Benjamin Partleton (1774-c1833)

Part I

Since Benjamin is one of our oldest known ancestors, I thought I'd go to town - literally - on his page.

Benjamin Partleton - son of Thomas Partleton and Hannah Dunsdon - was born in the parish of St James in London. This church is known both as St James Piccadilly and St James Westminster - which is confusing - and I've had to use both names in this page depending on which record we are looking at.

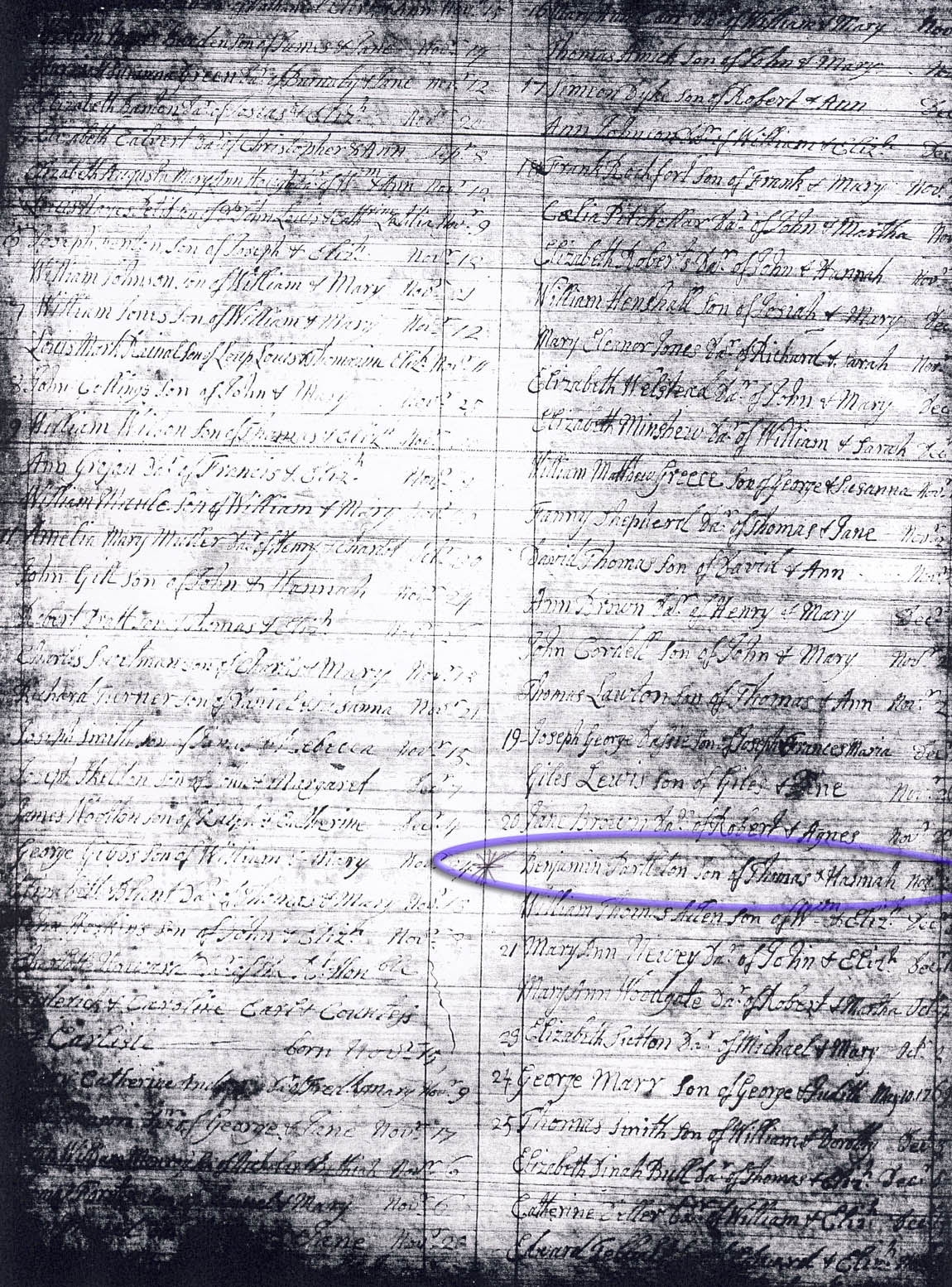

So, to the Parish Register for St James Westminster of November 1774, and we find Benjamin's baptism circled below:

Benjamin was the youngest of eight children, the fate of which only one other, his big sister Hannah, is known. Below we see Benjamin, highlighted red, and his family.

The probability is that the middle six of Benjamin's brothers and sisters died young, though we have no direct evidence of this, apart from Elizabeth of 1761 - because another child is named Elizabeth in 1769. It's also possible that the girls might have married and lived long lives under other names, but we haven't found any marriages. As for the boys, whatever became of them, if they lived, they left no progeny.

Consequently we know for certain that ALL subsequent Partletons who appear in the London censuses from 1841 to 1901 are descended from Benjamin, and moreover, ALL London Partletons today, are descended from this man.

Just to be sure we know where Benjamin is, here's a modern map:

So, let's make a journey the church of St James Westminster to see the christening of Benjamin in 1774. Below we see the church, which I will remind our gentle readers, is also known by the name of St James Piccadilly:

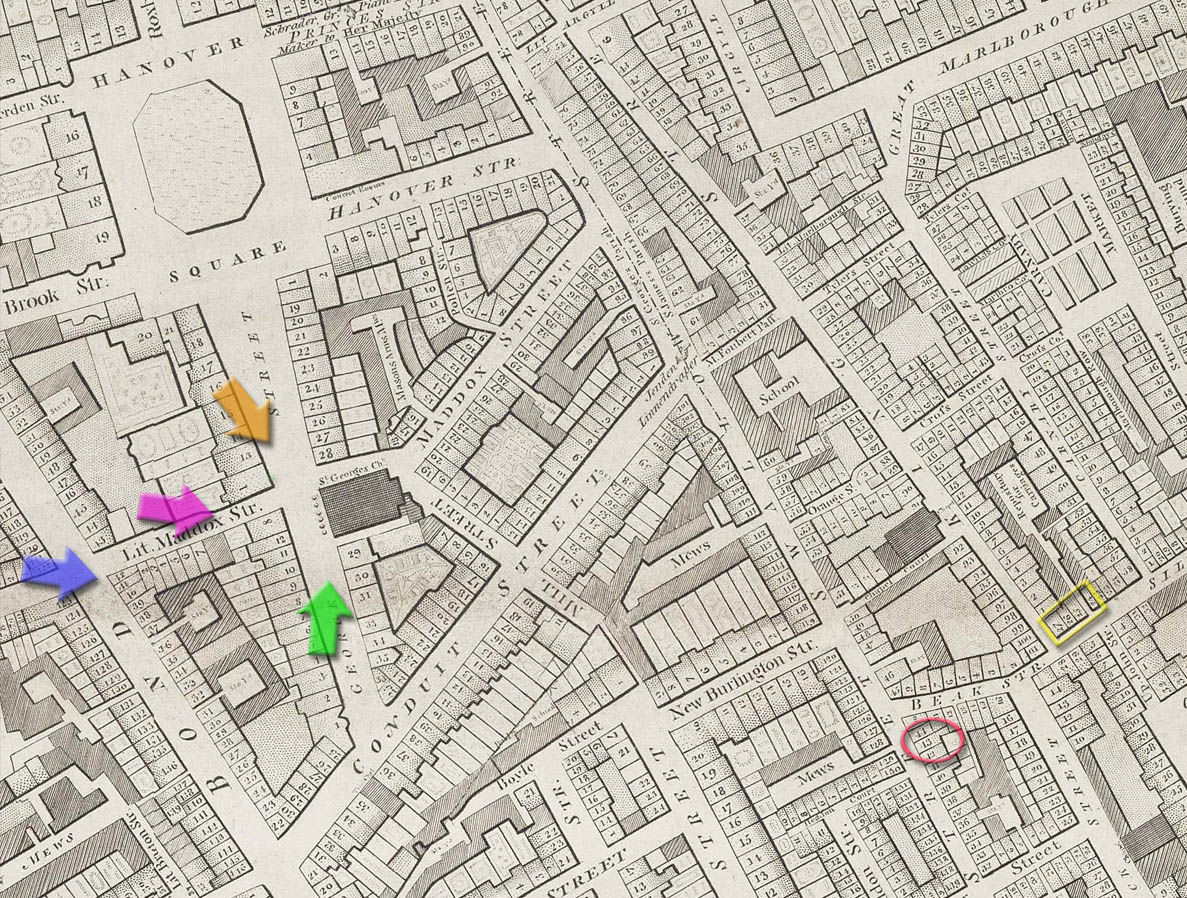

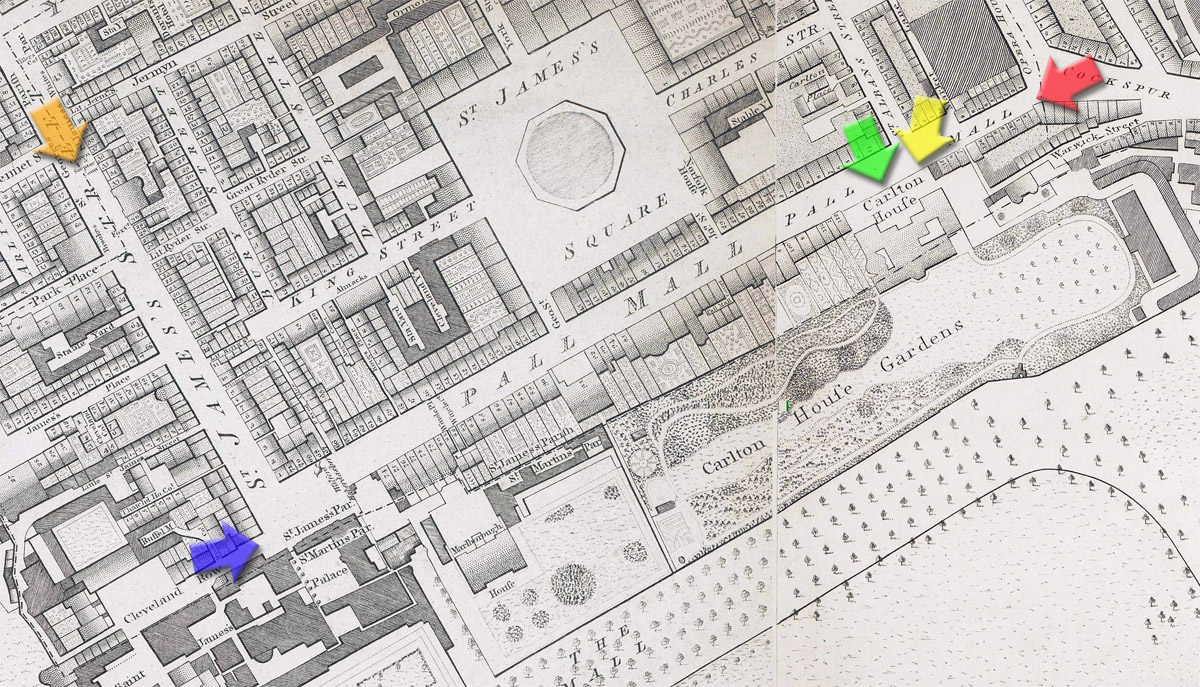

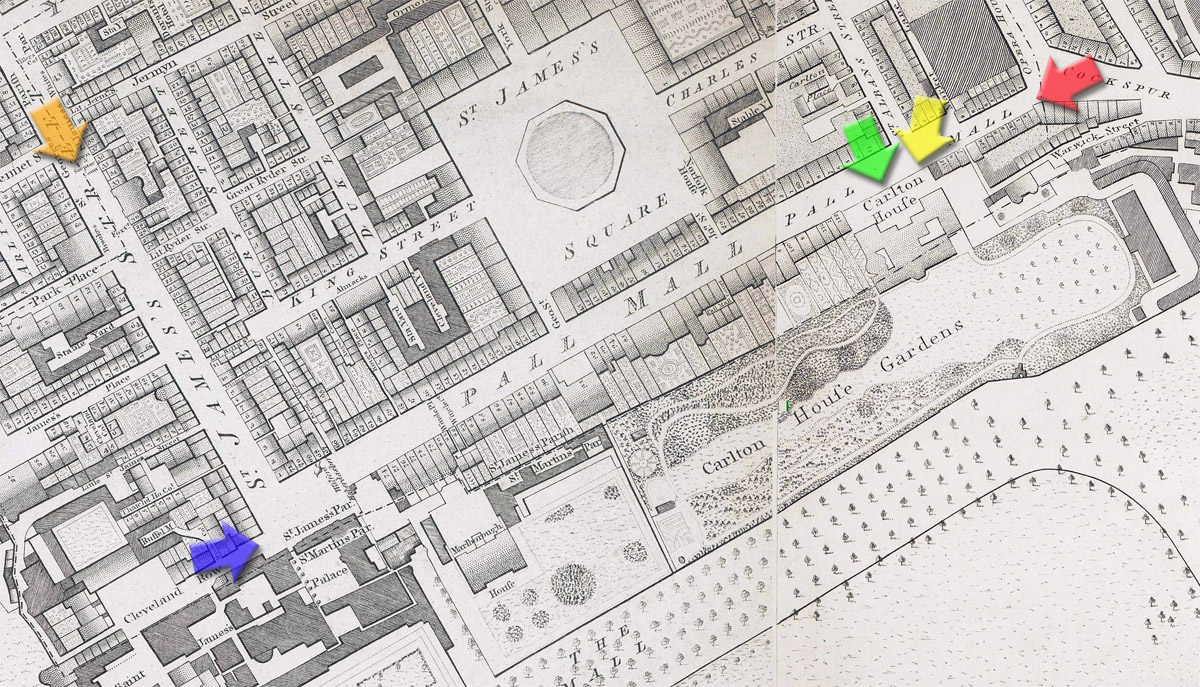

This view of the church is seen from the viewpoint of the yellow arrow in the map below, from Jermyn Street, spelled as German Street in the map.

The boundary of the parish of St James is shown outlined in blue. This map was published in historian John Strype's amazing Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster in 1720:

We know that Benjamin was born and raised in the Parish of St James, but from the time he is ten years old, in 1784, we know exactly where he is living: 43 Swallow Street, near the corner with Beak Street, circled in the red in the map above.

How do we know this? Because of the document below:

What we see above are the Watch Rates for the Parish of St James, Church Ward, for the year 1784. On this record we see Benjamin's dad, Thomas Partleton, whose rent is £16 a year, has paid rates of 6 shillings and eight pence. This is a rate of exactly 5d per £, roughly a 2% tax rate on your rent.

Thomas and his family weren't in the book at this address for any previous year, though his neighbours are, so we can identify the exact year that the Partleton family moved to Swallow Street: 1784.

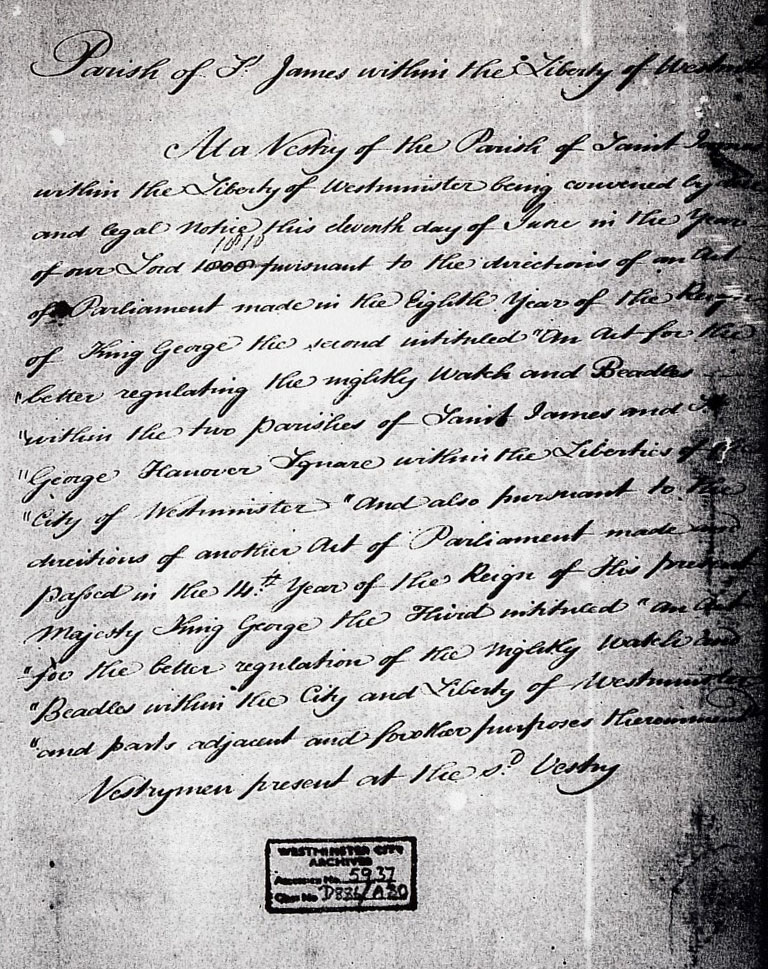

"But what are Watch Rates?" I hear you ask. The description can be found on the front page of a typical Watch Rate book for St James:

We learn from this that Watch Rates are paid 'for the better regulating the nightly Watch and Beadles'. Benjamin's dad is coughing up 6/8d a year to pay the wages of the parish night-watchmen. In the 1700s there was no police force, and each parish had to organise its own law and order.

What we see in the fabulous photograph below is a night watchman, or 'Charley' as they were commonly known. Although this photo was taken in Lambeth in 1865, the gentleman concerned was photographed as a record of the last of a dying breed, replaced by the Metropolitan Police. I'm sure Benjamin would be able to tell you straight away what this man's job was:

This poor fellow had to stand up all night. He's got a staff in his right hand, a sword on his waist, and a rattle for raising the alarm tucked under his sash. Behind him is his night watchman's box, in this case a luxury brick version, but this was more often just a wooden sentry box in which the watchman had to survive the winter nights.

Night-watchmen were often accused of falling asleep on the job, and who can blame them?

When I located the cartoon of 1784 below I thought for a moment that I'd found an actual picture of the Westminster watchman, wouldn't that be great...

But sadly it's just a political satire. However, it does give a glimpse into the politics of the time. Depicted as the reliable watchman is Whig statesman Charles James Fox, sending his unreliable political opponents Lord Hood and Sir Cecil Wray and their mangy curs packing. He was an outspoken opponent of King George III whom he regarded as an aspiring tyrant. He supported the American Revolution, and was always on the watch for unconstitutional moves toward dictatorial powers for the monarchy... hence the 'watchman' analogy.

Below we see another cartoon [1816], by the genius illustrator and satirist George Cruickshank. Tom and Jerry, two dissolute wealthy dandies about town, making a real nuisance of themselves at Temple Bar. Tom, intoxicated as usual, pushes over the Charley's box. Jerry, accompanied by two ladies of the night, thinks the whole caper hilarious. The Charlies, one of whom is raising the alarm, are not depicted very sympathetically either:

Back to Benjamin. In 1784, the streets of London were lit only by oil lamps, as we see above in Cruikshank's picture. If young Benjamin and his dad ever had to go anywhere on a dark night, it must have been fairly tricky to navigate with just a few glimmers from the rudimentary street lighting and from light spilling from the houses.

A similar, cautionary and hilarious view of the state of law-and-order in the streets of London is provided by Thomas Rowlandson - another comic genius - in his 1806 engraving below, 'A Cake in Danger'. The Cake is contemporary slang for a fool, or gullible, innocent person... the subtitle reads; 'Careful Observers, studious of the Town, | Shun the Misfortunes that disgrace the Clown.'

Swallow Street, where Benjamin grew up, was notoriously rough and ready; contemporary newspaper reports abound with stories of thefts, pickpockets and prostitutes, so the scene we witness below, a sleeping watchman with his pipe tucked in his hat, and the mark being relieved of his handkerchief by two ladies of the night, would be quite familiar to him:

We should be clear here that Benjamin's family are of comfortable but modest means, in the building trade.

In contrast with its posh surrounding streets, the road where Benjamin lived, Swallow Street, was a higgledy-piggledy landscape of houses and stables and alleys of different sizes and types. Benjamin could observe its width varying widely from narrow to broad when he made his way northwards along its muddy surface.

John Strype had visited it in 1720 for his publication A Survey of the Cities of london and Westminster, but wasn't particularly impressed:

However, their neighbourhood - the parish of St James - was the among the grandest and poshest in London, and still is.

UK ambassadors in foreign countries are titled 'Ambassador to the Court of St James' because St James's Palace, which we will see shortly - although the Queen never lives there - it is technically the official address of the British monarch and her court.

The church where our Benjamin was christened, St James Westminster, was designed by the famous architect Sir Christopher Wren. Building work started in the year 1676, ten years after the Great Fire of London, and it was completed in the year 1684. It was a new church, not one of those which were replaced having been destroyed in the fire.

So the church was already 90 years old when little Benjamin was baptised there. Below we see the interior exactly as he saw it in 1774, blinking through his little peepers; very, very grand:

In 1686 a font had been installed in the church. It can be seen in the foreground of the Victorian print above, and it is still there today, well over 300 years after its debut, and we will see more of it in a moment, but first let's see this 20th century photograph of the interior of the church of St James Westminster:

Ok, now let's get back to that font, because it is really, really worth a look. It was sculpted out of solid marble by the genius woodcarver Grinling Gibbons, and it depicts the Garden of Eden:

The website of the church of St James Westminster describes this object as a treasure, and it's fair to say that I wouldn't disagree with that.

We don't often get a chance to make a solid connection with the past on these web pages. Usually it is documents, dates, websites, registers, information, people and places long gone, ethereal, insubstantial. But here we can just picture proud parents Thomas Partleton and Hannah Dunsdon standing right in front of this solid object, baby Benjamin having his head wetted on that cold November Wednesday in 1774.

Incidentally, this is the same church in which Thomas and Hannah had been married fifteen years earlier in 1759, and they'll be very familiar with that font because all seven of their children have been baptised at it.

Before we go any further with the story of Benjamin, having seen that font, I needed to know a bit more about Grinling Gibbons:

Above we see one of his wood carvings for another Wren building, completed in the same year as St James Westminster...

"Hold on, hold on," I hear you say, "we are getting way off track here; this is a family history website," and you are right. We'll let go gracefully, just mentioning that Grinling Gibbons was born in Holland in 1648 and moved to London in 1667, working on St Paul's Cathedral and many other famous buildings with Wren before passing away in 1721.

So, let's return to the Church of St James Westminster. In November 1940 it was damaged by bombing in the blitz. The roof was burned by incendiary bombs and a huge bomb crater splatted in the road in Piccadilly right at the end of Swallow Street:

Left:

The Times, 20

November 1940

Left:

The Times, 20

November 1940

Some temporary, wartime repairs were made to a part of the roof, allowing a small part of the church to continue in use:

But for the most part, St James church remained bombed-out, and it took a while to get round to putting this mess straight, as we see from the newspaper report below, from the Illustrated London News of 09 August 1947:

Most of the repairs were completed in 1954, but the tower and the spire - which had already had to be rebuilt in 1711 when the original developed an alarming tilt - remained burned out, as reported in 1955:

In the photograph below we see the church in 1960, with the roof now fully repaired but still looking rather forlorn without a spire.

The church had to wait till 1968 before the spire was finally restored as we see in the modern photograph below. Money must have been tight, and the good intentions of the 1950s set aside, because - amazingly - this spire is a replica made of steel and fibreglass! Not surprisingly the fibreglass has since cracked, is leaking, and requires replacement.

In May 2007, the church held a 'raise the roof' concert which raised almost £30,000 with a musical evening and readings by actors Diana Rigg, Anthony Andrews, Edward Fox and John Standing. This is marvellous, except the required amount is £3,500,000.

Left: The Rector Inspects some Solar Panels

Left: The Rector Inspects some Solar Panels

Anyhoo, back to Benjamin. His big sister Hannah, who had been born in 1760, was married to Thomas Foot on 19 November 1786. Benjamin was 12 years old, and it seems highly likely that he would have been present at his sister's wedding.

It's held, of course, at the church of St James Westminster:

So, after his sister's wedding, let's go for a walk with 12-year-old Benjamin around his neighbourhood.

Perhaps we'll buy him some cherries; they've been brought to London all the way from Kent, but watch out for the street-vendors scales, they're notoriously crooked:

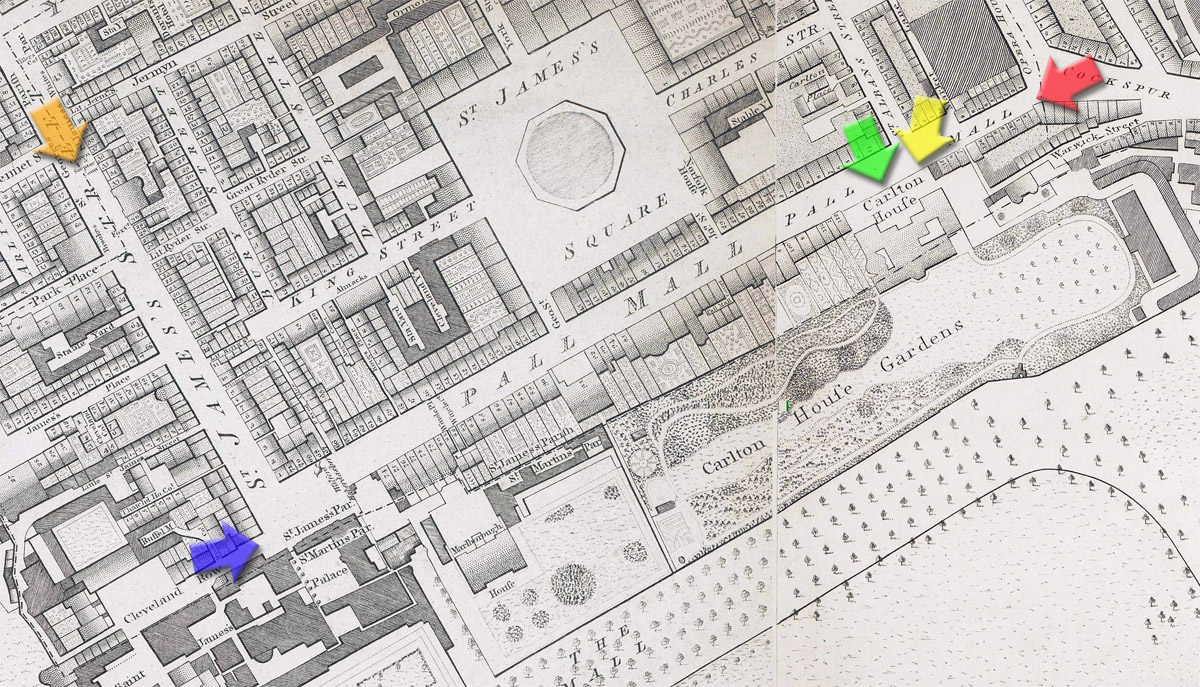

The above charming picture is labelled 'St James's Place', which we can see at the point of the red arrow in the map below, but in the modern photo we can see that she's actually standing next to the grand gates of St James's Palace (built in the reign of Henry VIII), from the viewpoint of the yellow arrow below:

St James's Palace was the actual royal residence of the King (George III at this time) during our Benjamin's lifetime. It was the predecessor to Buckingham Palace.

But let's step into Benjamin's shoes again. When he's eaten his cherries, perhaps he'll run an errand for his mum to buy some sausages for her to cook for the wedding guests. This will take him to St James's Market, at the point of the purple arrow - a posh indoor mart where there's a particularly good butcher's stall owned by Richard Wall. The year being 1786 is particularly significant for Richard Wall as it is the very year in which he founds his business.

If the name name Wall sounds familiar as a butcher, and you're from Britain, here's why; starting from his stall in St James's Market in the year Hannah Partleton was married, Richard Wall went on to create Britain's biggest butcher's business. His year of establishment is still printed on the packaging as we buy it in the supermarket today:

The street of Piccadilly itself was a a busy place where one would go to catch coaches departing for all parts of the country, and for inns and hotels servicing the travellers. Here's the West Country Mail about to depart the Gloucester Coffee House, Piccadilly, as drawn by artist James Pollard:

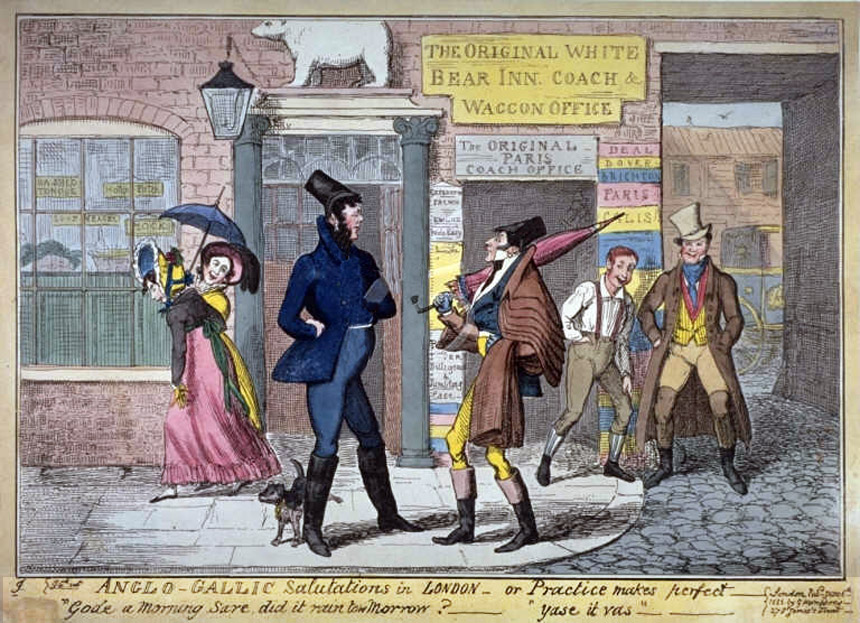

A little way up the road east of St James' church on Piccadilly was the yard of the White Bear Inn:

These traditional Coaching Inns often look just like the White Bear. To my eye they cast a resemblance to modern motels is the USA.

The painting we see above was executed from the viewpoint of the green arrow, which is White Bear Yard:

We get a view of the front entrance of the White Bear, from the viewpoint of the orange arrow in the map, and we see the coach destinations clearly advertised on the outside of the inn:

It's a rather xenophobic engraving by George Cruickshank showing two Frenchmen being mocked for their fashions and accents by passing Londoners, perhaps excusable in part. At the time of drawing, the long-running hostility between the two countries had recently been aggravated as adversaries in the Napoleonic wars. Our Benjamin Partleton in his 30s would have been acutely aware of the progress of the wars, even though - since to our knowledge he wasn't a professional soldier - he probably didn't participate in these.

Artist Cruickshank chose this location because it's where coaches from Paris arrived and departed.

Wolfgang Mozart lived in London with his family from 23 April 1764 until 30 July 1765 while he was a child prodigy aged 12, performing at court, and rubbed shoulders with the jostling crowds along Piccadilly which included Benjamin's dad Thomas Partleton. Mozart spent his very first night in London at the White Bear Inn which we see above. Coaches left at five o'clock every morning for Dover, Margate, Ramsgate, Canterbury and Rochester. Mozart recorded in a letter that he had been seasick during the channel crossing.

Piccadilly, in keeping with the whole of St James parish, developed as a very posh street, accommodating many grand houses of London's rich, and later, expensive shops and fancy hotels, just as it does today. Much of the original was built in the late-1600s, evidenced below, in a beautiful map surveyed by Fairthorne and Newcourt in c1658, where we see Piccadilly shown as 'from Knights Bridge unto Pickadilly Hall'. It's a country Lane, with no houses along its length, and we see how the district of Knightsbridge got its name, from the charming Knights Bridge over the river Tyburn at its western edge.

'The Way from Paddington' is modern Oxford Street, and comparison with later maps shows that the field boundary highlighted in blue is Bond Street! The future Swallow Street is circled in red.

In the painting below of c1630, where the anonymous artist stood at the viewpoint of the green arrow in the map above, and looked down towards Westminster Abbey, we can see the whole area is just fields. Painted looking south, and standing where Piccadilly would later be, we can see numerous points of interest:

1. Part of the village of Charing

2. The clock tower in the [Westminster] Palace yard

3. Westminster Palace [aka the Houses of Parliament, later rebuilt]

4. Westminster Abbey

5. A stone conduit [drinking water piped in from elsewhere]. This is close to where St James Piccadilly church would be built in 1688.

6. St James's Palace, which we saw a minute ago in the 'Cherries' picture.

The street name Piccadilly originated from Pickadilly Hall, an early building on the road, whose owner, tailor Robert Baker, made his fortune selling piccadills in the early 1600s.

"That doesn't help much" - I hear you say - and I can go a bit further and pass on some knowledge which I learned just 10 seconds ago. Piccadills were fashionable collars with scalloped edges and a broad lace or perforated border.

Fashion was a big part of Piccadilly life as can be seen below - a joke - engraved by Benjamin Smith, yet again of the year 1786 when our Benjamin was twelve years old, just around the corner from his house:

The humour lies in the encounter of two 'Street Walkers' at the corner of Piccadilly and Bond Street; one 'Street Walker' is a posh gentleman dandy parading his excessively fashionable and expensive attire along Piccadilly for all to admire; the other 'Street Walker' is a prostitute, a common phenomenon around St James, and particularly in St James's Park.

We are clearly at the junction of Bond Street and Piccadilly, at the point of the blue arrow in the map below. The picture was engraved by Benjamin Smith in 1786, the same year as our Benjamin Partleton attended his sister's wedding 100 yards up the road, so we may assume that street walkers of both types were quite a familiar sight to young Benjamin.

On the subject of fashion, the most famous dandy of all was Beau Brummell, a close contemporary of our Benjamin (though of a different social class, of course), born in 1778, and held to be the most fashionable man in London. Below we see his statue in Jermyn Street, erected in 2002:

Jermyn Street is still, in the present day, an expensive fashion street and specifically famous for bespoke shirts. During 1816, Beau Brummell defaulted on large gambling debts at White's club on St James Street, fell out of favour with the Prince Regent, and fled to France to escape his creditors. It was the greatest possible humiliation to default on these 'debts of honour'. His last entry in White's gambling book was marked 'not paid, 20th January, 1816'. In France he was supported by some of his friends but died penniless and insane from syphilis in Caen in 1840.

Let's get back to Benjamin. He doesn't need to worry about falling out of favour with the Prince Regent because he's never met him.

In 1798, at age 24, it's time for Ben to get married. His bride is Catherine Iremonger:

There is a really startling fact in this record: the witness Benjamin Partleton. Who IS this other Benjamin? Our Benjamin's dad is Thomas Partleton who is our oldest known London Partleton, and whom we know can read and write. The witness Benjamin Partleton is illiterate ('the mark of'). Could this be our Benjamin's granddad, and what is more, a new oldest ancestor? Time, and more research, will tell.

The marriage takes place at the church of St George Hanover Square. This is a new one to us, so we should take a moment to locate it in relation to Benjamin's house:

From the viewpoint of the green arrow in the map, drawn by Thomas Malton in 1787, below we see St George's church with Hanover Square behind it, exactly as Benjamin and Catherine would have seen it on their wedding day.

It's very close to their house on Swallow Street, circled in red, closer even than the church of St James Piccadilly, but we can see the parish boundary as a dotted line running along the north centre-line of Swallow Street and cutting down the south side of Conduit Street:

181 years after Benjamin's marriage, seen from the viewpoint of the purple arrow in the map above, here's Harrison Ford in Little Maddox Street with St George Hanover Square in the background, during the shooting of the movie Hanover Street. Not one of Harrison's more famous films - but what would Benjamin have made of it all?:

Hanover Street was filmed in 1979, but was set in WW2.

To do my research for this page I watched the movie - which has some excellent scenes set in the street - so I get to be film critic as well as historian. It's a love triangle in which Harrison Ford falls for a married English woman [Lesley-Ann Down] and then has to rescue her husband in France. Verdict: a little cheesy but overall it was quite watchable.

There's no tube station at that location on the left in reality, and I thought they had made a really good job of dressing-up Maddox Street and achieved some startling explosions during a bombing by the Luftwaffe. In fact, only by watching the movie all the way through and then watching it again with the director's commentary did I find, much to my surprise, that all the buildings, including that perfect St George Hanover Square church are in fact an elaborate external film set built in 12 weeks at Elstree Studios in the north London suburbs.

Harrison is very familiar with Elstree because it's where he had been to film Star Wars in 1977. And in 1981, he'll be back to Elstree to film Raiders of the Lost Ark and its sequels.

Perhaps I should have realised it wasn't really central London when I watched this scene, and the giant explosion which preceded it? Duh.

Director Peter Hyams explained that he was quite fanatical to achieve authenticity in its wartime look, and the set was carefully reconstructed from actual photos. Armed with this knowledge, I watched some scenes again. It still looked real to me!

But just to prove that nothing in London ever stays the same, not just movie sets, I have pasted together a montage courtesy of Google Street View of the actual road junction now [2009]. The building on the right is brand new. The building on the left is under redevelopment... note that that some of the facade of the building on George Street on the left has been retained as a condition of the planning permission:

Don't forget we are at St George's church for the wedding of Benjamin Partleton and Catherine Iremonger, but while we are here, let's step out from the congregation for a minute and take a stroll down the real Little Maddox Street which we can see in the map below is only about 60 metres long:

Now we are at the corner of Little Maddox Street and Bond Street, No 42 to be precise - exactly at the point of the blue arrow, in the year 1796, as depicted by the comic genius James Gillray, who is, incidentally, buried in the churchyard of St James Piccadilly. If you want to know what people laughed at in the 1790s, just feast your eyes on this - very close to libellous - cartoon!:

There's so much going in in this little masterpiece, it's hard to know where to begin. If 'sandwich-carrots' sounds a bit of a peculiar lunch, it's because the lecherous old goat tugging on the apron of the carrot-seller in the cartoon is purported to be the of the son of John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich. The etching is just brimming with innuendo, from the carrots in the barrow to the hand in the pocket, the look in Sandwich's eye, the comical waistcoat-tails dangling limply out front and even the positioning of the man and the young girl. Sandwich was allegedly in the habit of offering a Guinea (£1 and 1s) to innocent young girls for their favours.

In the window of the bookseller's, which is a real establishment - the Bond Street shop of the prominent bookseller and publisher, Robert Faulder, exactly as it looked on the day of Benjamin's wedding - we see books titled; 'Doe-hunting. An Ode by an Old Buck-Hound'; 'A journey through Life from Maddox Street to Conduit Street and Back Again' among others.

I especially like this engraving because we get a perfect view of the fashions prevalent in the 1790s. Forget the subject matter; this is within a reasonable stretch of how Benjamin and Catherine would be dressed.

We are nearly at the end of our navigation of St George Hanover Square, but here's another picture - a Victorian stereograph from the viewpoint of the orange arrow:

These stereographs were very popular in Victorian times & I'm surprised they have fallen out of favour because I love them. Cross your eyes until the two images merge & you'll see a perfect 3-D image of a street in Victorian London. You could almost step through your computer monitor and have a little walk around.

One last image of st George Hanover Square, from a similar viewpoint of the stereograph, a little further from the church, is seen in the pen and ink sketch below. It was executed by an anonymous artist in 1798 - the exact year when Benjamin and Catherine were married. Who knows, it may have been painted on the very same day. We see a donkey carrying a heavy burden, its rider apparently greeting the figure seated at the kerbside who may be doffing his cap in return.

I really like that picture. It seems we are transported right back in time to the year 1798.

Let's get back to Benjamin's wedding in 1798, the 16th of June, a Saturday. Marriages were usually conducted at the parish church of the bride, who is Catherine Iremonger, but the marriage record states that they are both of the parish of St George, so it's possible that Benjamin was living there for a short while.

But by the following year, they are back at 43 Swallow Street, living with Benjamin's parents - Thomas and Hannah - for the birth of their first child, my ancestor Benjamin Thomas Partleton who was born on 19 June 1799 and christened on 15 July. So it's back to the old font, the same one in which Benjamin himself had been baptised 25 years earlier...

Unfortunately the microfilm copies of St James Parish Registers which are held at Westminster Archives are not very good, as we see below. Thanks to Terry Partleton for making the trip to London and obtaining this image of the baptism:

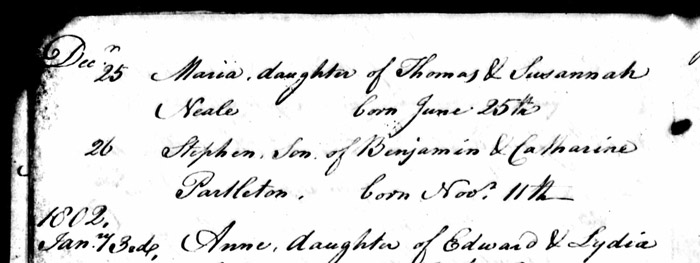

Between 19 June 1799 when the baby was born, and 15 July, when he was christened, an unexpected fact emerges; Benjamin takes out some property insurance:

This information, as PG Wodehouse would have put it, gives us a slight swimming sensation in the head. Benjamin, by all the later evidence, is clearly recorded as a carpenter, or (more often) as a house-painter, and most of his kids certainly grow up to be house-painters. But clearly here, he is insuring a property at 5 Leicester Street - just around the corner from his house at 43 Swallow Street - wherein he is declaring his occupation as chandler.

Below we see both properties highlighted:

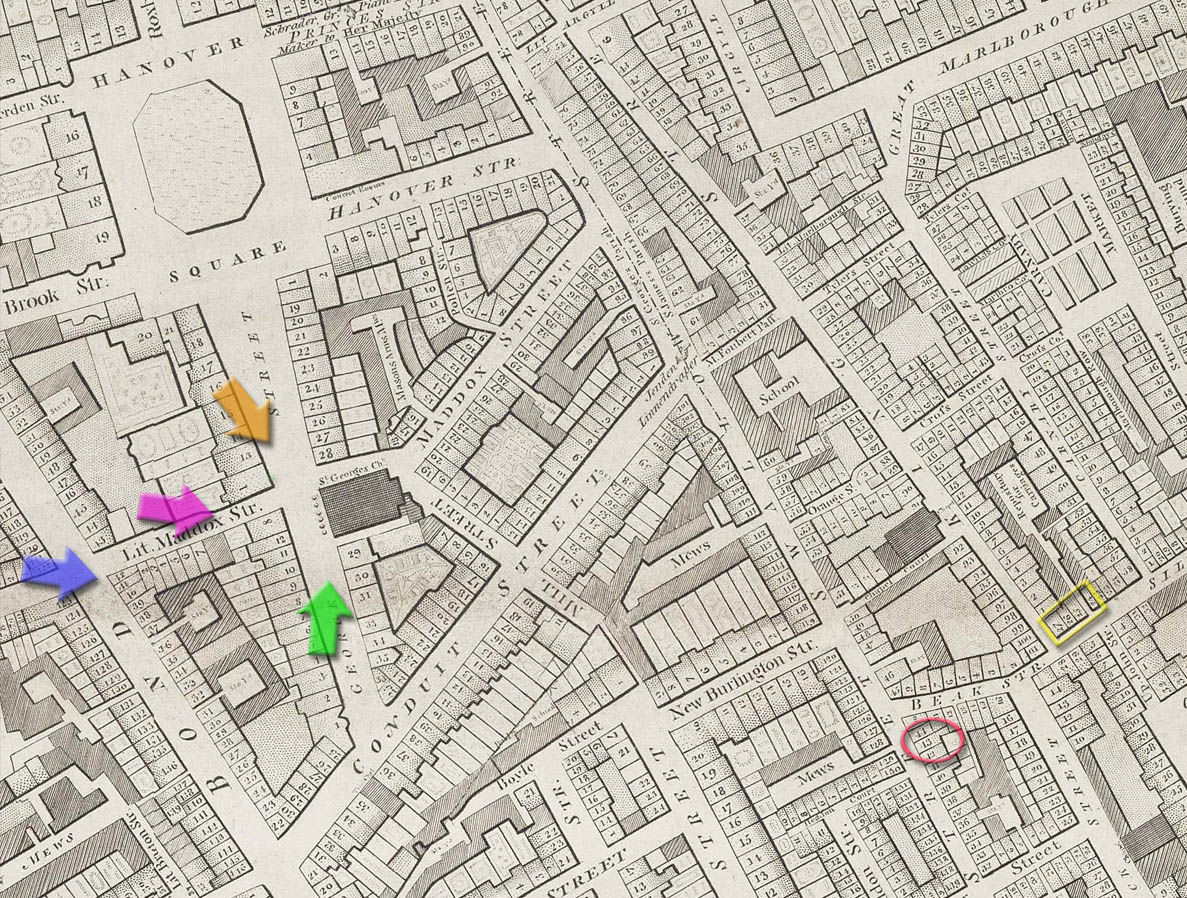

This is wonderful, new information, but there’s just one problem. What’s a chandler?

In search of that answer, specifically seeking a contemporary definition, let’s consult Webster’s Dictionary, 1828 edition and 1913 edition:

Our problem is that the word chandler has several possible meanings. Could it be that Benjamin is running a candle shop, even making them himself? Mmmm… I guess it’s possible.

A modern online dictionary definition may actually help:

I searched the British Library online newspaper archive for all examples of the word chandler for the year 1799. The 16 pages of results were always specific. There were numerous references to tallow-chandlers or wax-chandlers [ie candles], a fair number of corn-chandlers, and a small number of ship’s-chandlers. There were no other types of chandler cited. The corn-chandlers were sometimes vaguely associated with grocers.

Though it’s possible that Benjamin’s dad, Thomas - who was still alive in 1799 - was a mariner, I’m going to rule out the ship’s-chandler possibility. There are no ships on Piccadilly; it’s a business for the quayside. So, it seems that Benjamin has a small retail enterprise. He’s either a grocer/general shopkeeper, or he’s selling candles. I suspect the former. A future trip to the Guildhall Library, where the original insurance document is held, may settle it.

Moving on, in February 1801, Thomas Partleton, Benjamin’s father, died aged about 65-70. It turns out that, in their old age, Benjamin’s mum Hannah and dad Thomas, though they are named as the ratepayers for the family home at Swallow Street, circled red in the map below, are not actually living there. They were residing a few streets away, on Wardour Street, circled blue.

I think it’s reasonable to infer from this that the family is not short of money. Benjamin's dad Thomas Partleton was buried in the neighbouring Westminster parish of St Anne Soho, which means he must have been living on the east side of Wardour Street. From here on, Grandma Hannah Partleton is declared as the ratepayer for the house at Swallow Street though she continues living at Wardour Street.

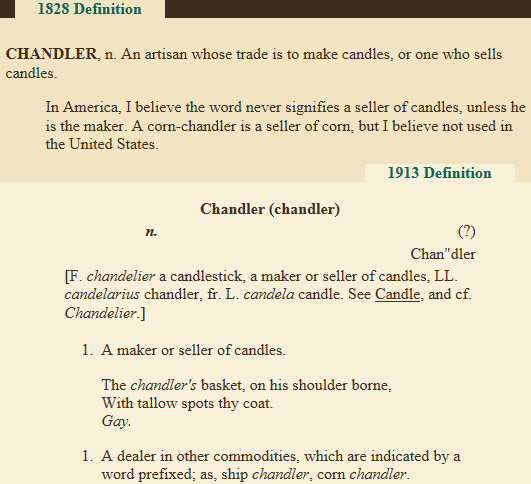

At the end of the same year, 1801, in December, Benjamin and Catherine have their second son baptised; Stephen.

The surprise here is that Stephen was not baptised at St James Westminster, but 11 miles out of London in a Thames-side village called Isleworth.

In the 1819 map we see above, which is Leigh's New Map of the Environs of London, we see Isleworth circled in red, and Piccadilly circled in blue.

"Why are the family in Isleworth?" I hear you ask, and yes, of course you said nothing at all, and I'm at home with the computer in my lap and one eye on the football on TV, so I couldn't possibly hear you even if you did speak. But I'm going to answer anyway...

...actually I'm not going to answer because I don't know why they are in Isleworth. Let's just ignore it, for the time being, and have a look at the village of Isleworth from the viewpoint of the Thames:

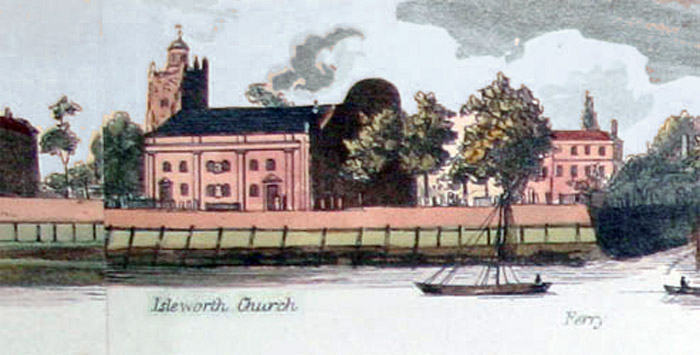

Isleworth in 1801 was very pretty; pastoral, rural, some might say bucolic. It must have been a great place for the family to visit. The church where baby Stephen was baptised - All Saints - can be seen just left of centre.

Three years later, in 1804, Benjamin and Catherine are back home in the parish of St James Westminster where they have another son, Thomas George Partleton, baptised:

So now the family are back in London.

But two years later, 29 June 1806, Benjamin and Catherine are back in Isleworth, where they have their fourth son, James, baptised.

So, now we need to get serious about Isleworth; we can no longer ignore it. Why is the Partleton family there?

To be sure, there are two possible reasons. In the Partleton Tree, in later years, we have occasionally seen the family relocate wholesale to follow a job, but this doesn't feel like that. Why go to Isleworth in 1801, go back to London, and then go back to Isleworth in 1806?

Let's step into Benjamin and Catherine's shoes - some nice sturdy sensible ones, for this is the countryside - and make a trip to Isleworth for the christening in 1806. With them were their sons - Benjamin (my g-g-g-great-grandfather), who was nearly 7, Stephen who was now 5, Thomas 2, and of course the new baby, James, 2 months old. Maybe we will find some clues about the whole Isleworth connection.

Here's the church, All Saints in Isleworth, exactly as Benjamin and Catherine saw it; this was engraved in the year 1807:

Isleworth was a popular subject for artists during this period - no doubt because it is so damn pretty.

The view we see above is the Isleworth section of the Leigh Panorama, a 60-foot-long watercolour aquatint of the whole length of the Thames riverside, published by Samuel Leigh in 1829.

We can see that Isleworth hasn't changed much - except for the cars, and the aeroplane in the sky - by comparing the modern image below, photographed at dusk; we see the lights of the pub, the London Apprentice, and the same building subtitled on Leigh's panorama, and also the pavilion:

xxxxx

xxxxx

Here's Leigh's Panorama advertised in the Bath Chronicle on 29 March 1830:

The price required for the plain version of this lovely publication, £1 8shillings, was over a week's wages for a working man at the time. The hand-coloured edition was nearly three weeks' wages.

Next to the church, there's a ferry...

So, let's hop on the ferry with Benjamin and Catherine and the kids, cross the river, and take a look a the church from the opposite bank of the Thames, as artist John Preston did, nine years later, in 1815:

We can see from the satellite photo below, courtesy of Yahoo Maps, that the artist stood at the point of the yellow arrow, looking towards the church, circled in blue:

From this overhead view we can see, what looks like the opposite bank of the river in Preston's picture, with swans swimming next to it, is in fact an island in the Thames; Isleworth Ait.

While we are on the subject of the ferry, I was reminded by Partleton Tree correspondent Paul Little that famous artist Joseph Mallord William Turner lived in the ferry house from 1804 to 1806 and executed this watercolour painting of it while he lived there:

Since the ferry house is right next to the church, and baby James was christened on 29 June 1806 - which was a Sunday - Paul points out that JMW Turner could have been in the congregation, indeed one would assume that this was quite a likely possibility - except that according to the Turner Society, he left the ferry house in May 1806.

Left: JMW Turner

Left: JMW Turner

Half a mile downstream we can use another contemporary image of Isleworth to envision Benjamin's children playing on the Thames riverbank, and share a little flavour of a 200-year-old family holiday with the Partletons:

The view above, showing the Isleworth landmark building of Syon House, circled red below, was drawn c1815 by artist John Hassell, from the viewpoint of the purple arrow:

So, we have established that Isleworth was very beautiful in 1806. I'd like to have lived there myself. But why was the Partleton family there?

To solve the mystery, we can now turn to Ancestry.co.uk who have recently added the Parish Registers for All Saints church, Isleworth, going back as far as the year 1800. A search reveals the two baptisms we already know about, for Stephen and James Partleton, in 1801 and 1806, but no other Partleton records, baptism, marriage or burial. So, that's a dead end.

But what about Benjamin's Partleton's wife, Catherine Iremonger? We can search the Isleworth Parish Registers for Iremonger. It's a rare name... and as it turns out there is one - just one - and it's in the burials for 03 April 1808, but it's a good one:

You may judge for yourself. The only person named Iremonger featuring in the parish baptism, marriage or burial registers at Isleworth church post-1800 is also called Katharine Iremonger, just like our Catharine. Coincidence? This Katharine Iremonger died aged 60 in 1808 and was buried in the church cemetery. Surely this must be our Catherine's mum.

So it seems in 1801 and 1806 our Catherine took the family home to her mum in Isleworth for the baptism of her baby; indeed she may have gone home to be with her mother for the birth which had taken place two months earlier, in April.

Naturally enough, having found her mum, we should search for Catherine's dad. Unfortunately the burial records for Isleworth at Ancestry.co.uk have only been collated between the years 1800 to 1812, at the moment. If he died before or after these dates, we won't find him. However, the good news is that we have other sources:

The above record was researched by Terry Partleton and shows another rare matching Isleworth record, obtained from Findmypast.co.uk. This time the surname is spelled Ironmonger, but of course we are researching an era when exact spellings really don't signify much. This fellow died in Isleworth in 1824, and what is noticeable is that his first name was Stephen. You may recollect that Catherine's first son was named Benjamin after his father, but her second son - who had been baptised in Isleworth church in 1801 - was also named Stephen.

Stephen is the only match in the Isleworth records for Iremonger or Ironmonger. Is he Catherine's dad? Catherine, if she's about the same age as her husband Benjamin, would be born in about the year 1774 or after. Further supporting evidence is the following marriage record of 1773 for Stephen Ironmonger:

Ok, we've done our best to unravel the mystery of the Isleworth baptisms, and hopefully we have just about closed the case without definitive proof. The supporting facts tie together very tightly. Catherine Iremonger was an Isleworth girl born in the 1770s to parents Stephen Ironmonger and Catherine/Katharine Tranter, and as a young mum had brought some of her babies home for their christenings.

There are no more Partleton baptisms in Isleworth after 1806. The family is back in the Parish of St James in London.

In the following year, 1807, Benjamin would no doubt have been greatly interested in an event which occurred in the parish, in Pall Mall, the street which can be seen in the centre of the map below:

The event in question was Pall Mall becoming the first street in the world to be lit by gas light.

The date was 28 January 1807, and the lights were the talking point of the whole of London.

In the engraving below, drawn by Thomas Rowlandson, celebrating the event, we have another opportunity to see how Benjamin and Catherine would be dressed, and amongst the country-bumpkin, Irish, Quaker and other gags we see yet again a prostitute joke - the lady on the right bemoaning the loss of dark corners with her minder:

The background is sketchy, but in February 2012, Partleton Tree correspondent Theresa Holmes emailed identifying the exact location; Carlton House. Thanks Theresa!

Rowlandson's cartoon was drawn from the viewpoint of the yellow arrow in the map below:

Carlton House was the grand London home of the Prince Regent, which he refurbished and lived in for several decades from 1783. Surrounded by all the gentlemen's clubs, this place was perfect for his playboy lifestyle.

Below we see Carlton House from a similar angle by artist William Westhall after John Hunt, circa 1820s

Carlton House was demolished in 1829, but before we move on, I couldn't match Rowlandson's sketch with that painting::

xxxxxx

xxxxxx

Rowlandson may, of course, have been deploying artistic licence - it's just a sketch after all - but he clearly shows two porticos, which both have arches.

Also visible in the cartoon is the kerbside of Pall Mall - so let's have another look Carlton House from a different angle, drawn in 1788:

Now it becomes clear. What we see in Rowlandson's drawing is not Carlton House, but the grand colonnade which separated it from the street to keep out the hoi-polloi including our Benjamin Partleton. The view above is the one which the public, and Benjamin would have seen, as he grew up in the neighbourhood.

We are looking from the viewpoint of the green arrow in the map below:

If truth be told, the street-lighting was a bit of a stunt. Only a short section of Pall Mall, on one side of the road, between Cockspur Street and Carlton House, was actually lit, and then only occasionally. The purpose of the lighting was a practical demonstration to drum up financial support for a proposed new, ambitious - and potentially very profitable - commercial venture; the National Light and Heat Company.

Here's their advert, touting for investors, just a couple of weeks after the street lights appeared in Pall Mall, in the Hampshire Telegraph of Monday 16 February 1807 :

In 1813, the venture became a reality as commercial gas pipes began to be installed under London's streets.

Let's leave Carlton House and gas lights, and see another view of the neighbourhood, this time from the orange arrow in the map above:

The drawing above is one of William Hogarth's famous Rake's Progress engravings. The rake is on his way to a party held at St James's Palace, which we see at the end of the road - where we bought our cherries a little while ago - and he's about to be arrested by the bailiffs.

The point here is that - though this was drawn many years before Benjamin was born - we see how the streets of the Parish of St James were lit as he grew up: a chap up a ladder refilling the oil street-lamp. He's in the process of carelessly spilling some of the oil on the rake's head.

And here's an early morning look at Pall Mall from the year 1770, four years before Benjamin was born, sans gaslight, from the viewpoint of the blue arrow, and we see what must be oil lamps outside St James's Palace and the building in the foreground:

The view above is from the blue arrow in the map below:

And finally from the other end of Pall Mall, viewpoint of the red arrow, over 200 years after the first gas street lights, we see the modern street lighting on Pall Mall which is clearly a nod of recognition to the original gas lamps.

Oh, and a lovely sunset too. Who doesn't love London?:

One last thing about St James in general and Pall Mall in particular is that it is famous for its posh gentleman's clubs which can be seen teeming in this map of 1862; Boodle's, Brooke's, The Carlton Club, The Reform Club, etc etc etc:

White's, for example, at the north end of St James' Street, where it has been since 1778, was formerly noted for being a big gambling club [one member was Beau Brummell, as we saw earlier], and has included among its members Prince Charles and Prime Minister David Cameron whose daddy was a former chairman of the club. In fact an almost unlimited number of wearisome overprivileged upper-class twits have been members down the years. Cameron resigned in 2008 over White's refusal to admit women - though it took him 15 years to make this decision.

Before we return to Benjamin I will share two stories about White's which I found researching this page... In the 1800s Lord Alvanley bet with a friend £3,000 as to which of two raindrops would first reach the bottom of a pane of the bow window at the front of the club [cf Benjamin Partleton's annual rent of £16 a year]. Alvanley later had to sell off family estates to pay for his ludicrous spending and gambling habits. And in the later 1800s, Henry Eaton was refused membership by White's. He subsequently solved the problem by buying the club for £46,000.

Benjamin's family, who are at this time - at the very most - lower middle class, could not possibly be members of any of these snooty establishments. In June 1808 Benjamin gets a fourth son, William, back again at St James Piccadilly:

December 1808 is the last time Benjamin's mum Hannah is recorded as the ratepayer, which is interesting, because we know for a fact that she was buried on 28 May 1807, so the family are not quite keeping their records straight.

Anyhoo, it's not a big deal. I'm sure Benjamin had his reasons. Of note is that the Watch Rates have gone up from 5d to 6d in the £. That's something we are all familiar with!

Now that both of his parents have died, 33-year-old Benjamin has become the head of the house for 43 Swallow Street, and he is subsequently recorded as the ratepayer.

But this page is becoming way too big. Monopoly may never be the same again, at least for us Brits...

We've seen

![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and

![]() ...

...

Also apparent on the 1799 map of

Benjamin's immediate neighbourhood are ![]() ,

,

![]() , and

, and ![]() ...

...

The smallest

Monopoly street in reality,

and hard to understand how it ever made it on to the board, is tiny

![]() which is a microscopic side-road off Swallow

Street, barely 20 yards long.

which is a microscopic side-road off Swallow

Street, barely 20 yards long.

But one street is looming: if you're from London, you probably know it very well - perhaps you have visited some of its famous shops - Hamley's which claims to be the world's largest toyshop, where I bought my first ever Rubik's Cube; or Liberty's if you have deep pockets to pay for your furniture. It doesn't even exist yet in Benjamin's world - the dice haven't rolled - but when they do, it is to have a massive impact on the Partleton family. It has affected all London Partletons, and the ripples still flow down the years to today... Regent Street!

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

To to continue with Part II of the story of Benjamin

Partleton, click here.

If you enjoyed reading this page, you are invited to 'Like' us on Facebook. Or click on the Twitter button and follow us, and we'll let you know whenever a new page is added to the Partleton Tree:

Do YOU know any more to add to this web page?... or would you like to discuss any of the history... or if you have any observations or comments... all information is always welcome so why not send us an email to partleton@yahoo.co.uk

Click here to return to the Partleton Tree 'In Their Shoes' Page.