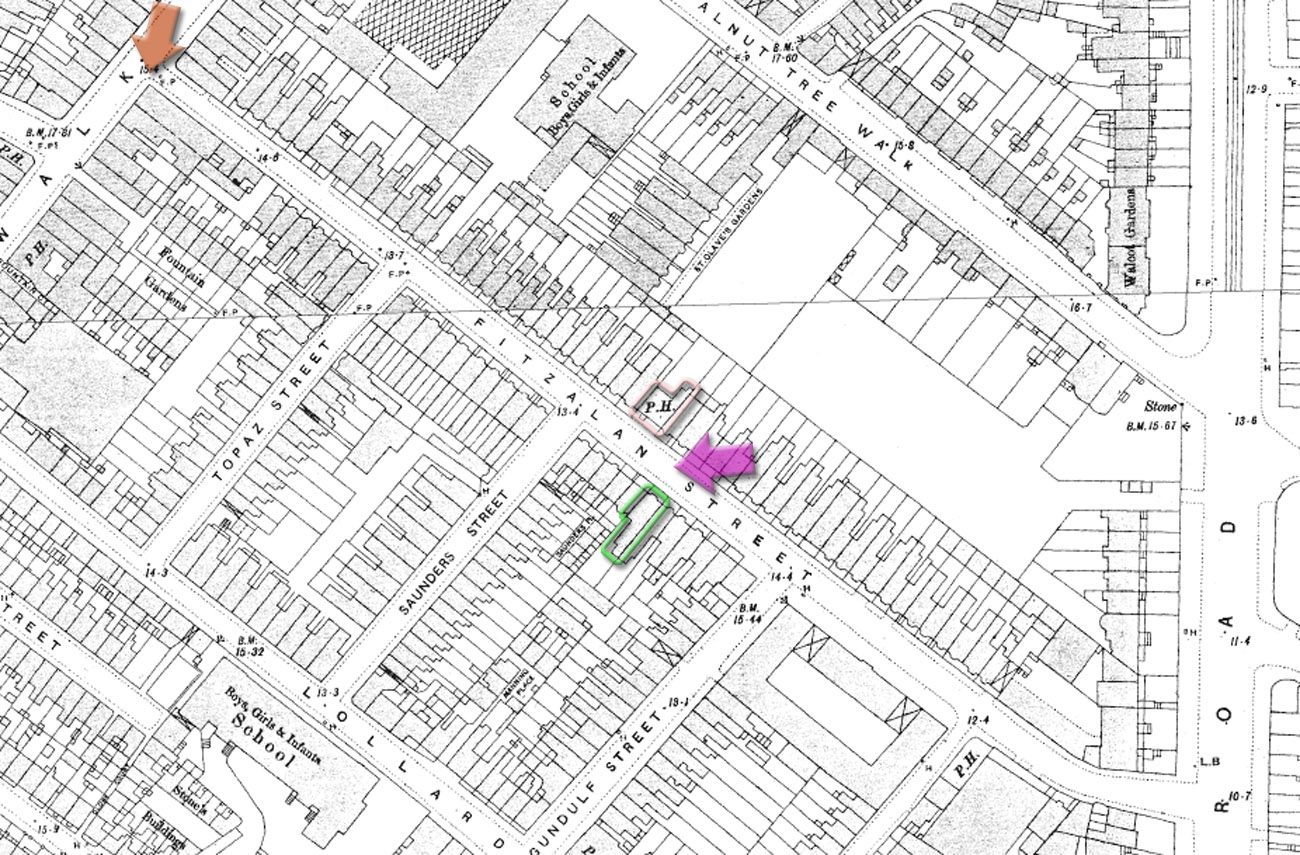

Union Street, where young Charles was living with his relatives, is circled in orange in the map below:

Again we can get a closer look, in Stanford's 1862 map of London. Union Street, a side-road off Lambeth Walk, is circled orange:

As luck would have it, number 24, the house where Charles was living during that 1851 census, is one of the few houses numbered on Union Street in Richard Horwood's 1799 map of London, the dwelling outlined in green below:

Of course, Charles and his uncle and aunt didn't occupy the whole house at No 24 - they shared it with two other families, and only have a single room.

And - as luck would have it - below, we do have a surviving photograph of this block of houses in 1972, before they were demolished, seen from the viewpoint of the purple arrow in the map above.

I have matched the house numbers to Horwood's map above.

24 Union Street, where my great-great-granddad Charles Partleton was living in 1851, is the location tantalisingly sliding out of picture at the left, and I make no excuses for getting a jeweller's eyepiece out and spending 5 minutes examining this photograph...

Below is a map of Union Street of 1876, with Charles' house, number 24, outlined in green. The 1972 photographer stood at the point of the purple arrow:

Union Street was renamed as Fitzalan Street in 1893, which is how we find it in the 1895 map we see below:

If we compare the two maps above - and I love comparing maps - we see that Charles' house was still there in 1895, outlined in green, but the three houses outlined in red, numbers 27, 28 and 29, on the corner with Saunders Street, have been knocked down and replaced with Victorian houses - the telltale clue is that the flat Georgian frontages are gone and the plan now shows bumps for their Victorian bay-windows, which are evident in the 1972 photo below:

And when we unfold a map of 1914, below, we find that Charles' house at number 24, outlined in green, has also been demolished, and has had a turn-of-the-century replacement which also features a bay-window. This is the building which is sliding out of view in the 1972 photo above:

So, that's not Charlie's bedroom in No 24 at the left of the picture below...

...and I'm pretty sure there wasn't a Morris Marina parked out front in 1851, but otherwise we may step into his 9-year-old's shoes and look at his next-door neighbour's surviving houses at number 25 and 26, which, of course, looked exactly like his house before its demolition.

In the 1970s, all these houses on the south side of the road were demolished, as we see in the 1980s photo below, and nicely replaced with a park, young trees all newly planted, which is called the Lambeth Walk Open Space, like a breath of air, restoring a small piece of Lambeth to how it looked before it had been completely paved over:

In the 2012 image we see below, the little saplings have become mature trees and the former location of Charles Partleton's 1851 house is at the point of the green arrow:

Not many old buildings are preserved around this part of Lambeth, but, almost directly opposite Charles' house, at the point of the pink arrow in the image above, there is a surviving pub which was there in 1851 - the Royal Oak, which our Charles would recognise:

The publican of the Royal Oak in the 1851 census was Irishman Hugh Cavanagh. If Charles' uncle William liked a pint, he would have known Hugh.

The pub must feel a bit lonely as all of its neighbours have been demolished over the years. The past - and present - location of the Royal Oak, 78 Union/Fitzalan Street, is outlined in pink in the map below:

Before we leave Union Street, I'd like to take a quick stroll with Charles to the end of the road where he lived, to Lambeth Walk, from the viewpoint of the brown arrow in the map above:

xxxx

xxxx

Taylor's large draper's shop at the corner of Union Street and Lambeth Walk was established in the 1840s, so - take away the 1950s shop-front and other later-Victorian modifications - as we see on the right, and our Charles would know the older parts of this landmark at the end of his street very well. Taylor's buildings were demolished in the late 1960s.

The photograph above, which is an interesting snapshot-in-time in its own right, was taken in 1960 from the viewpoint of the brown arrow in the map below:

Lambeth Walk, a street-market made famous in the 20th century by the song of that name, is covered in some depth in its own page in The Partleton Tree, but since it must have been extremely familiar to Charles Partleton, we should take a quick glimpse of what it looked like:

The photograph above was taken as late as 1973, but I think it gives us a fair visualisation of how it looked to Charles 122 years earlier.

And here's a final glance back at the graveyard at St-Mary-at-Lambeth church, from the viewpoint of the red arrow in the map above, in this c1860 photograph of the cemetery gates taken by photographer William Strudwick:

"So, little Charlie was being raised by his uncle and aunt at Union Street... but where was his mum, Mary, in the 1851 census?", I hear you cry.

That's a good question, and after much searching, I finally found her along with Charles' 14-year-old brother Joseph:

Ancestry.co.uk had Mary indexed as Mary Castleton, which is understandable when you look at the handwriting in the census form. I can tell you that name took some finding due to Ancestry's limited wildcard search facility.

In the census we see that Mary was taking in laundry, a Victorian occupation which yielded notoriously meagre earnings. She was residing with Charles' older brother Joseph in a single room in Marshall Street, between the Elephant & Castle and St George's Circus, in the green circle in the map below. This was a mile or so from Charles, in the orange circle:

And this page is getting rather long, so it seems a good place to break off with a new page, wherein we will see some great pictures of Lambeth, including a house where Charles lived.

But that's Part II of this history, and a story for another day.

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... or would you like to discuss any of the history... or if you have any observations or comments... all information is always welcome so why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'In Their Shoes' Page.