Benjamin Thomas Partleton (1799-1843) in 1841

Benjamin Thomas Partleton (1799-1843) is of particular interest to the creator of this web page because he is my great-great-great granddad. Click here and use the ‘Search’ button in the PDF document if you'd like to remind yourself where Benjamin sits in the tree.

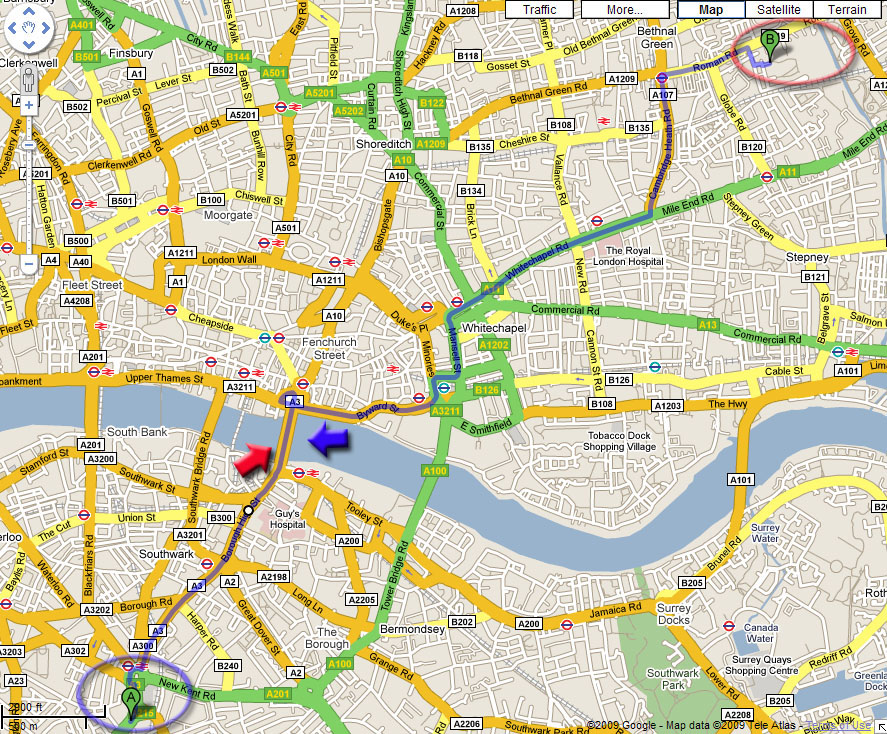

Benjamin grew up on Swallow Street, in London in the parish of St James, circled in green in the map below.

Here he was christened on 15 July 1799 at St James Church Westminster, alternatively known as St James Piccadilly.

Below is how St James Piccadilly looks today. Note the street name in the photo - Swallow Street - which is where Benjamin grew up in the early 1800s.

Benjamin’s father is also named as Benjamin in the register; his mother's name is given as Catherine, and we know that she was born Catherine Iremonger.

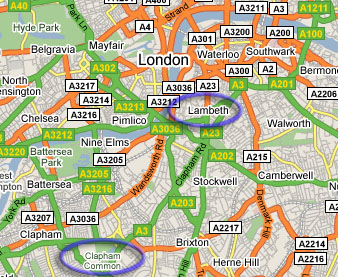

In 1815, our Benjamin moves south of the river to the poorer area of Lambeth - distinctly a move down-market, caused by the compulsory purchase of his house on Swallow Street to make way for Regent Street. Below we see the location of Lambeth, circled in yellow:

Benjamin's wedding is the first reference to a Partleton south of the river - the first of many. He married Mary Greenwood in the church of St Mary-at-Lambeth. You'll find dozens of references to this riverside church in these Partleton Tree web pages.

Here is the entry in St Mary-at-Lambeth's parish register for Benjamin and Mary's marriage; 29 July 1822 (a Monday):

Benjamin's dad has signed as a witness, a little creakily. Benjamin Jr, Mary and Eliza Greenwood have also signed in their charming hand. Literacy was far from universal as can be seen by the entry above them, signed with crosses.

So, let's try as best we can to step into Benjamin's shoes on the big day. Presumably they are his best shoes all polished-up. We can't do miracles here, but we can show a wedding at St Mary-at-Lambeth circa 1812-1820. In this case it is the wedding of two strangers, 'Randolph and Hilda', drawn by the famous caricaturist George Cruickshank. Since this is not a comic cartoon, we may presume that the bride and groom must be friends of George.

That's the Church on the right and Lambeth Palace straight ahead, a boat on the Thames behind them:

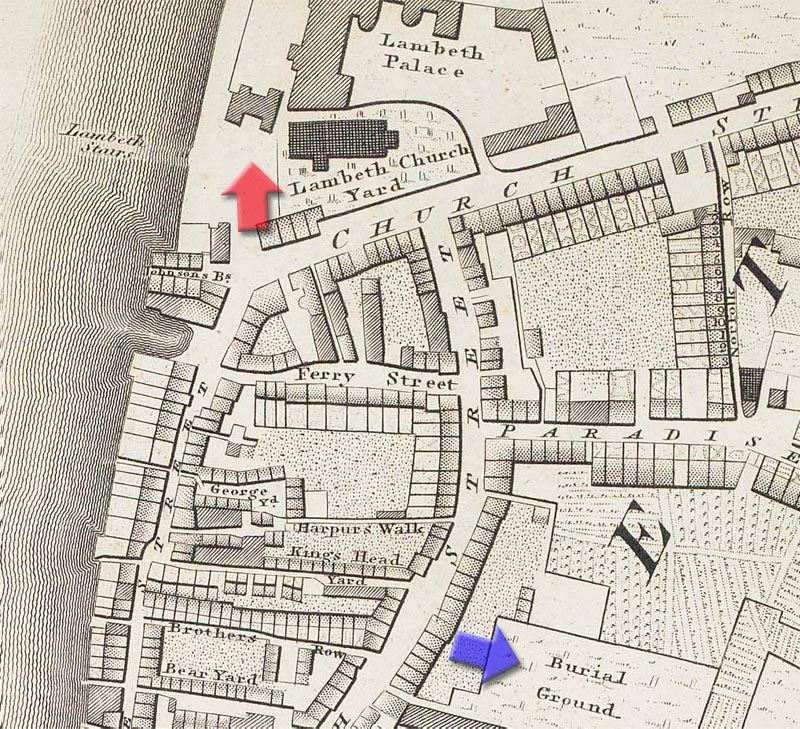

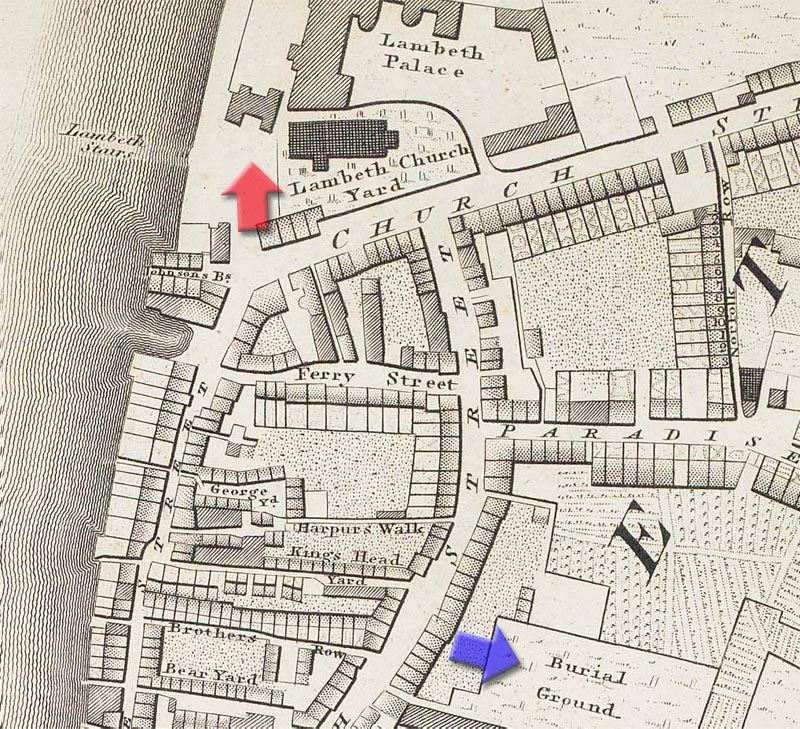

I think it gives us a flavour. The picture is drawn from the viewpoint of the red arrow in the map below:

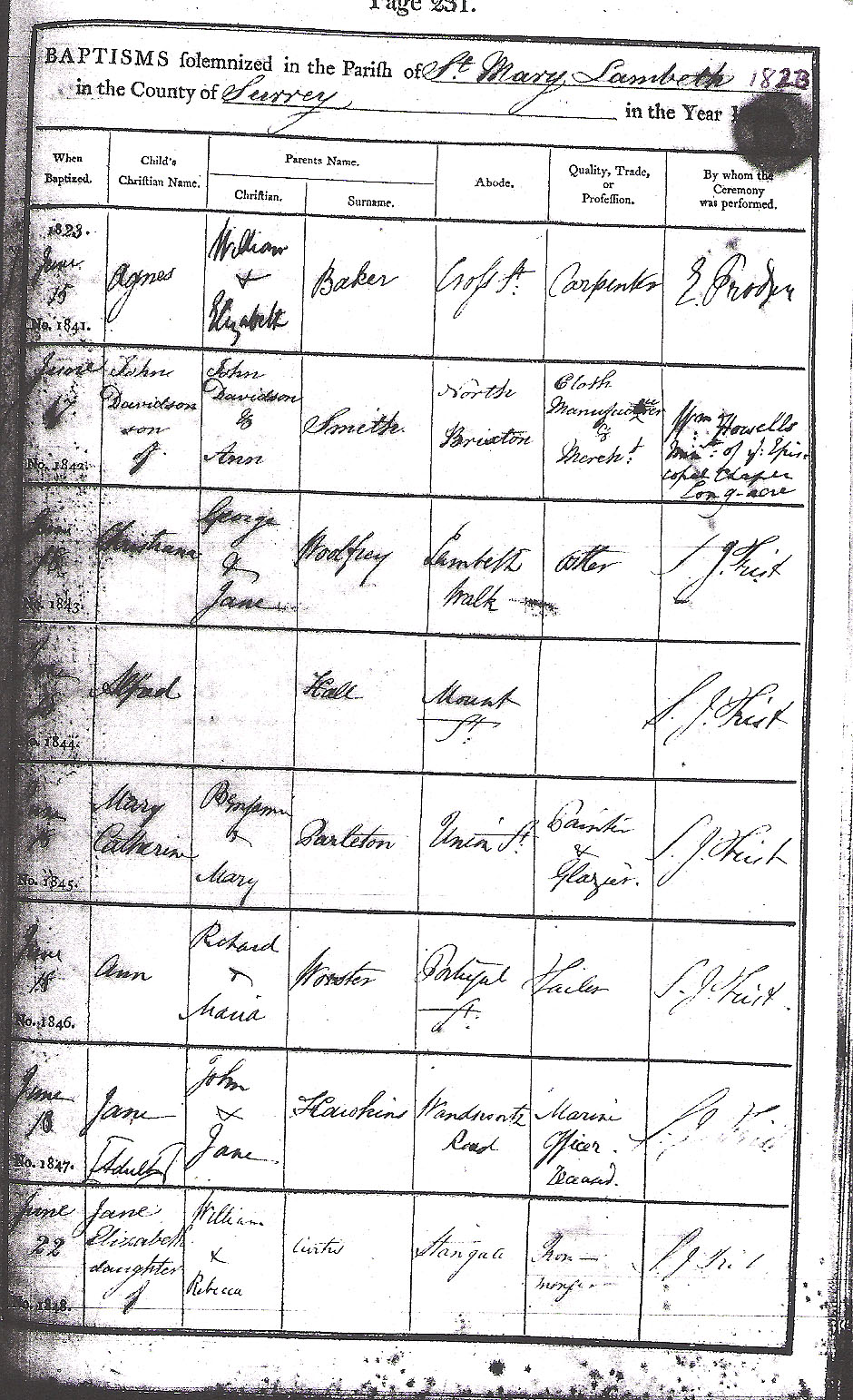

A year later, in 1823, Benjamin and Mary's first child was born; Mary Catherine. She gets her mother's name for her first name and her grandmother's for her second. She was christened on 18 June 1823 at St Mary-at-Lambeth:

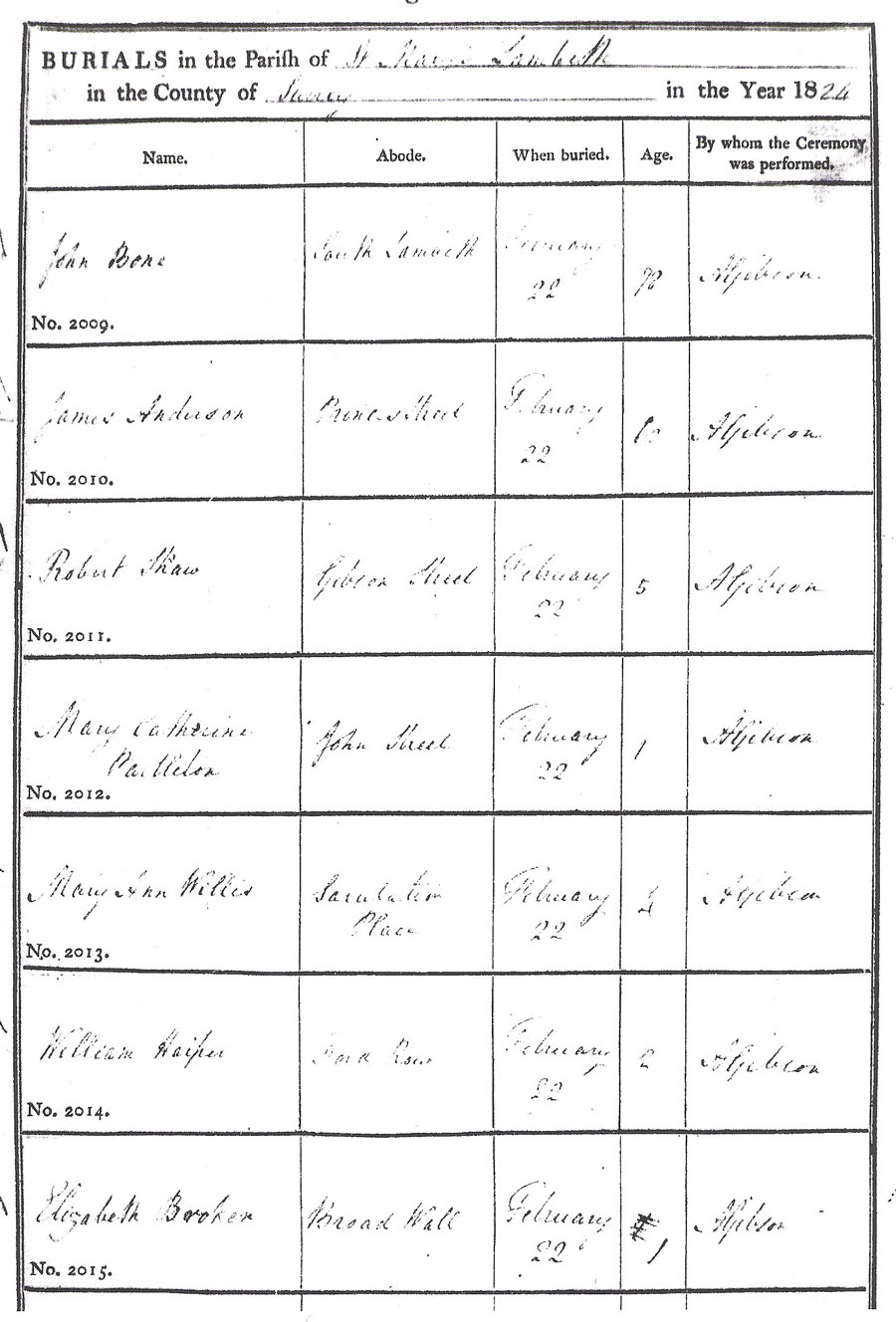

But tragically, little Mary did not live to see her first birthday. She died in 1824 and was buried on 22 February in Lambeth burial ground on the High Street, along with four other little children in that era of high infant mortality:

The burial ground is shown by the blue arrow in the map below:

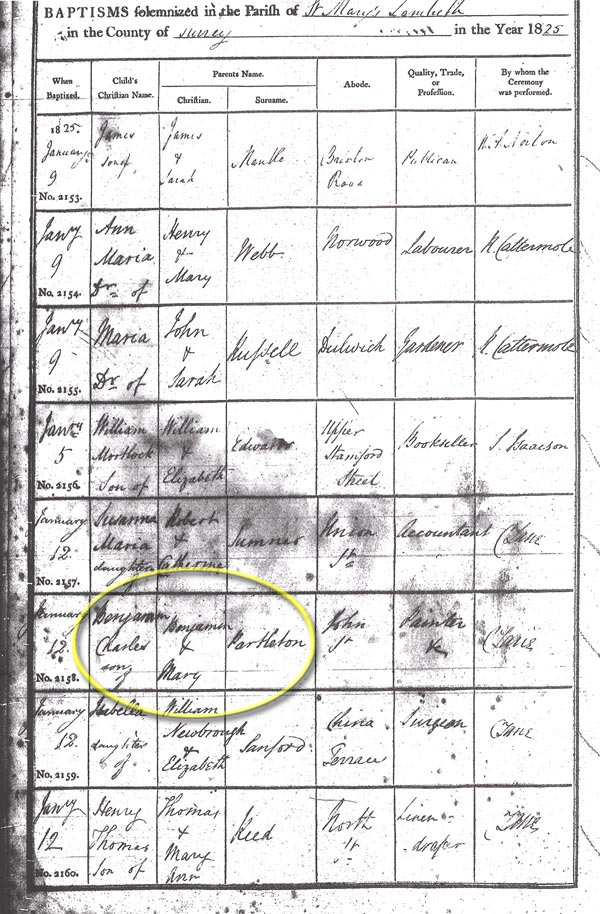

A year later, on 12 January 1825, Benjamin's first son is baptised; Benjamin Charles Partleton (1825-1884). Here is his entry in the baptismal register:

Benjamin Partleton (1799-1843) was a house painter like his dad Benjamin Partleton (1774-1833) - a theme which runs though male Partletons in the Lambeth area for more than a century. The family at that time lived in John Street seen on the map below:

In 1827, the family are not in Lambeth, but are in Stratford, East London. Why they went there, we don't know, but we do know they were there, because Benjamin's second son, William George Partleton, was born in Stratford in 1827.

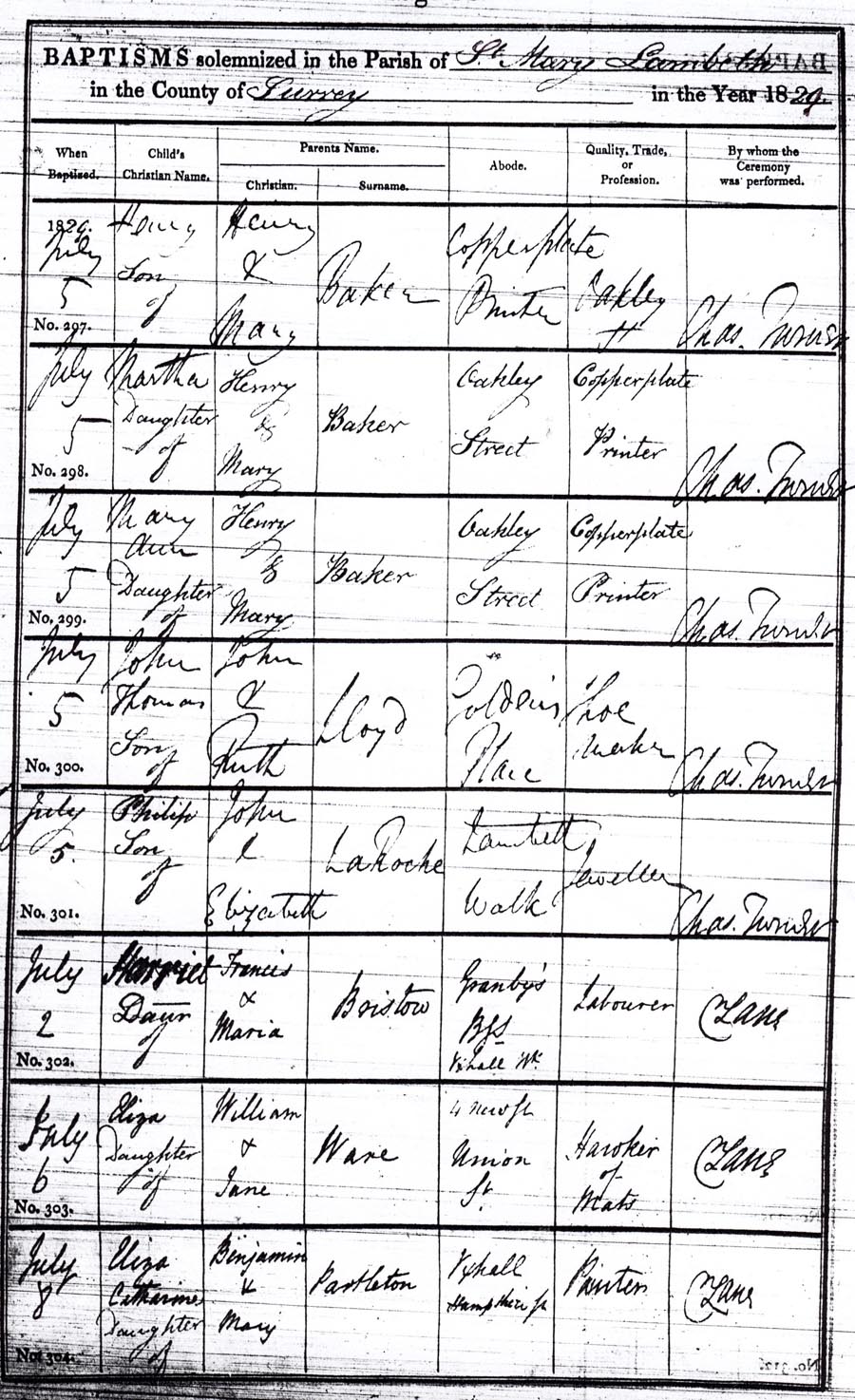

By 1829, Benjamin and Mary are back in Lambeth, at the Vauxhall end, where their daughter Eliza Catherine was christened on 08 July:

Eliza's birthplace is in Hampshire Street, which is the unnamed dotted street circled in red in the map below:

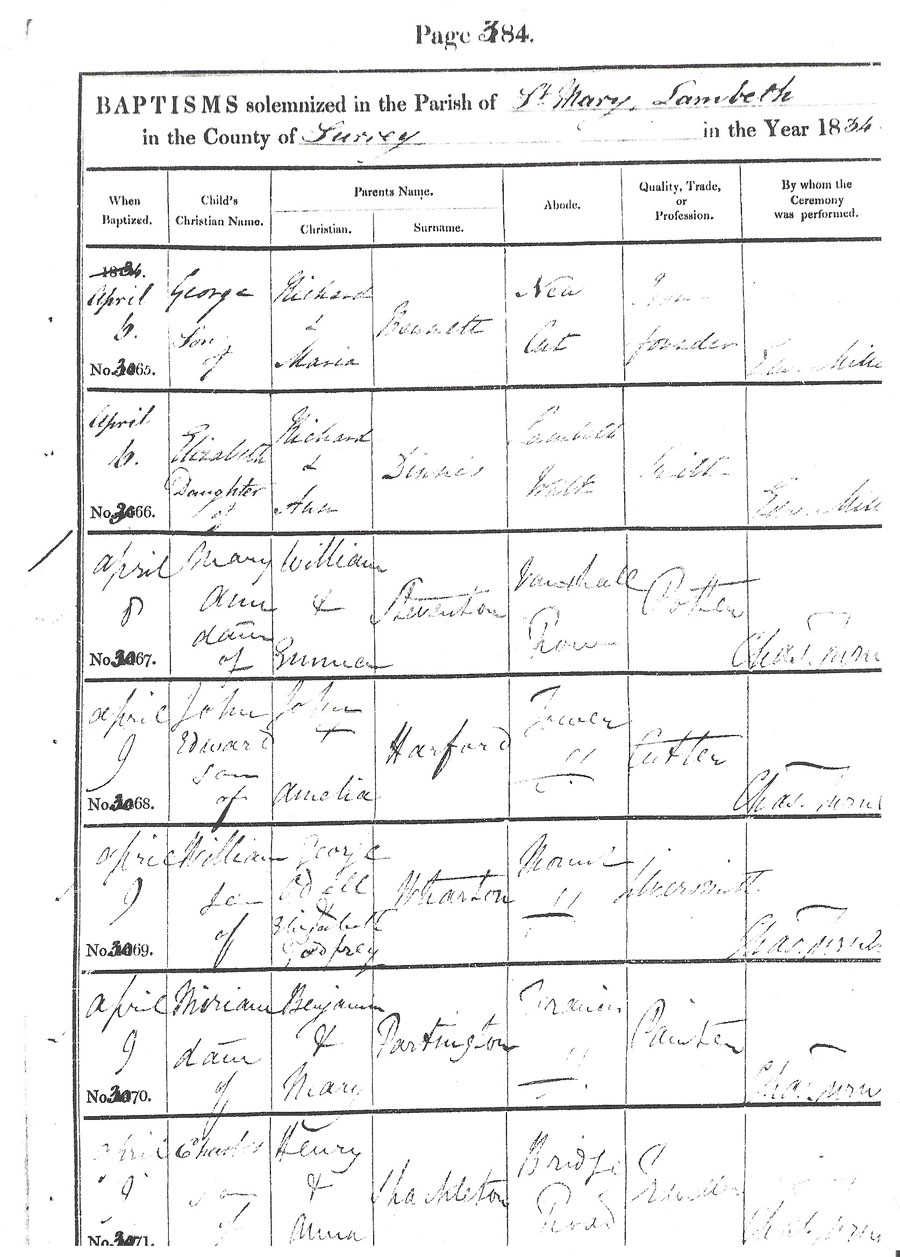

The next child we see is Marion Partleton who was born in 1834. Note her surname mis-recorded as Partington; not the first time - nor the last - that officials will make this mistake:

Marion's first name is also mis-spelled, as Miriam. Perhaps the vicar was a little deaf.

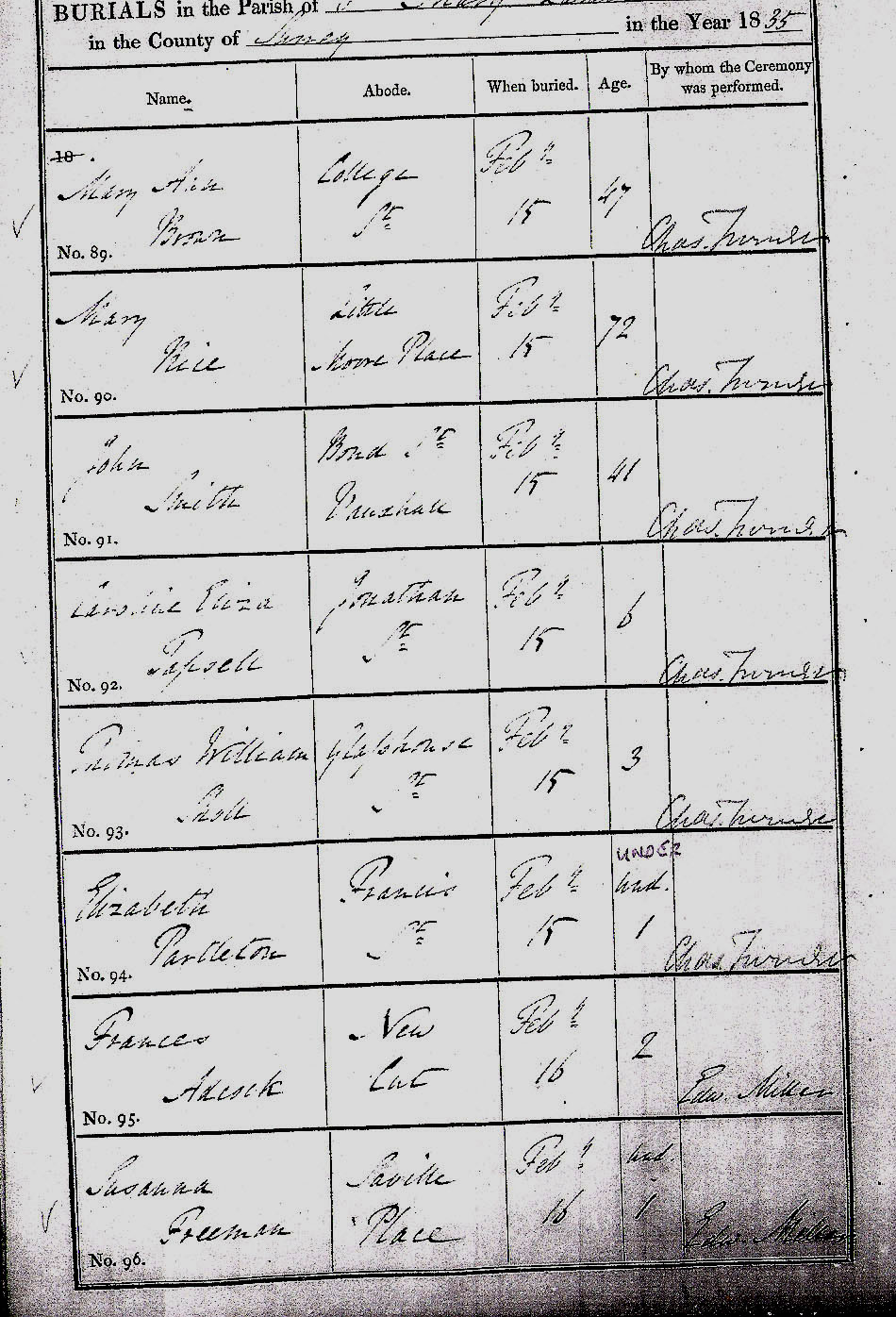

In 1835, Benjamin and Mary have another daughter. They name her Elizabeth in spite of the fact that they already have a daughter called Eliza!

What's the 'P' annotated in the margin of Elizabeth's entry? ... we'll find the clue to that later.

The family is now at Francis Street, circled in the map below. Barrett Street is also mentioned, which is at the west side of Francis Street, so the house must be on the corner, or near it:

Perhaps that 'P' annotation in her christening record signified that baby Elizabeth was very ill because, just a fortnight later, she was interred at Lambeth burial ground:

Indeed, it turns out that the 'P' in the baptism register is a very bad sign. I looked through the whole register; nearly all the babies marked with a 'P' died within a year.

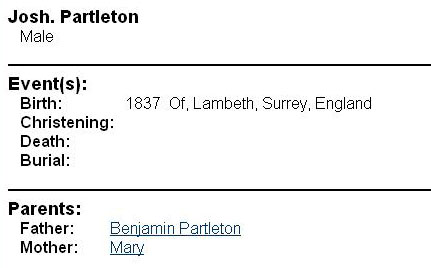

The babies keep coming. In 1837, Joseph is born:

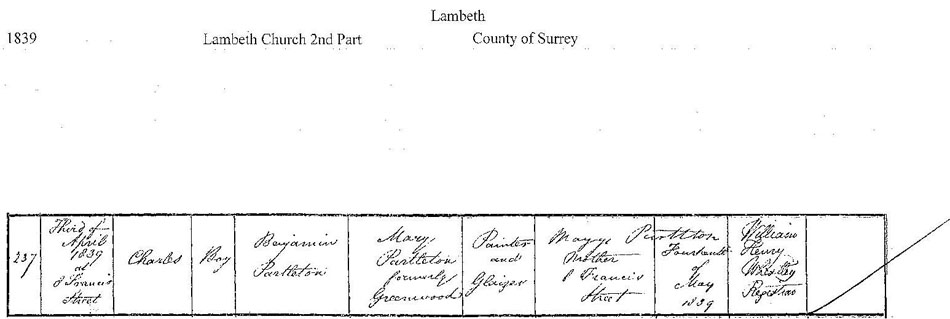

By 1839 Benjamin and Mary have had seven children, five of whom are alive. On 03 April their eighth child is born; Charles:

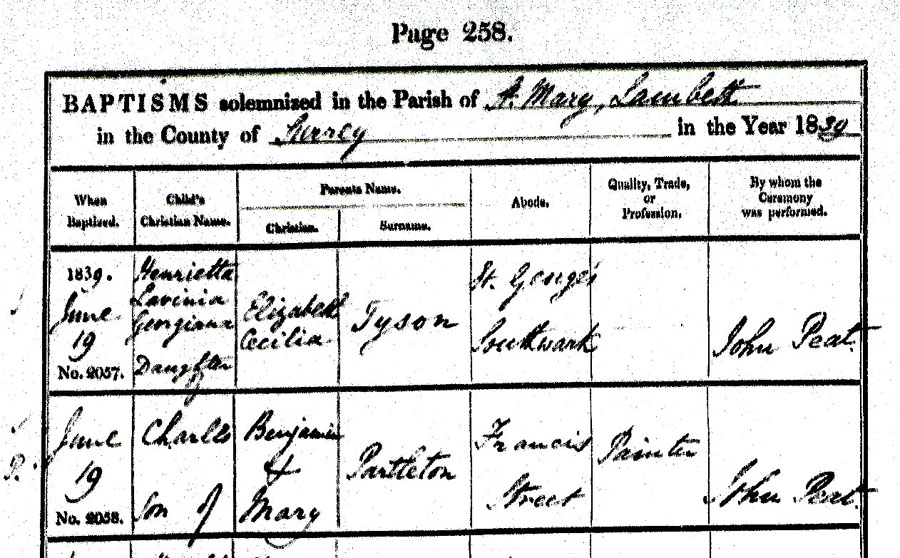

Charles is another infant mortality. He was christened on 19 June, with some urgency:

Charles has the dreaded mark of 'P' against his baptism. In fact he died on the same day he was baptised.

Below we see the death certificate:

Sarah Brook, the informant present at the death, was the Partleton's neighbour. She was a policeman's wife who can be found living at 4 Francis Street in the 1841 census.

Finally, after all these births, we see the whole family together. In the first full census in Britain, 1841, we find Benjamin living with his family at 8 Francis Street.

The census took place on the evening of 06 June 1841. We see Benjamin with his wife Mary Greenwood (1799-1856) and their children Benjamin 16 (A leather dresser), William 14, Eliza 12, Marion 8, and Joseph 4.

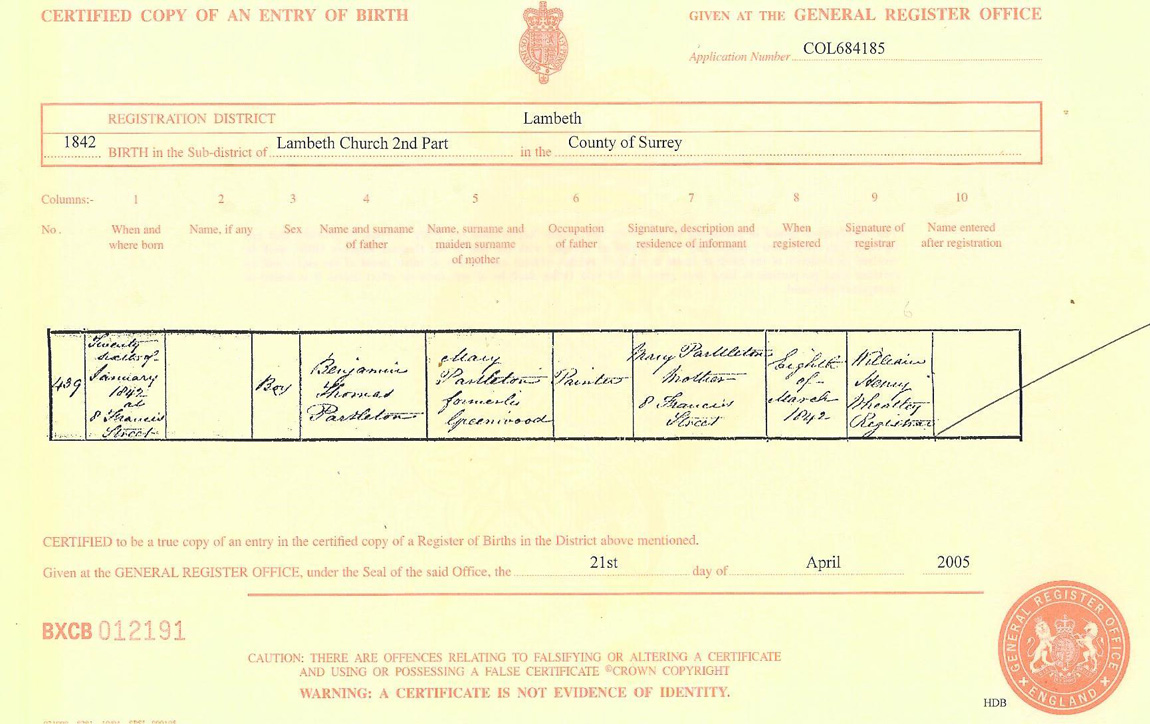

Mary was pregnant at the time of the census, and on 26 January 1842 she gave birth to her ninth baby. It is definitely to be her last:

Mmmm... that's weird. The mother and father are both clearly named on the document, but there's a gaping hole where the baby's name should be.

Compulsory state registration of births had been introduced in 1837, just five years before. The law required the birth to be registered within 42 days. But oddly, it was only the birth that had to be recorded. It was not necessary to specify a name. So, at the time of registration, Benjamin and Mary couldn't or wouldn't come up with a name for their baby. They later settled on Charles, in spite of the fact that they had already had a baby Charles who died in 1839. Perhaps they were arguing about this, which might explain their tardiness.

So there they were, Benjamin Partleton, house painter, his wife Mary, and their six children aged 0 to 16. What could possibly go wrong?

In 1843, Benjamin gets a painting job at a posh house at Clapham Common, Battersea, for a customer called Henry Thornton. It's not very close to Benjamin's home, but no doubt the job's worth a few bob, so he travels there, perhaps down the Clapham Road in a horse-drawn omnibus:

We may imagine Mary at home looking after little baby Charles and her other young kids. There's some bad news on its way. How the news got to Mary, we don't know, but perhaps she became worried when Benjamin didn't come home that night.

Benjamin at age 43 had died while out on his painting job.

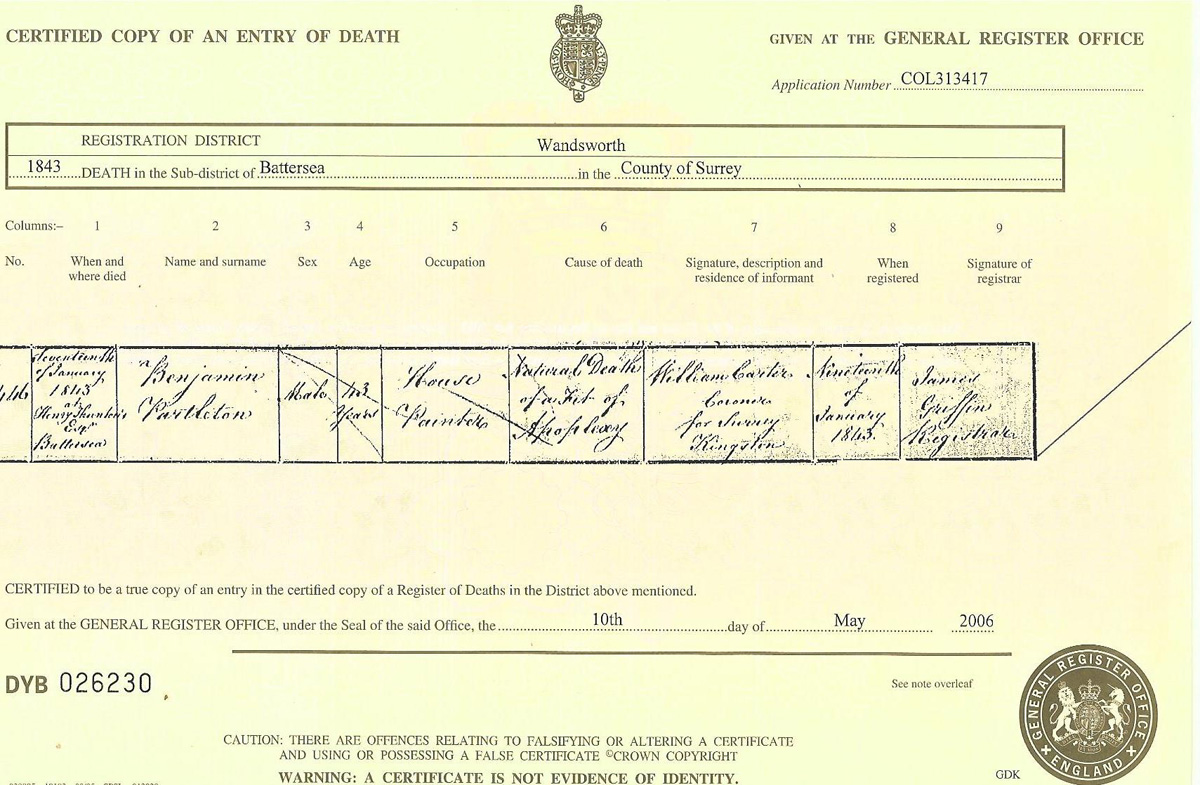

His death certificate gives the cause as a 'fit of apoplexy' [19th century terminology for a stroke], 'at Henry Thornton's Esq, Battersea'.

This very specific place of death was something of an enigma to us for some time until September 2008, when the Partleton Tree was contacted by Lynne Robinson who came across this page while surfing the net and immediately recognised the name Henry Thornton Esq.

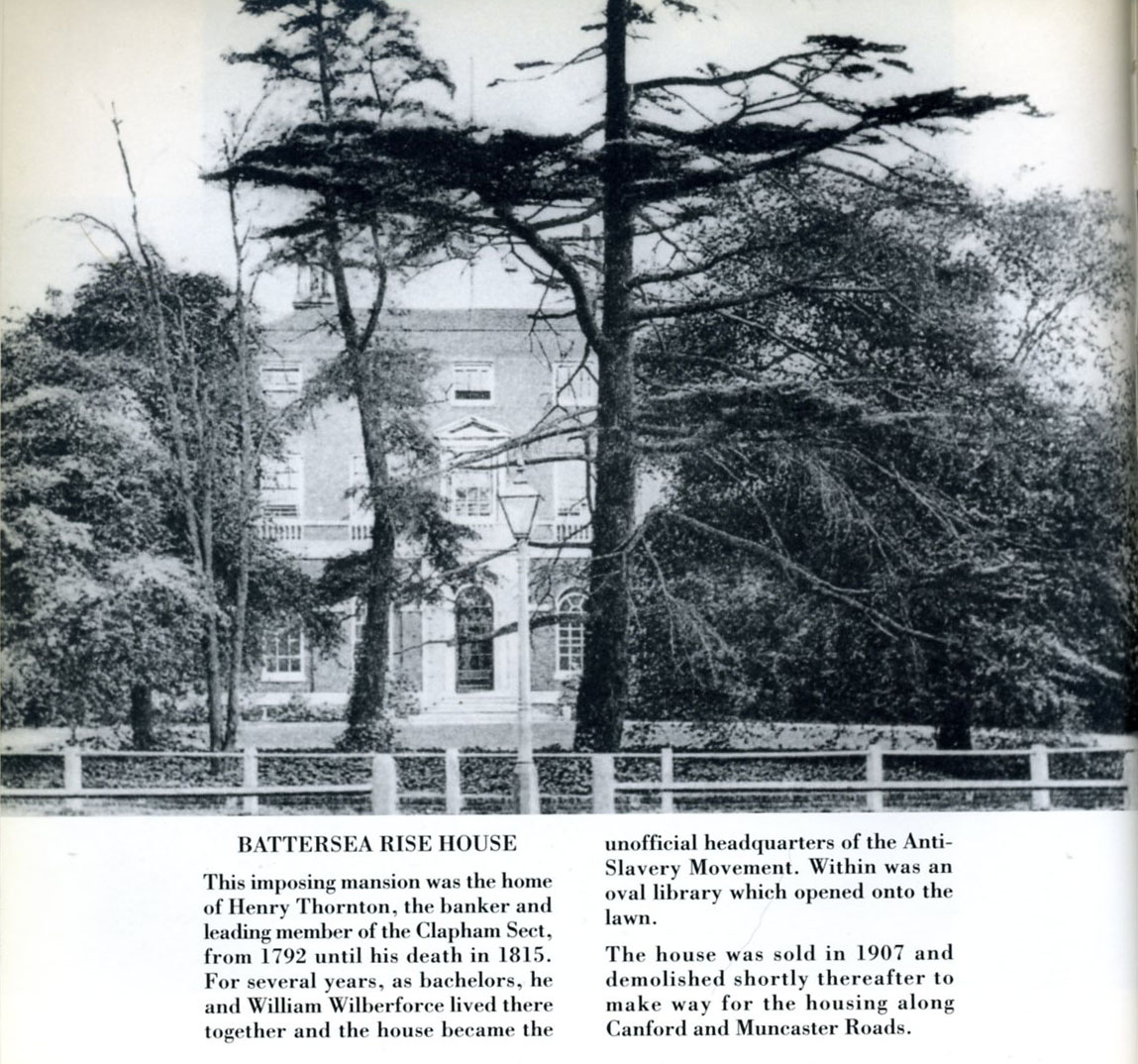

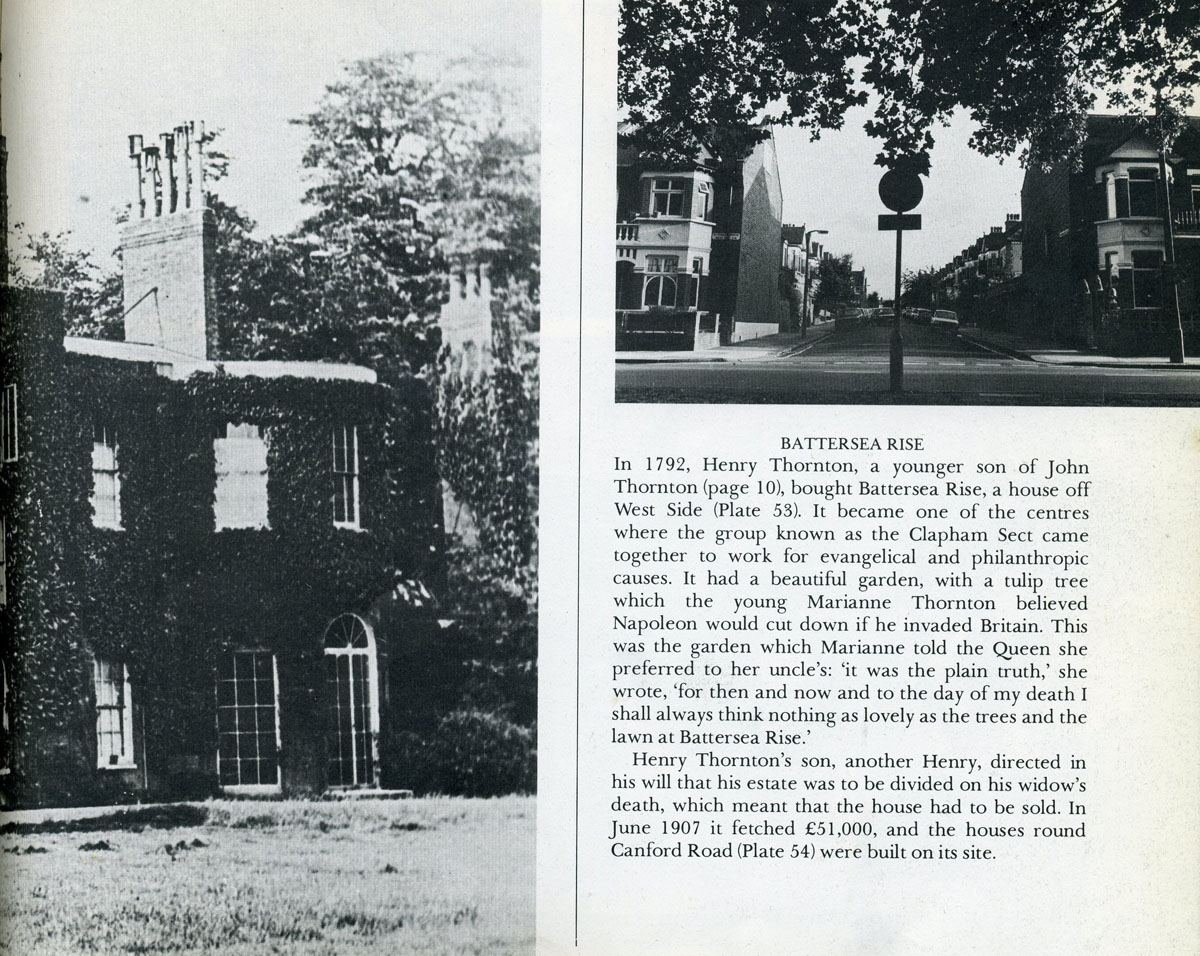

As a consequence, uniquely, we have some photographs of the house where Benjamin died - thanks Lynne! Henry Thornton (1800-1881) was a well-known banker and philanthropist in Battersea whose father, Henry Thornton (Sr), was a famous anti-slavery campaigner.

Here's the house where Benjamin died:

The picture above is the front of the house; the picture below shows the rear view. Nice place. Very nice:

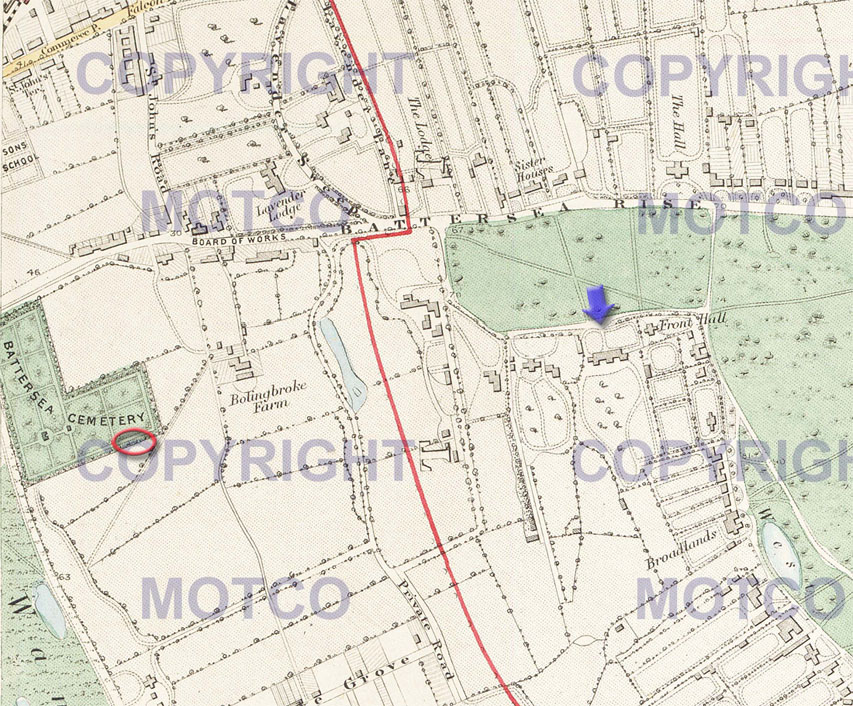

Here's the location of Battersea Rise House in a map of 1860, on the western edge of Clapham Common, at the point of the blue arrow:

Below is the same map in 2008. All the fields have been developed into streets. You can map the streets along the old field boundaries. If you are wondering what the red circle is on the maps - it's Mallinson Road, where the author of this web page was born, in a house backing on to Battersea Cemetery. I never knew it was just 300 yards from where my great-great-great-granddad died:

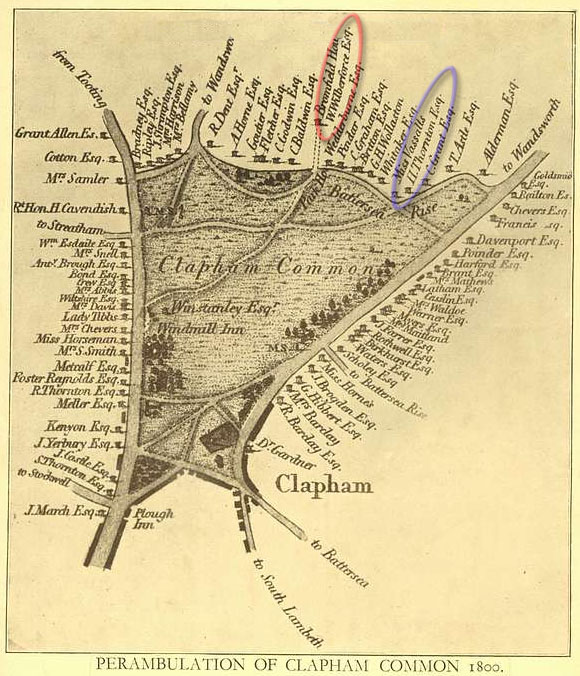

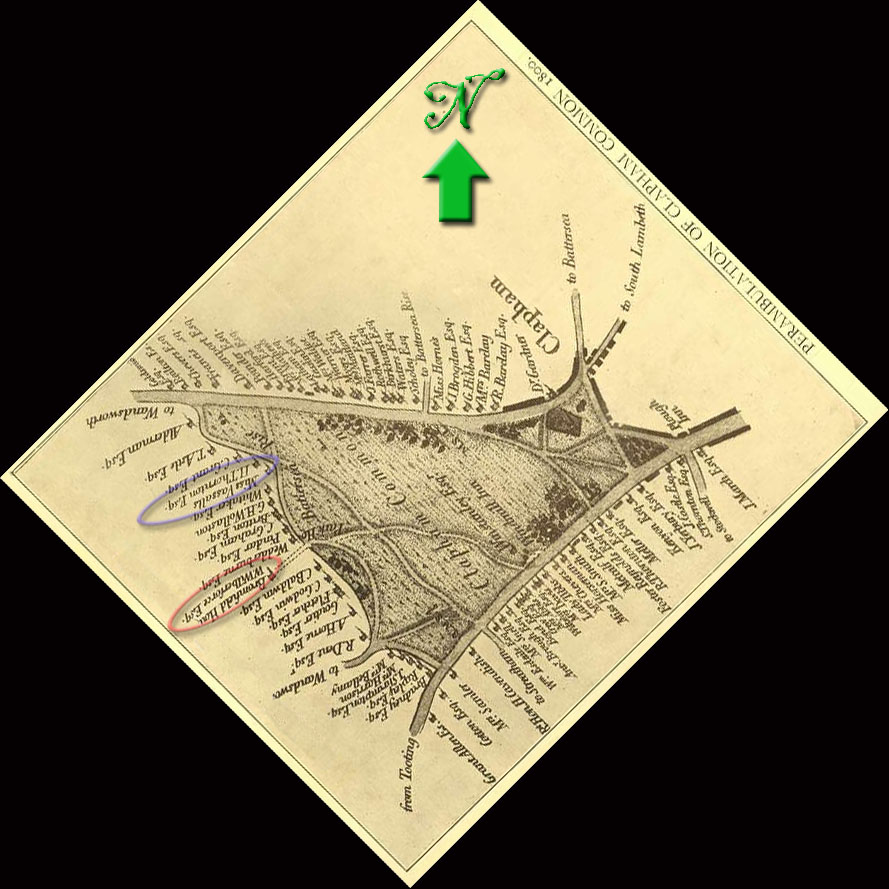

Here's a charming drawing of 1800 proudly identifying the homes of the posh residents around Clapham Common which include Henry Thornton Esq Sr, who founded the group of reformers called the 'Clapham Sect', and his good friend, the very famous anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce. Also on the map is Henry Cavendish, the scientist who discovered hydrogen gas:

If you think Henry Thornton's house has lifted up its skirts and moved, that's because aligning the map with north was not of much interest to the artist:

Below we see Henry Thornton Esq Jr, banker, philanthropist, Fellow of the Royal Society, at home at Battersea Rise House, Clapham Common in 1851. Although a widower, he has in his household a butler, a footman, a groom, a cook, and six other servants. [By 1871 this number had grown to 20 servants]

The name Henry Thornton lives on in Battersea in the form of Henry Thornton School.

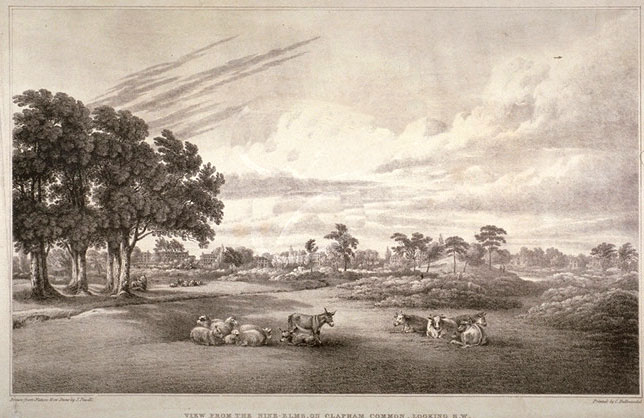

Before we get back to Benjamin, this is just too good an opportunity to pass by to see what old Clapham Common used to look like.

In 1843, cattle still graze on the common:

In later Victorian times, this chappie is selling ginger beer on Clapham Common to thirsty visitors in the summer:

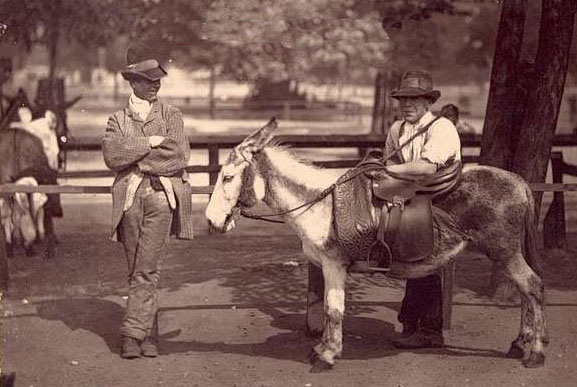

And these decidedly dodgy-looking fellows are offering donkey rides to children:

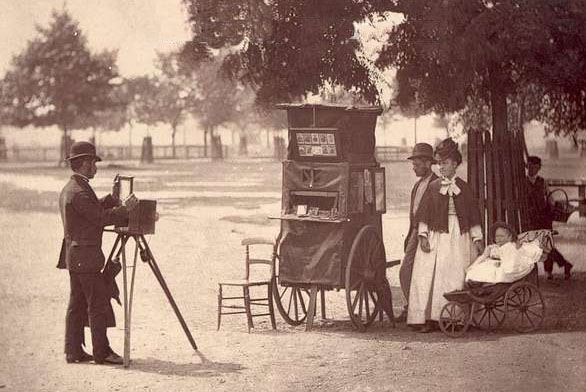

And here's a Clapham Common photographer picking up business from passers-by, with his mobile darkroom:

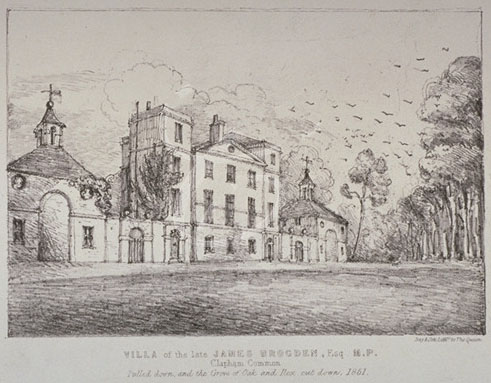

Below we see the home of Mr James Brogden Esq, Member of Parliament, on the north side of the common. I just love the look of this house, rooks swirling in the trees. This building was pulled down in 1851 and the grove of trees chopped down:

Here's Cavendish House, home of Henry Cavendish, on the south side of the common:

This one is the home of his near neighbour Lord Teignmouth:

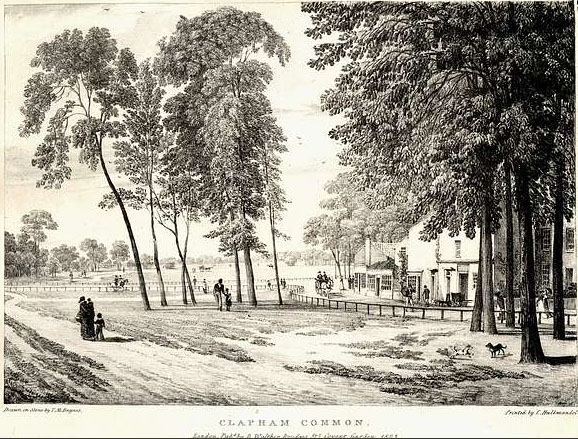

Here's a view of the common from 1823:

All in all, Clapham Common was a pretty nice retreat for London's rich, and though it's still very much an open space, it's quite a rural contrast with how it looks today.

Let's get back to Benjamin. He died of a stroke aged just 43. And his brother Thomas Partleton had also died of a stroke in 1838, aged just 34. Linking these two deaths is Benjamin's brother Stephen Partleton who had died in 1836, also aged just 34. Stephen died of lead poisoning, and all three brothers had been house-painters. My point is that Benjamin's premature death was probably also caused by lead poisoning as a contributory factor.

Five days after his death, Benjamin was buried - not at Battersea Cemetery near to his place of death, but near his home, at the old Lambeth Burial Ground on Lambeth High Street:

For Benjamin's wife Mary, the whole world has collapsed. Not only does she have to grieve her husband, but she is now penniless, has no income, and has to deal with what is to happen to her six children.

Fortunately, she is able to turn to her family, the Greenwoods. Her older kids Benjamin (18), William (16), Eliza (14) are probably old enough to get work and fend for themselves. But she also has Marion (10), Joseph (7) and my great-great-granddad Charles Greenwood Partleton (1) to take care of.

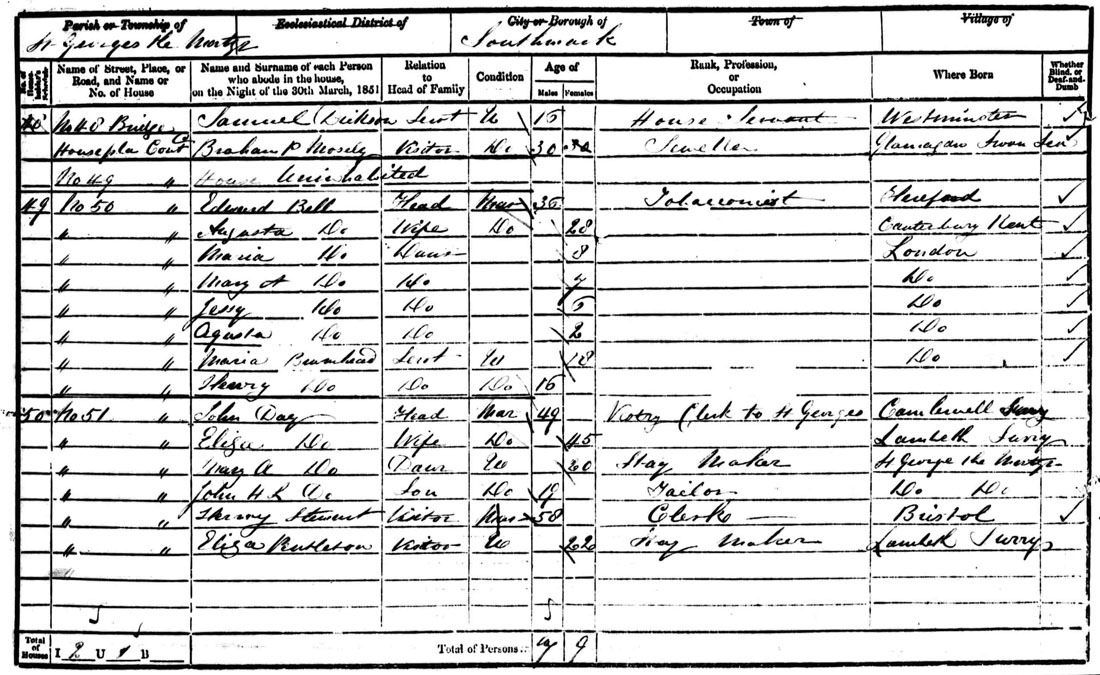

Eight years later we can search for the dislocated family in the 1851 census:

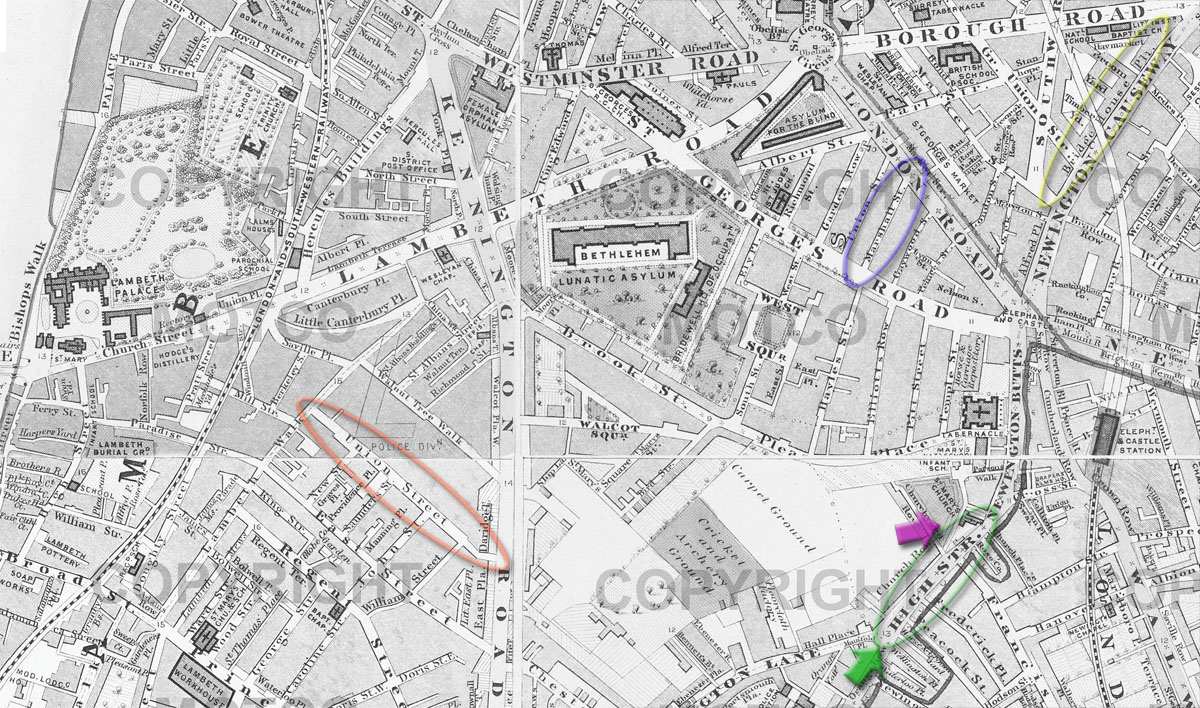

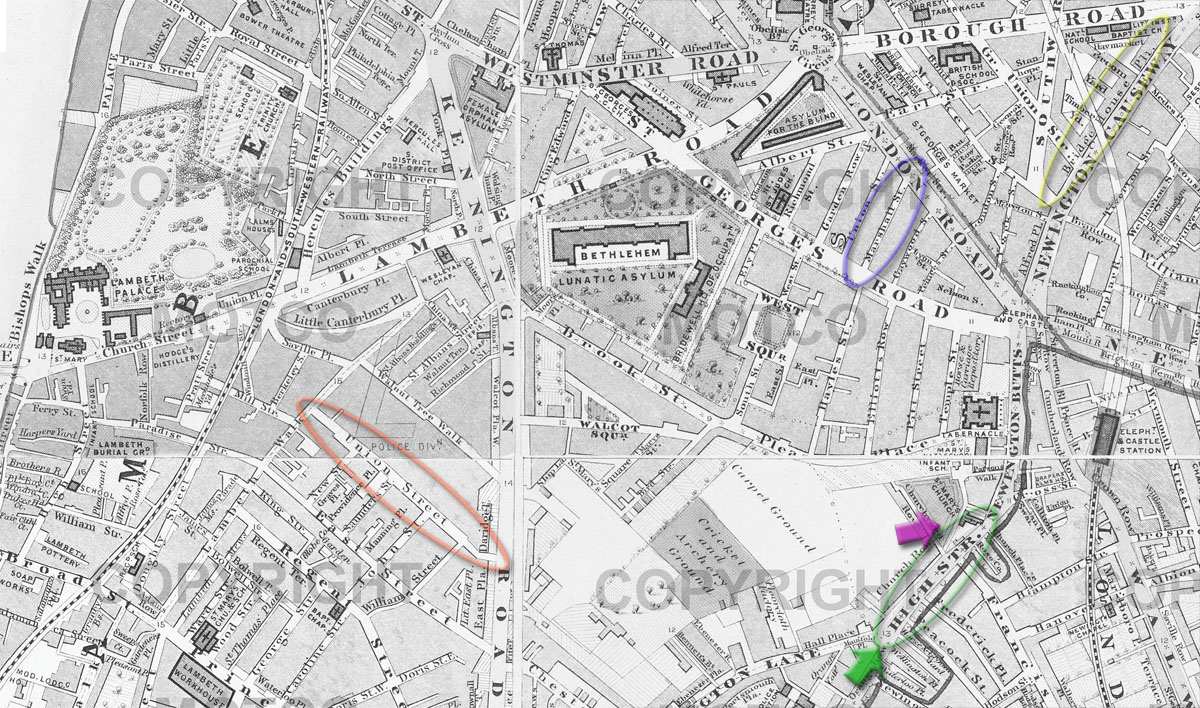

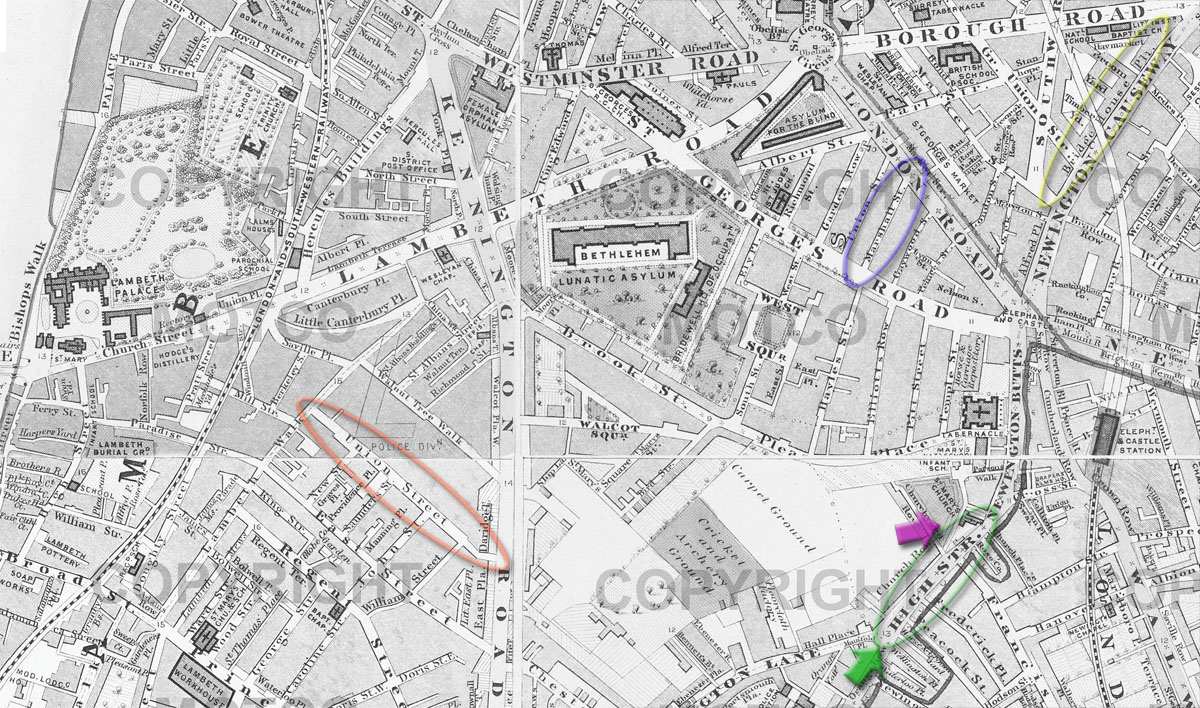

Above we see Mary, now 51, who is taking in laundry to earn a crust, lodging in a single room with her son Joseph, now 14, who also has a job. Mary's living at Marshall Street, near the Elephant & Castle, which is circled in blue in the map below:

Some of you will no doubt know that the Bethlehem Lunatic Asylum in the centre of the map was more commonly known as Bedlam. This is the origin of the English word meaning mayhem.

Next we see Mary's daughter Eliza, just 14 when her dad died, was now 22 and living just round the corner, a visitor at the premises of Mr John Day at Bridge House Place, circled in yellow. It looks like Eliza is a friend of John Day's daughter Mary Ann:

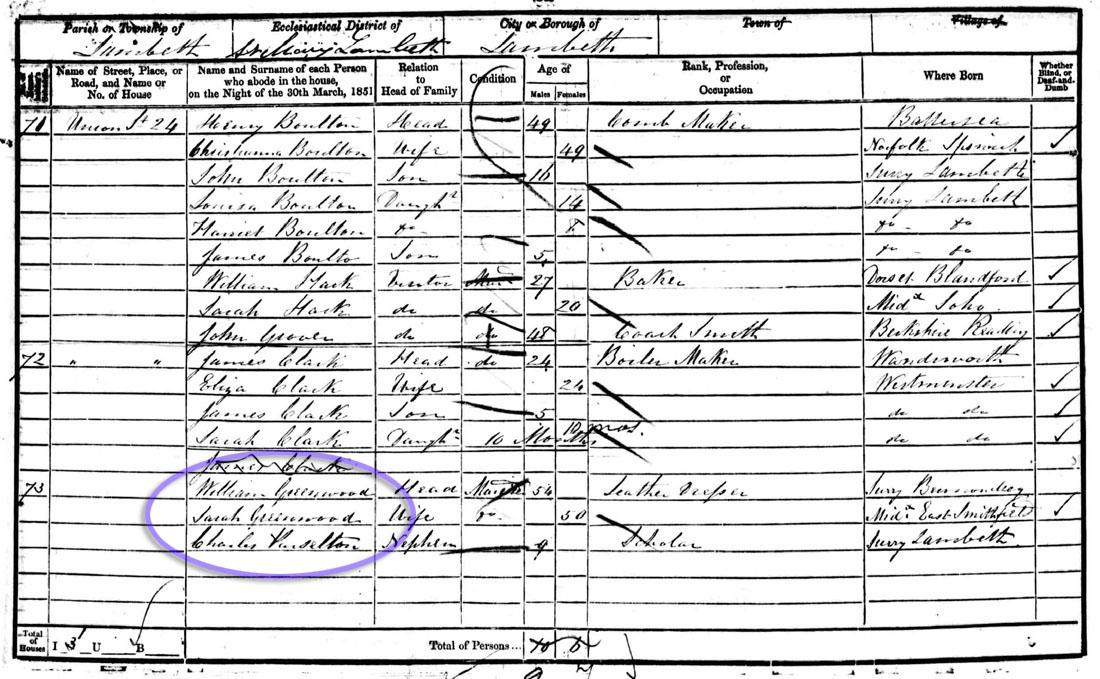

Next we see Charles Greenwood Partleton who was just 1 when his dad died. He's a 9-year-old scholar being looked after by his uncle and aunt William and Sarah Greenwood:

The Greenwoods live on Union Street, circled in red in the map:

The other three of Mary's children... Benjamin, her oldest, can't be found in 1851 but turns up later. Mary's daughter Marion, who was only 10 when her dad died, is now 18 and is in domestic service in Whitechapel, east London. And finally William George, who is now 24, is living in Holborn.

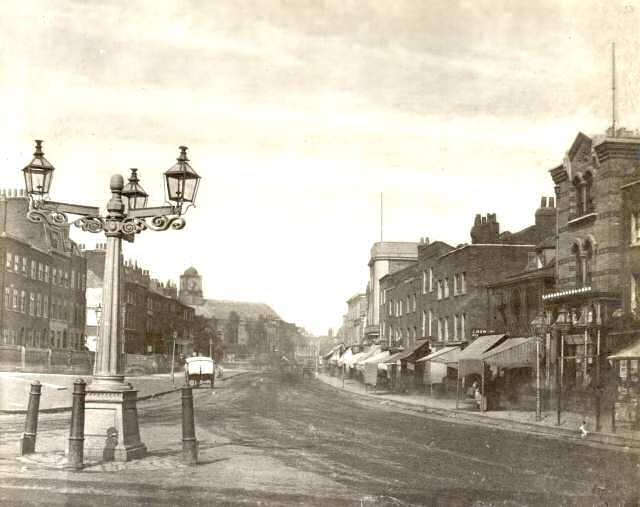

I can't help feeling the ten years after her husband's death were all a bit too much for Mary Partleton nee Greenwood. In 1855 she was living on Newington High Street, circled in green in the map above.

We can step right into Mary's shoes for a moment because we have a photograph of 1860 of Newington High Street seen from the viewpoint of the green arrow in the map. She's living in one of these houses:

Mary died two days after Christmas Day in 1855:

The cause of Mary's death is 'paralysis'... rather vague. Present at the death was her sister-in-law, Sarah Greenwood.

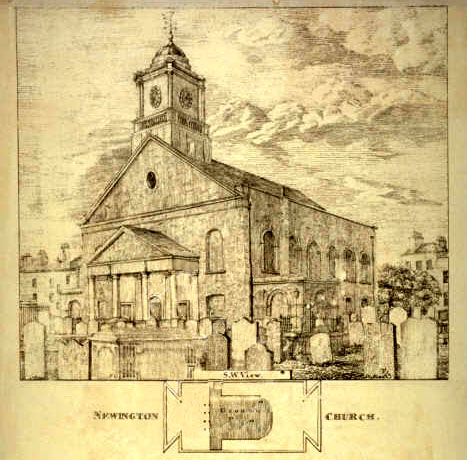

Mary died on High Street Newington aka Newington Butts, close to the church of St Mary Newington which we see in the engraving below:

This engraving is drawn from the viewpoint of the purple arrow in the map below:

We can see from the map that Mary died less than 100 yards from the church. However - surprisingly - we find that Mary's grave was not to join those in the churchyard of St Mary Newington, or anywhere in Lambeth.

What we see below - thanks to Partleton Tree correspondent Coralie Purnell - is the burial register for unconsecrated ground: Victoria Park Cemetery, Hackney, in the East End of London:

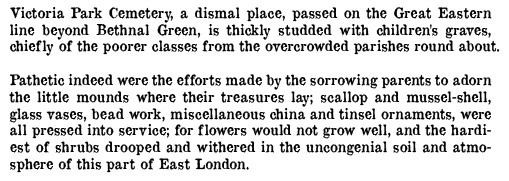

The cemetery at the local church, St Mary Newington, was ram jam full, literally overflowing, and stopped taking burials on 04 December 1854. The parish had to secure a sufficiently cheap new resting place for its poor to be buried - and found it at the commercial cemetery near Victoria Park in Hackney; the parish weren't worried that this graveyard was unconsecrated. Burials at Victoria Park Cemetery in the 1850s cost just 7 shillings. Compare that with Nunhead Cemetery which was much nearer in South London, but cost £1 (ie 20 shillings). That's why we find Mary's body being carted halfway across London.

Looking closely at the above register, we find Mary's age incorrectly noted at being 37. It should be 57 - but be assured, it is definitely our Mary.

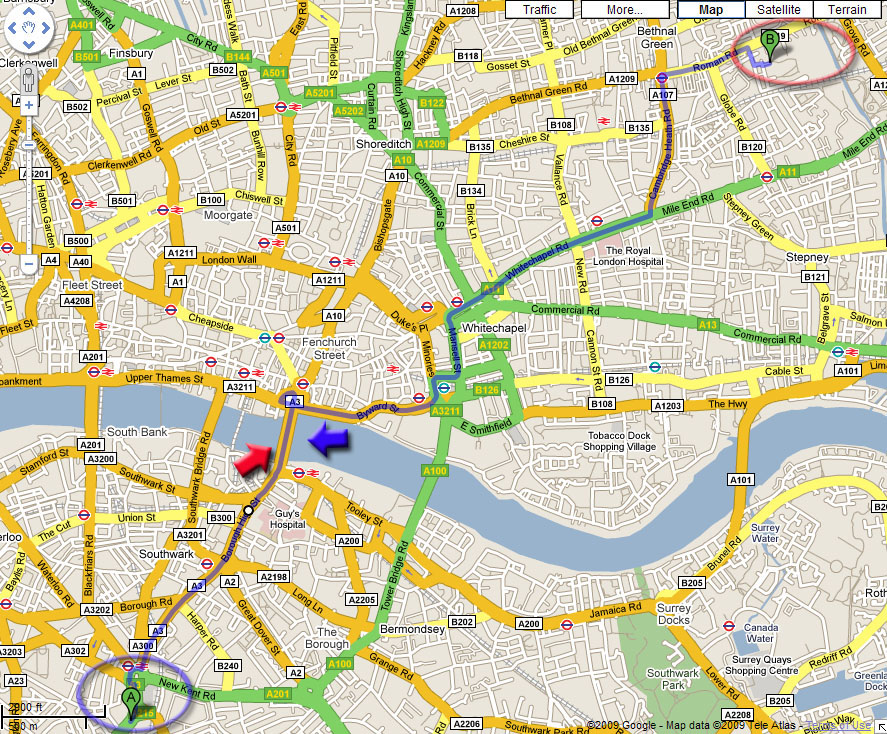

So, lets locate this graveyard in Hackney:

Mary's body was transported about 5 miles across London from Newington, circled blue, to the cemetery, circled red, almost certainly crossing London Bridge [there was no Southwark Bridge or Tower Bridge in 1855], on a horse-drawn carriage. Below we see London bridge from the viewpoint of the blue arrow (1841):

Here it is again in the late 1800s from the viewpoint of the red arrow:

Finally, here it is in 1980:

I can't show an arrow on the map for this picture of London Bridge because I took it myself on holiday in Arizona in 1980. The bridge was sold to American entrepreneur Robert P McCullough in 1967; every stone was numbered and the important bits were transported to the Arizona desert. The price... $2,460,000. A good piece of business.

Back to the burial of Mary Partleton nee Greenwood...

Here's an 1862 close-up view of the the location of Victoria Park Cemetery, close to the old Regent's Canal.

And here's a modern satellite view of the same spot:

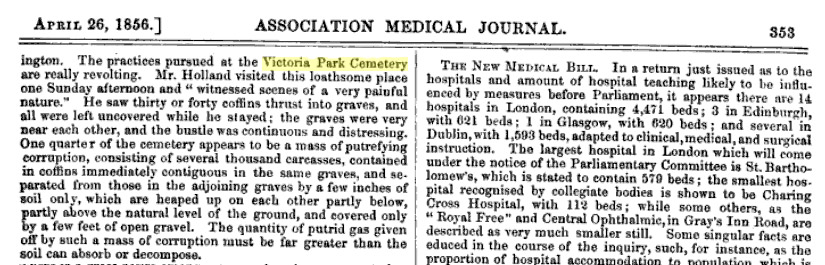

Victoria Park Cemetery was a private enterprise started by a limited company in 1845 to take advantage of the market for burials created by the inability of church graveyards to accept any more dead. Unfortunately, Victoria Park Cemetery's customers were all dead, and not only dead, but dead poor. The cemetery went bankrupt in 1853. The business was bought out by one of the directors who carried on regardless, which is why we find Mary being buried there in 1855.

Forgive me if I resort to a little primary-school maths at this point. Victoria Park Cemetery is 300m by 200m which is 60,000 square metres. If we allow 2m x 1m for each grave, that's an absolute maximum of 20,000 graves. Absolute maximum.

Let's have another look at that burial register:

We see from the above that in the month between 25 November and 25 December 1855 there were 51 burials in Victoria Park Cemetery. But look closer: the above page from the register is only for people whose name began with the letter P. Since Ps represent 5.5% of names, this equates to 927 per month, total. This is over 11,000 per year. And since Victoria Park Cemetery is 11 years old, by the time Mary Greenwood is buried there, this tiny plot has swallowed over 100,000 bodies; that would equate to a plot of 30 inches by 30 inches each - but these ain't cremations. The burial ground has been overfilled five times over.

But that's not the end of the agony. The cemetery continued in business at least a further 21 years, until 1876, and there were apparently burials until 1882. By this date this bloated plot had interred at least ten times the number of bodies it could possibly have absorbed, probably fifteen times, maybe twenty.

Actually, according to Tower Hamlets Council, there are possibly half a million people buried in this tiny plot. Twenty-five times what my simple calculation allows. How was this seemingly impossible task achieved? Simple:

What Mr Holland doesn't mention is that, after the ground-water levels were lowered in the area by new sewers, you can forget the old saying of 'six feet under'. At Victoria Park Cemetery, the bodies were buried, starting at an amazing 5 metres depth, and the coffins simply stacked on top of each other with a token amount of dirt between the layers. The bottom of the stack no doubt decayed and collapsed under the weight with the passage of time, facilitating further layers on top.

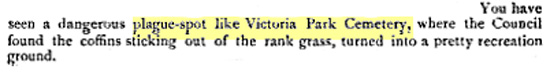

After its closure the neglected piece of land rapidly deteriorated and is quoted in A History of the County of Middlesex as being used by 'ruffians' for gambling.

The Disused Burial Grounds Act, 1884, prevented any building on the site, and in 1894 it was converted to a recreation ground. Usually in the cases of old redundant churchyards, the remains were dug up wholesale by the Victorians and removed to the new burial grounds outside London such as Brookwood, but I don't think this would have been possible at Victoria Park Cemetery, so I'm going to assume that nearly all of the half-million are still under there, including my g-g-g-grandmother Mary Ann Greenwood, who is probably down quite deep.

In spite of the depth of the graves, they had to come to the surface eventually. The following year, 1895, we find a reference to the previous terrible state of this site in the Selborne Magazine:

Victoria Park Cemetery was never consecrated. It was really a sad place for Mary Greenwood to find her last resting place, as we see in the contemporary book Imperial London, by Arthur Henry Beavan:

There is a surviving photo of the cemetery. Though we can see clearly shallow and collapsed plots, it doesn't appear so bad in this view as the descriptions we have read:

The recreation ground remains today, with one remaining token gravestone to mark its former use, on exactly the same footprint as the old cemetery. It is known as Meath Gardens.

But one part of the cemetery remains - the Gothic arch gateway, built in 1845, through which Mary passed on the way to her burial. It's located in the yellow circle in the aerial photo above. Note the initials V.P.C. [Victoria Park Cemetery] in the suitably bleak photograph below:

And lastly we see the entrance gate to Mary's final resting place looking much more cheerful though somewhat incongruous among the 20th century apartment blocks:

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... or would you like to discuss any of the history... or if you have any observations or comments... all information is always welcome so why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'In Their Shoes' Page.