Benjamin Charles Partleton (1824-1884)

Part I

The official record of the formal events of the life of Benjamin Charles Partleton is full of enigmatic gaps, missing certificates and unidentifiable offspring.

He was born in Lambeth, as is often the case on this website, so, as usual, let's establish where exactly Lambeth lies in relation to London:

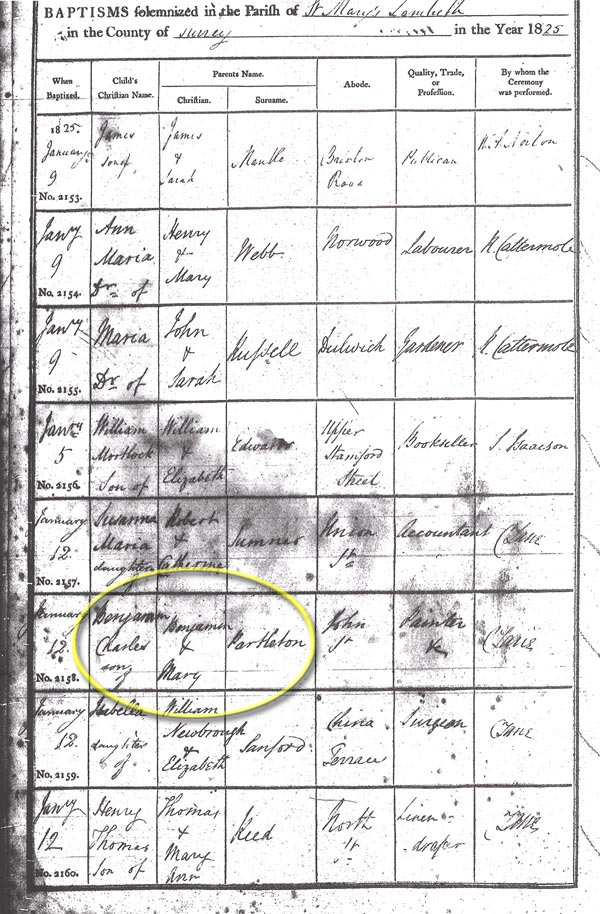

We don't know Benjamin's exact birth date, but it was probably during the year 1824. Here's his baptism on 12 January 1825 at St Mary-at-Lambeth Church, circled in yellow below.

St Mary-at-Lambeth church, where the baptism took place, is circled in blue in the map below:

Benjamin's birthplace in the parish register of 1824 - John Street - is at the point of the red arrow in the map above.

What kind of palatial residence was John Street? Well, someone was kind enough to photograph it, from the point of view of that red arrow, so let's have a look:

In the photograph above, we can step into little Benjamin's baby booties as his mum wheels him down the road in a pram. Actually prams would not be invented for another 15 years, and when they did come, they were for rich folk. So Benjamin's mum carried him in her arms. Anyhoo, John Street is the road branching off to the right. The prominent TV aerial on the chimney-stack gives us the clue that this photo was taken in 1960 not 1824, and the mess of adverts for Tizer, John Player's cigarettes etc, splattered on the walls of the corner-shop are of a 20th-century flavour, but of course, everything else is unchanged from when Benjamin Partleton lived on the street.

We can visualise the day of the baptism for Benjamin's young parents Benjamin Thomas Partleton (1799-1843) and Mary Ann Greenwood (1800-1855)...

The map below is Richard Horwood's map of London in a c1803 revision, and we see the beginnings of John Street circled in red:

Their journey, on that distant Wednesday morning, from home in the red circle, to the church in the blue circle, took Benjamin and Mary with baby Benjamin past a large windmill - named as such in the green circle in Richard Horwood's map.

The painting we see below was created by artist Henry Pyall in 1820. We see the windmill, just as Benjamin did, from the green arrow in the map above, and in the distance we St Mary-at-Lambeth church where he was baptised:

And arriving at the church, looking back towards their home from the direction of the blue arrow, conversely, look carefully and you'll see the same windmill in the distance:

Benjamin lived his adult life in the reign of Queen Victoria. But when he was born, the King was George IV, so let's have a quick look at him.

Below we see the handsome young man, before he became king, depicted by illustrator James Gillray:

James Gillray doesn't pull any punches in the above - notoriously cruel - depiction, which I have left at full resolution for the pleasure of the gentle reader. Prince George is shown busting every seam of his attire, picking at his teeth with a laconic expression on his face. He is surrounded by signs of the excesses for which he was famous; unpaid bills; empty booze bottles; pile ointment; 'drops for the stinking breath'; and gambling paraphernalia on the floor.

George had been Prince Regent between 1811-1820 during the madness of his father George III, and was king from 1820 to 1830. John Street - Benjamin Partleton's birthplace - was started in the early 1800s and finished some years later, so the house where Benjamin was born would be Late Georgian, or perhaps more specifically Regency, as are many surviving houses in the surrounding area of Kennington. That makes it sound posh, which, as we saw in the photo earlier, it certainly wasn't.

George IV was a patron of the arts, and his reign - whatever his personal faults - is known for its outpouring of creativity in the arts and architecture. Benjamin Partleton grew up in a liberal country, where subversive illustrations of the prince, such as we see here, were possible. The one below of George as Prince Regent, making him look ridiculous, is by the genius George Cruikshank:

George was an unpopular king, always under the influence of his favourites. He passed away in 1830, and when he died, The Times didn't pull its punches either:

Left: The Times, 29 June 1830

Left: The Times, 29 June 1830

So, let's get back to our Benjamin. He had an older sister, Mary Catherine, who had died before he was born, and thus he was the eldest child, and was to have seven other brothers and sisters, the youngest of whom was my great great granddad.

Benjamin grew up in Lambeth except for a short move, c1827, to Stratford in the East End of London when he was a baby.

The next we see of Benjamin is the 1841 census; circled in blue. He's now a young man of 16:

Above we see that Benjamin's dad is a house painter, and that young Benjamin himself is a 'leather dresser' - a tanner. He had learned this trade from his mum's family, the Greenwoods - his uncles ran a leather-tanning business - though he may not have thanked them much for it because is it a notoriously messy smelly job.

So far, so good, but from here on we need to put on our Sherlock Holmes hat and pipe because Ben is not going to make it easy for us.

Benjamin never married - at least, we can't find any official record of a wedding, which is quire unusual - but it appears that at some time in the 1840s, he paired up permanently with Harriet (aka Louisa) Tems.

Ok, let's move on to the year 1848 and the next thing on the record, a certificate uncovered by Terry Partleton.

Above we see that Benjamin and Harriet were living in Lambeth and had a daughter, Louisa Harriet Partleton. The spelling of the maiden name of Benjamin's wife is hard to discern but it looks like Tems. Though the parents apparently aren't formally married, Harriet has clearly taken her partner's surname of Partleton

Benjamin had given up leather-dressing and had become a house painter like his dad - maybe he didn't like the stink of the tannery. He and Harriet were residing in 1848 at 13 Richmond Street, which we see circled in pink in the map below; it's only 100 yards as the crow flies, from John Street where he was born 25 years earlier, at the red arrow:

So let's have a look at Benjamin's neighbourhood... below we see Hercules Buildings, seen from the viewpoint of the orange arrow in the map above.

In 1848, when the baby was born, the railway arches were brand new:

A little further west, we see the Lambeth Parochial School at Union Place, captured by artist Gideon Yates in 1825; this picture was painted before the railway bridge was built practically on top of the school. Lessons must have become noisier after that:

The painting above was executed in 1825 by artist Gideon Yates from the viewpoint of the purple arrow in the map below:

And proceeding further west, painted again by Gideon Yates, from the viewpoint of the pale blue arrow, we see the next house along, which is the rectory for St Mary-at-Lambeth church; firstly the outside view (1825) and then the inside (1917):

We move on, and we come across a poignant event, and a common - and shocking - experience for a working-class family during this era; the death of a little child.

After a fortnight's illness, Benjamin's daughter, little Louisa Harriet Partleton died of pneumonia aged just two years and four months:

During the baby's lifetime, the family had moved from 13 Richmond Street to 36 Richmond Street.

The date of Louisa's death was 11 March 1851. This was just 19 days before the census of England and Wales which took place on 30 March 1851.

So the obvious thing to do is to look at 36 Richmond Street in the census:

Benjamin is nowhere in the 1851 census, which is a puzzle. It is possible that he did some military service and was abroad; we'll see more clues later... but what about Harriet? Could that be her, circled in blue, at 36 Richmond Street? Harriet was illiterate - she previously signed her baby's death certificate with a cross - so we shouldn't be too surprised that the enumerator, who took her details on her behalf, wrote Thames instead of Tems. Her age and place of birth don't match other records at all well, but I believe it's our Harriet.

There are no records for this unmarried couple during the 1850s...

So we have to move on fully 10 years to the 1861 census:

Ok, the first thing we have to deal with is that Benjamin's wife is now recorded as Louisa, not Harriet. Terry Partleton & I had a chat about this and we're agreed that both of these forenames represent the same woman. You will recall that the baby who died in 1851 was called Louisa Harriet; again, too much of a coincidence. It seems that Benjamin's wife Harriet prefers to use the name Louisa from now on - and may have always used this name informally.

In addition, we see that Louisa's place of birth is difficult to read. It looks like 'Kent, Bonney'. This becomes clearer in later censuses.

Also, we have our one-and-only sighting of their 'son' William Partleton, who is 15 in the census and therefore must have been born circa 1846, also - apparently - at 'Bonney', courtesy of two ditto's. There is no birth record for William; he's also not in the 1851 census of ten years earlier, and subsequently has no census records or marriage or death certificate. He's probably adopted. The elusive William works in a pottery.

Benjamin, Louisa and William were Living at 3 Binfield Place, circled in blue in the map below, which is at 258 Clapham Road. It's a mile or two south of the usual Lambeth locations we are accustomed to seeing. In fact this exact spot will become world-famous in the year 2005.

Comparison with the 2008 map above shows us that Binfield Place of 1861 is, 30 years later, to become the location of Stockwell Underground station in 1890, which is great news for us because we will have lots of pictures to look at.

The pictures come from the London Transport Museum, and we are to thank them for having created a time machine! Sit down at the machine, scroll through the photos and watch the changes through the years!

In the picture below, of the year 1890, we see the brand new Stockwell Underground Station, and next to it, indicated by the yellow arrow, we can see what Benjamin's residence looked like, because it is what remains of Binfield Place. Part of it has been demolished to make way for the station, including, I believe, the room in which Benjamin stayed:

04 November 1890; the grand opening of Stockwell Underground Station by the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII). Check the line of soldiers with tall hats in the foreground!:

1912; the frontage of the station is extended to the main road. Binfield Place, behind the station, is now a bank and has also had a frontage of grand pillars added for bank-style gravity:

Below: December 1924. Due to line expansion, the whole station shebang has been knocked down and replaced with an art-deco-style building. The dome, whose function had been to disguise the lift winching gear, is no longer needed because escalators have been installed.

Binfield Place is unchanged in the background:

1925; we clearly see Binfield Place as Barclays Bank:

1933; The original 'Underground' sign has been replaced by the familiar London Transport roundel:

1955, austerity; the station is looking a bit sorry for itself. For some reason the 'Underground' sign has been removed:

1962; A sunny day and Binfield Place is still there as Barclays Bank:

Below: 1974... whoops, what's happened! Under the ground, the Victoria Line has come, and as a consequence, the station had to be expanded and rebuilt in 1971. The architecture we see below is very much of its time, and actually it's growing on me. The tall bit is a ventilation shaft.

The station has been extended to the left, and as a consequence, Binfield Place has been wholly demolished. There are 1960s blocks of flats behind the station. The bollard at the corner of the road on the right of the picture is a survivor visible the 1912, 1925 and 1933 photos:

2001: a second floor has been added to the station. The block of flats in the distance is getting a facelift - or is it being demolished?:

And here's a view of the junction in 2012, courtesy of Google Street View:

Ok, that's the end of the time travel experiment, but before we move on, the name 'Stockwell Tube Station' may be ringing a bell in your memory...

On 22 July 2005, Jean Charles de Menezes, a Brazilian electrician working in London, entered Stockwell Station at 10:01 a.m., on his way to a job. He is labelled "JC" in the above security picture. Jean Charles is not wearing "bulky clothes" or a carrying a rucksack as was later claimed. Nor did he jump the barriers.

In the next picture, 40 seconds later, we see that he is being followed by two undercover police officers "Ivor" and "Ken".

The previous day, 21 July 2005, there had been four attempted bombings in London on the Tube and on a bus. Police officers, acting on a lead and in a hurry, had mistaken Jean's identity for a suspect in the bombings.

Unfortunately for Jean, there was a train standing at the platform, just about to depart, and he made a run for it - as we all do - and the police interpreted this action as suspicious. Shortly after boarding the train, while it was still at the station, Jean Charles was pinned down and shot at least five times through the head. He was innocent of any connection to terrorism.

This is a family tree website, but I could hardly avoid mentioning the above incident. It was later covered up and whitewashed; the Metropolitan Police were fined a mere 175,000 pounds. It is possible that the killing was not carried out by the Metropolitan Police, but by Special Forces.

Deep breath, let's wind the clock back to 1861 and get back to our Benjamin who is living at the exact place where Jean Charles is to die 144 years later, Binfield Place:

Below we see Clapham Road, the section of street which includes Binfield Place, from the point of view of the red arrow in the map.

And the same view in about 1930:

And again from the opposite direction, from the green arrow:

These pictures are from much later, from the 20th century, and contain anachronistic objects such as the large white War Memorial, but I believe they give us a fair flavour of what Clapham Road looked like, as does the picture below of c1910, looking south-east down Binfield Road from the orange arrow:

So many photographs. But now we can really put ourselves in Benjamin's shoes. Notice in the map below that directly opposite his house there is a pub, the Swan Tavern, circled in purple:

Here's a photo of The Swan taken by William Strudwick on 25 March 1866, from the viewpoint of the purple arrow... step into his Benjamin's muddy shoes as he steps out of his front door on to the dusty main road:

Thanks again for the above picture go to William Strudwick, who took fabulous photos of Lambeth in the 1860s.

Here's how the view looks today:

It's still The Swan, but the pub was obviously demolished and rebuilt in the 1920s/30s. It's amazing how things get knocked down in London! But if you look carefully, you'll see four of the five Georgian terraces in the adjacent building are still there, just exactly as they were in 1861.

The Swan evolved through at least four versions; the buildings being demolished and rebuilt in turn. The one in the image below, by artist 'CM', was there before Benjamin lived at Binfield Place, at a time before London had fully expanded its reach into the countryside at Stockwell. I'd date the engraving to about 1840-1850. George Wardell, named on the pub sign, was publican of the Swan in the 1841 and 1851 censuses. He died in 1860:

And finally, here's how The Swan looked in 1780...

Mmmm... all things must change, and it's pointless romanticising some long-past era, but, it's clear to see that there had been a massive impact on the landscape.

Benjamin is about to move to the edge of the countryside, and he will witness this change first hand in Part II of his story.

Click here to continue with Part II of Benjamin's story, wherein we will see some great pictures of the changes which occurred in the countryside around London in the 1800s.

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... or would you like to discuss any of the history... or if you have any observations or comments... all information is always welcome so why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'In Their Shoes' Page.